The contradiction at the heart of banking

Banks are expected to be safe-keepers and risk-takers at the same time. How is that supposed to work?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the years since the financial crisis, the role banks play in the financial system has come under a lot of scrutiny.

Banking is an industry with a huge contradiction at its core: Depositors want to use banks as a safe place to put their money. But banks are expected to lend that money out, providing capital to businesses and households to make investments, a practice with inherent risks. The less a bank lends, the less it risks its depositors' funds, yet at the same time, the less productive its investments can be.

As banking analyst Frances Coppola notes in Pieria:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

[I]t is plain that people expect banks both to provide security for savings and payments AND provide risk capital for businesses. The apparent impossibility of achieving both of these appears to be lost on politicians who call for banks to make their balance sheets safer (so as not to put deposits, and by extension taxpayers' money, at risk) then criticize them for reducing risk lending. This is fundamentally inconsistent. [Pieria]

In the years before the 2008 financial crisis, banks emphasized lending, leveraging up their balance sheets and taking ever-larger risks, especially in corporate lending, commercial real estate, and residential mortgages. When the crisis hit, these activities put depositors' funds in such jeopardy that the government stepped in to bail out the banking system. In the following years, pressure from regulators, politicians, and customers, coupled with banks' own risk aversion, has led banks to make caution a top priority.

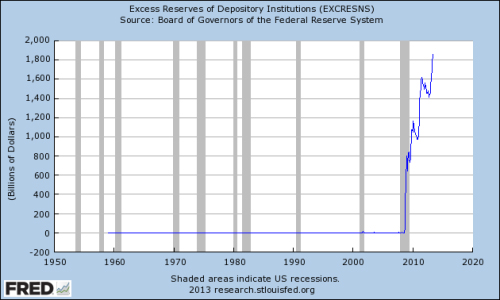

This is illustrated very well by the excess reserves held by banks. Before the crisis, banks used all of their available deposits for lending. Since the crisis, excess reserves have accumulated to such an extent that there are now $1.8 trillion of unused deposits:

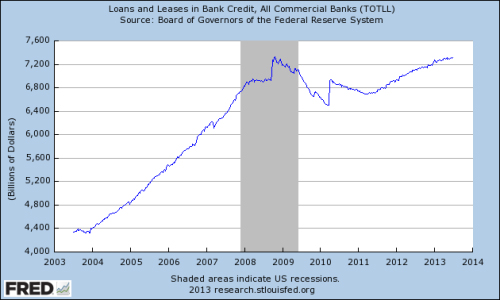

This trend has had a severe impact on lending, which has been in a slump since the financial crisis in 2008:

With lending depressed, the economy has lost a key source of financing. This is likely a significant reason why growth has been quite weak since the crisis — if businesses can't get funding, they can't take on new workers, finance new projects, develop new technologies and systems, etc.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Against this backdrop, the Federal Reserve has tried to stabilize the banking system and increase lending with quantitative easing — the practice of swapping out yielding assets like treasury bonds for cash — to reinforce the banking system and give banks the resources to lend and support business growth.

But almost five years after these programs began, the unemployment rate is still above 7.5 percent, the number of jobs in the economy is still less than it was before the crisis, and current lending is still far below the long-term trend line. The Fed is leading the horse to water, but the horse won't drink. If the banking system doesn't step up to its role as a provider of capital for productive investment, perhaps the government or central bank should cut out the middleman and start lending directly to businesses and individuals at competitive interest rates.

Professor Miles Kimball of the University of Michigan suggested on his blog that Federal Lines of Credit be used a temporary means of getting credit flowing again:

Imagine that the economy is in a recession and the President and Congress are contemplating a tax rebate. What if instead of giving each taxpayer a $200 tax rebate, each taxpayer is mailed a government-issued credit card with a $2,000 line of credit? ($4,000 for a couple.) Even though people would spend a smaller fraction of this line of credit than the 1/3 or so of the tax rebate that they might spend, the fact that the Federal Line of Credit is ten times as big as the tax rebate would have been means it will probably result in a bigger stimulus to the economy. But because taxpayers have to pay back whatever they borrow in their monthly withholding taxes, the cost to the government in the end — and therefore the ultimate addition to the national debt — should be smaller. Since the main thing holding back the size of fiscal stimulus in our current situation has been concerns about adding to the national debt, getting more stimulus per dollar added to the national debt is getting more bang for the buck. [Miles Kimball]

While Kimball's comments are focused upon individuals, a similar program offering larger quantities could work for businesses. And even for individuals and businesses who are already highly indebted and struggling to make payments, such a program would be helpful as it would allow refinancing at a much lower interest rate. These programs could be discontinued when the economy is stronger and banks are more willing to lend.

The banking system performs two roles critical to modern society: allocating capital and providing a secure venue for savings and payments. The continuation of these two functions are a major reason why the banking system was bailed out after the crisis — banks are very much a public utility.

Yet the banking system in its present form struggles to perform these two tasks simultaneously. In the run-up to the crisis, banks engaged in highly risky behavior, lending even to NINJAs — loan applicants with no income, no job, and no assets. And since the crisis, the pendulum has swung the other way entirely. If the banking sector cannot perform its role as a public utility effectively, then there is a strong case that the state should step in to fill the gaps.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.