Why do so many domestic terrorists use ricin?

This week's poisoned mailings weren't the first

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

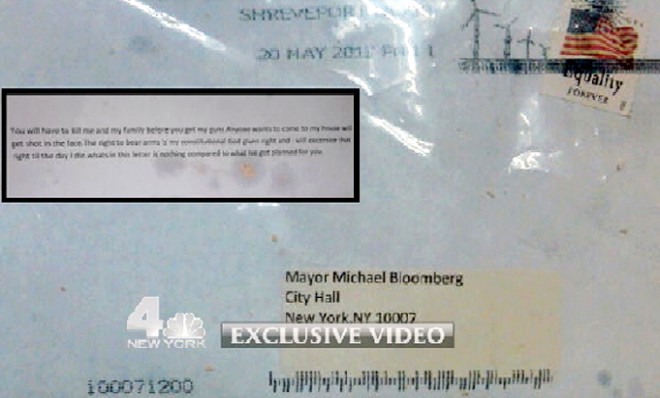

Investigators have identified a Texas man as a person of interest in this week's spate of letters laced with the deadly poison ricin. The mailings this time around were sent to President Obama, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and the office of Bloomberg's gun-control advocacy group. The letters threatened attacks if Obama and Bloomberg continued pushing for tighter gun laws. "What's in this letter is nothing compared to what I've got planned for you," the letters warned.

The letters were the latest in a series of similar poisoning attempts targeting politicians. In 2003, letters containing ricin and signed by "Fallen Angel" — one addressed to the White House — threatened to turn Washington, D.C., "into a ghost town." Another ricin-laced letter arrived in then-Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist's (R-Tenn.) mailroom the following year, and several more were sent in April of this year to Obama and Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.).

Why is ricin the preferred toxin of would-be terrorists? Matt Vasilogambros poses that question at National Journal, and comes up with a simple explanation: "It's because producing ricin is so simple that almost anyone can home-brew it."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There are many recipes online that give step-by-step instructions for how to make ricin into a powdery substance, which would likely be what is put into the letters sent to politicians. Ricin is produced by removing the skin of the castor bean, blending with a nail-polish-type liquid, fermenting, filtering, and drying. In four days, someone can theoretically produce a deadly amount of ricin. [National Journal]

In theory, that makes ricin a potentially lethal weapon for any lone wolf looking to stage a stealthy but headline-grabbing attack. If made well, a dose no bigger than a few grains of table salt can kill a person within a few days. Ricin prevents cells from making proteins, causing cell death and organ failure. There is no test for exposure, and no antidote.

In practice, though, the ricin-laced letters sent in recent years have all been intercepted before reaching their targets, and without killing anyone who handled them (although postal workers who came into contact with the letter addressed to Bloomberg have complained of stomach pains and diarrhea). The reason for the letters' limited impact appears to be that home-cooked ricin paste tends to be of poor quality, note Erika Check Hayden and Meredith Wadman at Nature. "Although minute amounts of ricin can be lethal," they say, "it is difficult to process raw materials into the toxin's most dangerous form, a readily inhaled fine powder."

There's another reason the recent ricin attacks have done little damage. After the 2001 anthrax attacks that killed five people, the U.S. Postal Service and other agencies stepped up efforts to spot tainted mail. They now use sensors to check for ricin, anthrax, and other deadly toxins, which was how the ricin-laced letters addressed to Obama, Wicker, and Bloomberg were detected, according to USA Today. Other measures — such as moving mail rooms off-site, far from politicians' offices, and flagging any suspicious envelope or package — have also helped reduce the danger.

Why bother brewing the stuff, then? "I can't imagine that ricin in an envelope is going to hurt anybody," Raymond Zilinskas, director of chemical and biological weapons non-proliferation at the Monterey Institute of International Studies in California, tells Nature. "It's more likely remnants of a paste, intended to scare people." Scott Gottlieb, a Food and Drug Administration official in the George W. Bush administration, agrees. "At the end of the day, whoever sent this to the president knew it wasn’t going to reach the president," Gottlieb tells National Journal. "This is more of a political statement, in my view."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.