The 65-year battle over the Deceased Wife's Sister's Marriage Act

Opponents of the bill saw it as a slippery slope that would lead to the legalization of all kinds of incest

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Until 1907, it was illegal in England for a man to marry the sister of his dead wife. That kind of marriage had been made explicitly illegal in 1835 when Parliament passed a bill designed to protect the inheritance of the son of a Duke who had married his dead wife's sister. In-laws had been marrying each other for a long time, but those marriages were considered "voidable," if anyone wanted to challenge them. The 1835 bill said that that the marriages that had already happened could no longer be voided (the Duke's son would get his due!), but from then on, no more marrying your dead wife's sister.

Parliament had to tack that part on to get the bill to pass. In the social climate of the time it was "too soon" to eliminate the taboo on in-law marriage in one fell swoop. When the more progressive bill to legalize wife's sister marriage was finally introduced in 1842, a fight broke out that would last 65 years.

What was the big deal? Opponents of the bill saw it as a slippery slope that would lead to the legalization of all kinds of incest. They drew arguments from the Bible: Genesis 2 states that husband and wife "became one flesh," therefore your wife's sister was really your own sister. Leviticus prohibits a man from uncovering "the nakedness of thy brother's wife," and so, by analogy, he shouldn't do it to his wife's sister either. Arguments from science included the bizarre claim that married couples become blood relations through some biological consequence of sexual intercourse, or that the idea that in-law marriage was wrong came from evolutionary instinct. People also thought it would destroy the family by encouraging husbands and their wives' sisters to lust after each other while the wives were still alive.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

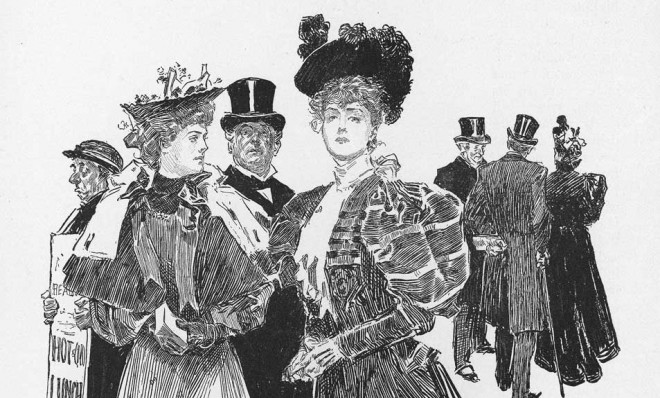

Were there really so many brothers- and sisters-in-law who wanted to get married? Not really, but it was more common than it is now. Women often died in childbirth, and their unmarried sisters, who had few other options to support themselves besides marriage, would step in to care for the family. For convenience, and sometimes developing love, remarriage seemed like the thing to do. Supporters of the act argued that prohibiting these marriages was unfair to the poor, who could not afford to hire help and could not travel out of the country to get married, as the upper class often did to get around the law.

The Deceased Wife's Sister's Marriage Act finally passed in 1907. By that time, the prohibition had long been lifted in most of Europe, the United States and the colonies. At the same time, society was changing in a way that meant fewer women were dying in childbirth and single women had more opportunities to support themselves. Not as many people wanted to make this kind of marriage. But if they did, they finally had freedom to choose it. After registering a few sputtering complaints, opponents of the bill got used to it too, and the world continued to spin.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Arika Okrent is editor-at-large at TheWeek.com and a frequent contributor to Mental Floss. She is the author of In the Land of Invented Languages, a history of the attempt to build a better language. She holds a doctorate in linguistics and a first-level certification in Klingon. Follow her on Twitter.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day