Why you shouldn't celebrate Egypt's counter-revolution

The military coup undermines democracy. And it marks a return to an authoritarianism that is corrupt and brutal, but at least provides a modicum of stability

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The military bided its time, waiting until President Mohamed Morsi was a big disappointment to his supporters and a bogeyman to the wide swath of Egyptians who now oppose him. And now, just over a year after Morsi was elected, he sits in military detention. Egyptians who voted for Morsi as a counterweight to the military establishment are now cheering his downfall at their hands.

I've spent much of the past year living in Cairo, though I've been a way for the last few days. Nonetheless: Liberal and leftist groups, many of which were initially organized to oppose Hosni Mubarak's military-centered autocracy, have jumped to support the military coup. This contradiction underlines the failure of Morsi's administration and the success the military establishment has had forming alliances with its erstwhile enemies on the left. More than anything else, it illustrates the instability and chaos that characterizes post-revolution politics in Egypt.

Despite the massive popular demonstrations in support of the overthrow and Morsi's clear unpopularity, this latest transition was undeniably a coup.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

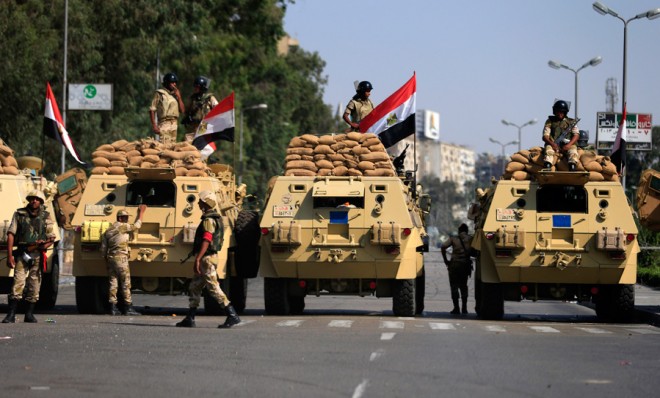

The military has unilaterally dissolved the constitution and quickly rounded up and detained the president and many of his political allies. They have also stopped the broadcast of channels like Al Jazeera, and detained journalists affiliated with these companies.

To replace Morsi, the military elders have installed installed Adli Mansour, the chief justice of the Constitutional Court and a man with a very low profile and virtually no political base. It would be very surprising if he does anything but rubber stamp decisions made by the military.

While the military promises to hold free and fair elections and respect democracy, its actions tells another story, and Egypt seems poised to return to the militaristic, authoritarianism that has defined its politics for so long.

A coup is a tricky thing to support, and the Egyptian military has a long history of oppressive acts and corruption. Still, the fact is that the infant Egyptian democracy wasn't working. The economy is a disaster and the lack of security is terrifying. I know several Egyptians and foreigners who were robbed by armed criminals in the past few months. Brutal gang sexual assaults are disturbingly commons. To make matters worse, rapists and muggers nearly always get away with their crimes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On top of all this, almost everyone is making less money than they were three years ago, and prices for staples and gas are steadily going up.

The situation is undeniably worse than it was before the revolution, and in Cairo most people I've talked to, from impoverished street vendors to Audi-driving rich guys, blame Morsi and his perceived poor management. It is these basic failures, rather than fear of Islamist extremism or Morsi's nascent authoritarianism, that got people in the streets in such overwhelming numbers.

The Egyptians who still support Morsi argue that one year isn't enough time to fix Egypt's huge problems. This is probably true. But the majority of Egyptians don't buy this argument, and increasingly distrust not only Morsi, but also the democratic process that got him into power.

In Egypt, there is no historical precedent for or experience with democracy. Military coups are not demonized, but rather are praised in history books and celebrated with public holidays. Now that democracy is associated with economic desperation and gangs of thugs raping and robbing with impunity, there is an understandable nostalgia for the old days, when the dictatorship kept the tourist money flowing in and did a reasonably good job maintaining security.

While the military is playing lip service to democratic values, it really stands for the opposite: A return to an authoritarianism that was corrupt and brutal, but at least provided a modicum of stability.

While most Egyptians seem to support the military now, this coup was by no means bloodless or universally popular. The large minority of Egyptians who still support President Morsi are terrified and enraged. Islamist supporters are being arrested and shot by security forces and are refusing to accept the new military junta. The sites of major Islamist protests are apparently turning into battlefields with both sides using firearms. Dozens of people have died so far.

When the army last held complete power, immediately after Mubarak's fall, its leaders made it clear they have no compunction about slaughtering large numbers of men, women, and children to keep political opponents quiet. It looks like a year on the back-burner has not tempered this impulse.

While high-ranking members of the Muslim Brotherhood are urging protesters to stay peaceful, there are more radical voices calling for full violent resistance to the coup. Given the violent nature of Egyptian society, the radical stance of many Islamist groups and the unilateral and illegal nature of the military's power grab, increasing violence is virtually guaranteed.

While the failure of Egyptian democracy is troubling, that is not the most disturbing precedent set by the coup. The only thing Mubarak had going for him was that he provided stability, and while the military is loudly taking up this mantle, its leaders are actually pushing Egypt further into chaos and violence.

They have proven that they will not play by the rules. They have proven that one does not earn power through elections, or other official means. In Egypt, one seizes power through disruptive, violent protests, and finally with tanks and kalashnikovs.

The Islamists already are heeding this message, and I have a strong feeling that many of the militant liberal activist groups that now support military intervention out of opposition to Morsi will soon be attacking the military with words, stones, and sawed-off shotguns.

My Egyptian girlfriend and most of my close friends are now praising the military. They are generally liberals who are inclined to distrust both the Muslim Brotherhood and the military. Most of them supported Morsi last year as a bulwark against military power. They are now celebrating his downfall just like most of them celebrated his election just 12 short months ago. We'll see if they stay satisfied.

My Islamist friends are a different story. Some of them are in their homes, mourning in private. Many are already on the streets, protesting, angry, and ready for a fight.

Jake Lippincott earned a degree in Middle Eastern Studies at Hampshire College. He worked in Tunis during the popular uprising there, and is now based in Cairo.