10 smart reads on the Boston Marathon bombing

A collection of the week's smartest, most challenging, and most inspirational journalism about the Boston Marathon bombing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

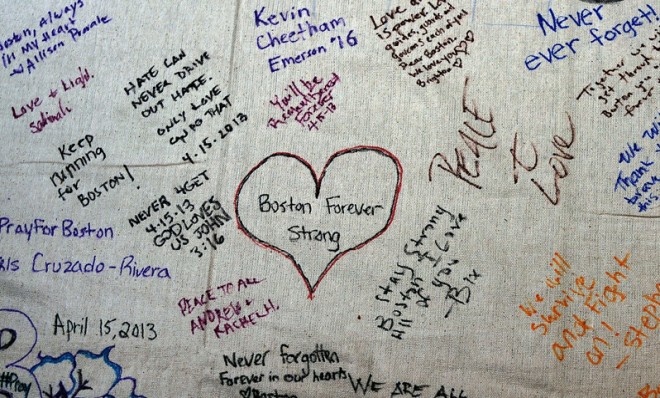

On Monday afternoon, two bombs were detonated at the Boston Marathon, resulting in three fatalities, 183 injuries, and a manhunt that is still ongoing. Throughout the week, dozens of journalists, writers, and commentators have reacted to the Boston Marathon bombing in a variety of ways: Expressing grief, offering inspiration, and asking difficult questions. Here, 10 of the week's smartest pieces on the Boston Marathon bombing:

1. "The Boston Marathon Bombing: Keep Calm and Carry On"

Bruce Schneier, The Atlantic

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

April 15, 2013

As the details about the bombings in Boston unfold, it'd be easy to be scared. It'd be easy to feel powerless and demand that our elected leaders do something — anything — to keep us safe.

It'd be easy, but it'd be wrong. We need to be angry and empathize with the victims without being scared. Our fears would play right into the perpetrators' hands — and magnify the power of their victory for whichever goals whatever group behind this, still to be uncovered, has. We don't have to be scared, and we're not powerless. We actually have all the power here, and there's one thing we can do to render terrorism ineffective: Refuse to be terrorized. [The Atlantic]

Read the rest of the story at The Atlantic.

2. "What the Boston Marathon means to a Bostonian"

Jon Terbush, The Week

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

April 15, 2013

Boston has a long history of racial turmoil, and a reputation — somewhat earned, somewhat exaggerated — as an unwelcoming city deeply segregated along various lines: class, age, race. That someone would bomb Boston on Patriots' Day, a time when the city's disparate groups join together in an outpouring of communion and cheer, is a tragedy. It is the absolute antithesis of everything the day represents.

Patriots' Day was already indelibly linked to past violence and bloodshed. As someone who considers myself a Bostonian no matter where I go and no matter where I live, it pains me to watch that link grow stronger with today's unthinkable crime. [The Week]

Read the rest of the story at The Week.

3. "On Running, Freedom, and the Boston Bombing"

Kathryn Schulz, New York

April 16, 2013

It is silly to say that I love the members of Runner Nation. In my experience, loveableness and unloveableness are evenly distributed across all populations, runners included. And yet, in my more charitable moods, I let myself believe that because running is so intensely individual, it is also, paradoxically, unusually communal: Less jingoistic than team sports, more tolerant, more fundamentally humanist. Some Boston Marathoners ran toward the blast yesterday to help their fellow runners, just as some New York Marathoners turned in their numbers last year even before the race was canceled, choosing to volunteer in the Sandy relief effort instead. Of course, this is more likely evidence for the intermittent generosity of humanity than for any special wonderfulness of runners. But events like the marathon serve to showcase that fine streak in us. They are lovely, temporary citadels of the kindhearted and the hardworking, a land without borders whose sole eligibility test is whether you love to run.

Running is a straightforward act, but the symbolism around it is strangely mixed. On the one hand, it is intimately connected to danger and fear; running is the "flight" half of our fight-or-flight instinct. We run away from threats; we run to save our skin. And yet running is also an enduring metaphor for freedom. We run to freedom, and we run to demonstrate our freedom, and the fact that you will hear this message in variously corny and eloquent and exploitative versions from sources as different as Nike, Fugazi, and the Dixie Chicks makes it no less true. Ask the runners you know if they find running liberating. If they look at you blankly, I'll eat my Asics. [New York]

Read the rest of the story at New York.

