The long-lost continent hidden underneath the Indian Ocean

Researchers believe they've finally found proof of a prehistoric microcontinent called Mauritia

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

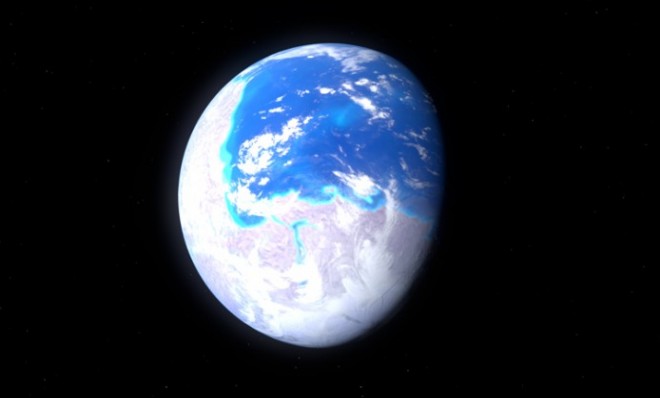

Some 85 million years ago, a small landmass was sandwiched somewhere between what are now India and Madagascar. This ancient continent — Mauritia — was long the stuff of near legend, with geologists not totally sure if it ever even existed. But now, new evidence suggests that the long-lost prehistoric continent is actually buried — in pieces — underneath the waves of the Indian Ocean.

The world was a very different place back when Mauritia was around. Remember, until just 750 million years ago, our planet's landmasses were all joined in a supercontinent called Rodinia. But Rodinia was eventually busted up, and millions of years of volcanic eruptions and plate tectonics eventually cleaved thousands of miles between India and Madagascar, leaving Mauritia surrounded by ocean. Then, starting around 85 million years ago, the small desolate landmass broke apart and vanished.

In a new study published in the journal Nature Geoscience, researchers from Norway, Germany, and Britain claim to have discovered a "hidden" ancient crust buried under certain parts of the Indian Ocean. This hidden crust has been obscured by younger, "fresh" lava from underwater volcanic activity, and in some places, exhibited slightly stronger gravitational fields. This could have been due to a natural thickening of the Earth's crust caused by magma, but scientists had a hunch it was something else.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Using a computer model, researchers traced back the movements of tectonic plates to pinpoint where these areas of intense gravity were located 50 million to 100 million years ago. Sure enough, the puzzle pieces were once attached to the western edge of India — where Mauritia was assumed to sit.

To test their findings, researchers took sand samples from several beaches in modern-day Mauritius, a small island nation a few hundred miles east of Madagascar that researchers think was once connected to the continent Mauritia. Once again, they found something strange: Zircons, a mineral associated with continental crust, were shown to be hundreds of millions years old; the island's crust itself, in contrast, was just 10 million years old — a baby by comparison.

According to ScienceNOW, the researchers, led by geophysicist Trond H. Torsvik of the University of Oslo, think the zircons got there when a volcano long ago "punched its way through pieces of pre-existing continental crust on the seafloor," spreading the prehistoric minerals all over the modern beach. That means buried underneath the seawater and sea-crusts may be the ancient microcontinent of Mauritia.

Of course, the results are far from conclusive. But Torsvik and his team are optimistic about what these initial findings suggest. "We need seismic data which can image the structure... this would be the ultimate proof [of Mauritia's existence]" Torsvik tells the BBC. "Or you can drill deep, but that would cost a lot of money."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com