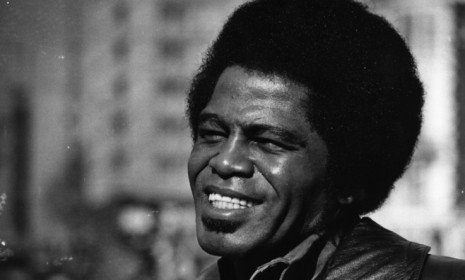

Did James Brown save Boston?

Martin Luther King was dead and cities were burning, says RJ Smith, but the soul singer turned down the heat

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A VIDEO CLIP of Martin Luther King Jr. and James Brown, standing together in front of the Miami Hilton: King on a step by the hotel entrance, Brown on the sidewalk. Wearing a suit and tie, King drapes his arm around the singer's shoulder, his manner projecting a mellow geniality. He is drawing Brown in.

But Brown does not wish to be included. He has a leather overcoat on; he is all but scowling beside King. The reverend wants to keep talking, but the singer moves away quickly, stops in his tracks, then gets behind the wheel of a big car. He throws the camera a forced smile and then drives off.

These two icons knew one another, but they came from radically different places. There were vast cultural differences, rooted in family, education, and economic background. "We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality," King believed. Brown was not so sure. Instinctively the singer responded to obstacles in his path with a display of money and aggression. The idea of a mass movement, of an appeal based on shared beliefs rather than on superior individuality, was not in Brown's makeup. Folks could not be trusted.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"He talked sometimes about King, but not obsessively," said the Reverend Al Sharpton. "He was in one world and lived in it. He respected Dr. King, and knew that King had given his life. But he did not believe in nonviolence, he always told me. And he felt that Dr. King was not the grassroots guy he was. He respected him, he just didn't see Dr. King as him."

In the beginning of April 1968, Brown and his band had returned from their first trip to Africa, having spent two days in Ivory Coast. In New York, they were getting ready to hit the road when reports came that King had been shot in Memphis. As the nation mourned, they were supposed to play a big show, their biggest yet in Boston, the next day.

IN THE LATE 1960s, the threat of mass racial violence extended beneath the surface of daily life. "I am afraid of what lies ahead of us," King said. "We could end up with a full-scale race war in this country." The previous summer there were riots in Detroit, Newark, Tampa, Buffalo, and elsewhere. In Orangeburg, S.C., in February 1968, 28 African-Americans were injured and three killed by police trying to break up a demonstration to integrate a bowling alley. Now it was summer again, and the most important figure in the civil-rights movement had just been murdered.

The singer was chatting about his African trip on a New York talk show when the broadcast was interrupted by a bulletin that the minister had been shot. Within hours of King's death on April 4, 1968, Brown was giving statements to black radio stations, urging listeners not to express their anger by burning down their neighborhoods. Then he pondered the Boston performance. A show had long been booked, but reports of fires and mayhem were streaming in from all around the country. The rage beneath the floorboards was out in the open, and the only question that mattered for politicians and performers alike in the days ahead was how their small gestures might shape larger ones.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Unbeknownst to Brown, the managers of Boston Garden had already planned on canceling his show, operating on the belief that canceling all public events was safer and would keep people off the streets. The event's promoter and a black city councilman warned Mayor Kevin White that this was a terrible idea, bringing thousands of young African-Americans into the heart of downtown and then leaving them there disappointed and angrier than before. How to handle the booking and the crowd with the looming threat of violence was a problem. But even before that was a more immediate question: Who was going to explain to the mayor of Boston who James Brown was?

That's one marker of how segregated the city was: James Brown was probably the most famous black performer in America — a legend who could fill the biggest venue in town — and the leading white official, Kevin White, had no reason to even know his name.

It was decided that the concert should go forward once the mayor was told how many ticketholders were likely to be downtown, and that any cancellation would be interpreted as pre-emptively punishing blacks. Then it was decided at City Hall that the show should be broadcast live on local television, thus giving Bostonians a focus for their grief, and a reason to stay home.