Charles P. Pierce, Grantland

April 16, 2013

Nobody loves the Boston Marathon as much as the people who make fun of it year after year. This was the race that previously offered as a prize a not particularly expensive medal, a laurel wreath, and a bowl of beef stew. This was the race that, on one memorable occasion, nobody knew who actually won. I don't know anyone who loved the race that didn't mock it for its monumental inconvenience, its occasionally towering self-regard, and the annual attempts by Boston-area television stations to use it to win another shelf full of local Emmys. This includes me, and I've been around 25 or 30 of them, more or less, in one way or another, watching from the press truck, from the firehouse in Newton, from somebody's roof, and very often from just barely inside the front door of the late, lamented Eliot Lounge. The Marathon was the old, drunk uncle of Boston sports, the last of the true festival events. Every other one of our major sporting rodeos is locked down, and tightened up, and Fail-Safed until the Super Bowl now is little more than NORAD with bad rock music and offensive tackles. You can't do that to the Marathon. There was no way to do it. There was no way to lock down, or tighten up, or Fail-Safe into Security Theater a race that covers 26.2 miles, a race that travels from town to town, a race that travels past people's houses. There was no way to garrison the Boston Marathon. Now there will be. Someone will find a way to do it. And I do not know what the race will be now. I literally haven't the vaguest clue. [Grantland]

Read the rest of the story at Grantland.

5. "The Morning After: A Sea of Yellow Bags"

Ian Crouch, The New Yorker

April 16, 2013

Last evening, there was news of runners moving along the Charles River, casting their bouncing shadows along the paths. A sports city, and a runner's city, stuck to old routines — now perhaps out of pride as much as muscle memory. This morning, a familiar figure passed my window: A short fireplug of a man making his daily way up the street, at his usual time, shuffling at his always dogged and purposeful pace.

A few hours later, the marathon's staff and volunteers were handing people their bags. They also gave out medals. Some people bowed their heads to receive them around their necks in a ceremonial fashion. There was some applause. Others declined the ritual, and quickly put the medals away. [The New Yorker]

Read the rest of the story at The New Yorker.

6. "The People Who Watch Marathons"

Erin Gloria Ryan, Jezebel

April 16, 2013

It's even common (albeit debatedly cheesy) for marathoners to iron their first names onto their raceday shirts. This isn't so their wasted bodies are easily identifiable in the medical tent when they've run so hard they can no longer speak (that's what race bibs are for). It's so marathon spectators know how to encourage them accurately. When I ran the Chicago marathon in 2010, I didn't iron on my name, but that didn't keep this group of people who had roused themselves from bed and skipped brunch to watch 40,000 carb loaded runners stagger for 26.2 miles from yelling words of encouragement to me, a stranger, on that 80-degree day. "Come on, pink shirt!" "Pink tank top way to be! You're almost there!" Some yelled the number on my bib. Then, after I'd pass, they'd cheer for the next runner to approach that they'd never met.There's a woman who used to hand out homemade Jello shots to runners at mile 23 along the Chicago course, which sounds gross, but actually turns out to be the perfect combination of cool carbohydrates and enough alcohol to take the edge off the tiniest bit. In Boystown, burly men twirl prop guns on a stage off Broadway, and in Pilsen, a mariachi band plays while ballet folklórico dancers twirl. Spectators even spread out along the lonely stretch between miles 18 and 21, standing in the sun with signs far from any train stations. All for people they've probably never seen, and will probably never see again. [Jezebel]

Read the rest of the story at Jezebel.

7. "Messing with the Wrong City"

Dennis Lehane, The New York Times

April 16, 2013

I do love this city. I love its atrocious accent, its inferiority complex in terms of New York, its nut-job drivers, the insane logic of its street system. I get a perverse pleasure every time I take the T in the winter and the air-conditioning is on in the subway car, or when I take it in the summer and the heat is blasting. Bostonians don't love easy things, they love hard things — blizzards, the bleachers in Fenway Park, a good brawl over a contested parking space. Two different friends texted me the identical message yesterday: They messed with the wrong city. This wasn't a macho sentiment. It wasn't "Bring it on" or a similarly insipid bit of posturing. The point wasn't how we were going to mass in the coffee shops of the South End to figure out how to retaliate. Law enforcement will take care of that, thank you. No, what a Bostonian means when he or she says "They messed with the wrong city" is "You don't think this changes anything, do you?"

Trust me, we won't be giving up any civil liberties to keep ourselves safe because of this. We won't cancel next year's marathon. We won't drive to New Hampshire and stockpile weapons. When the authorities find the weak and terminally maladjusted culprit or culprits, we'll roll our eyes at whatever backward ideology they embrace and move on with our lives. [New York Times]

Read the rest of the story at The New York Times.

Amy Davidson, The New Yorker

April 17, 2013

A twenty-year-old man who had been watching the Boston Marathon had his body torn into by the force of a bomb. He wasn't alone; a hundred and seventy-six people were injured and three were killed. But he was the only one who, while in the hospital being treated for his wounds, had his apartment searched in "a startling show of force," as his fellow-tenants described it to the Bost Herald, with a "phalanx" of officers and agents and two K9 units. He was the one whose belongings were carried out in paper bags as his neighbors watched; whose roommate, also a student, was questioned for five hours ("I was scared") before coming out to say that he didn't think his friend was someone who'd plant a bomb — that he was a nice guy who liked sports. "Let me go to school, dude," the roommate said later in the day, covering his face with his hands and almost crying, as a Fox News producer followed him and asked him, again and again, if he was sure he hadn't been living with a killer.

Why the search, the interrogation, the dogs, the bomb squad, and the injured man's name tweeted out, attached to the word "suspect"? After the bombs went off, people were running in every direction—so was the young man. Many, like him, were hurt badly; many of them were saved by the unflinching kindness of strangers, who carried them or stopped the bleeding with their own hands and improvised tourniquets. "Exhausted runners who kept running to the nearest hospital to give blood," President Obama said. "They helped one another, consoled one another," Carmen Ortiz, the U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, said. In the midst of that, according to a CBS News report, a bystander saw the young man running, badly hurt, rushed to him, and then "tackled" him, bringing him down. People thought he looked suspicious. [The New Yorker]

Read the rest of the story at The New Yorker.

9. "How Bombs in Iraq Saved Lives in Boston"

Tim Murphy, Mother Jones

April 18, 2013

Hospitals in Boston adopted a basic tactic from Iraq to eliminate any unnecessary confusion as to which patients needed which kind of care. As the Times explained, surgeons "used felt markers to write patients' vital signs and injuries on their chests — safely away from the leg wounds — so that if a patient's chart was misplaced during a transfer to surgery or intensive care, for example, there would be no question about what was found in the emergency room." But the largest benefit of the war experience may have been training.

"Learning how to care for these wounds, how much work has to be done, how much tissue you need to remove, how much to leave behind — that's something that is almost impossible to recreate in a civilian training environment," Jenkins says. "We all learned to do this when we went to the war. And those of us who learned early passed it on, literally, surgeon to surgeon, as they exchanged positions in the war. A new surgeon replacement would arrive and you'd have three days to go over with them and you'd practice side-by-side and show them, this is how you do this. [Mother Jones]

Read the rest of the story at Mother Jones.

10. "For Boston, a time to heal"

Kevin Paul Dupon, The Boston Globe

April 19, 2013

There is no easy, quick cure for a city's fractured soul. There are only first steps toward familiarity, the awkward and hesitant inching toward a renewed normalcy, a reclaimed sense of safety, security, home. With sorrow, terror, and a festering defiance tugging at our town, TD Garden swung open its doors Wednesday night to the Bruins and Sabres, the first massive public gathering in Boston since Monday's horrific, murderous bombings at the Boston Marathon finish line.

It was a night to remember, a hope to hold dear, only some 48 hours after the afternoon we all wish could be chased from memory.

"You try and live your life in peace," said Bruins coach Claude Julien, summing up what so many of us are thinking, "and there's people that are trying to disrupt that. And the people that are trying to live their life in peace are all going to stick together. And that's what we have here." [Boston Globe]

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.