But a crisis loomed over how to pay Brown for the show. Because if the artist in him felt a responsibility to honor King and to do what he could to avoid bloodshed, the businessman felt a need to see payment for services rendered. The city had just cost him a lot of money, what with the Garden seating 14,000; that was 14,000 tickets Brown hoped to sell, and now the mayor was giving fans a way to see the show for free on TV.

It was ignoble of Brown not to do the show for free. But it's possible to comprehend Brown's perspective, too. Kevin White kept calling him "Jim," pressuring him, telling Brown he owed it to Boston to stick his neck out further than he was willing to. In the end, over a barrel, the city agreed to Brown's $60,000 fee. Then, when the show was over, the city reneged on the agreement, giving him, according to Charles Bobbit, Brown's most trusted adviser, just $10,000. "Where the rest of the money went, we'll never know," said Bobbit.

BROWN HAD BIGGER worries. There were some African-Americans who would attack him as an Uncle Tom for urging his people to sit down instead of protesting King's death, as Brown had figured out before the night began. Should there be violence, now that he was cast as peacemaker, he would receive some of the blame. Did he not implore enough, or did the music stir folks up? He understood how carefully he had to choose his words and gestures.

Driving in the bus to the Garden, band member Fred Wesley said he was worried he might be shot en route or on stage. Some in the group were praying to just get through things; others were ready to run. Ultimately, they all went into the deepest show-must-go-on trance.

At the beginning of the event, Brown says the hardest words there would be to say all night. "We got to pay our respects to the late, great, incomparable — somebody we love very much, and I have all the admiration in the world for…I got a chance to know him personally — the late, great Dr. Martin Luther King."

Brown brings Mayor White out; he is blinking, groping for air. Like Fred Wesley, he too thought perhaps he could die this night. Brown reads the moment and rushes in, conferring on the white politico his personal stamp, saying, "Just let me say, I had the pleasure of meetin' him and I said, 'Honorable Mayor,' and he said, 'Look man, just call me Kevin.' And look, this is a swingin' cat. Okay, yeah, give him a big round of applause, ladies and gentlemen. He's a swinging cat." The words were perfect in the moment, Brown establishing authority for himself and for the mayor at the same time.

"The man is together!" raved Brown.

This was nonviolent crowd control, and the master of moving audiences had to take things to a new level. There were perhaps only 2,000 people in the Garden, but Brown spoke directly to them, and adeptly measured the folks watching at home, too. Boston was where all those nights on the chitlin' circuit — learning how to feel what the house desired, how to make thousands rise up and subdue crowds buggin' for a brawl — had brought him to.

Boston police officers formed a line along the sides of the stage. Then came the most emotionally charged moment of the show, the "cape act," in which Brown performs "Please, Please, Please," a powerful bit of stagecraft in which he goes down on his knees again and again, resembling nothing so much as a shaman going through a ritual of death and resurrection. A group of young fans start pushing past white officers on stage. Bodies rushed in from both sides.

Down on one knee, Brown called for "I Can't Stand Myself (When You Touch Me)," and one, three, five youths broke through and jumped up, grabbing the singer. The police forced them back, and suddenly, here was the worst possibility, white cops aggressively confronting black youths on live TV.

The band went stone cold silent, the house lights went up. "Let me finish the show," Brown pleaded. "We're all black. Let's respect ourselves. Are we together or are we ain't?"

It worked. "We are," the audience yelled back. He signals the drummer — "hit the thing, man!" — and he is back in business. The show continued, and there was no violence in downtown Boston that night.

THE BOSTON GARDEN show has become a major chapter in the telling of Brown's life, and was an even bigger chapter when Brown described it. "I was able to speak to the country during the crisis after the assassination of Dr. King," he said, "and they followed my advice and that was one of the things that meant most to me."

One problem with this formulation is that, in the absence of a riot, it is hard to prove that any one or 100 events kept it from happening. In the days after the murder, some 125 American cities experienced upheavals, leaving 46 dead and 2,600 injured. Boston did not, but it's impossible to prove a negative. No riot started, but did James Brown stop one?

Indisputably, he kept thousands of angry citizens off the streets that night. News accounts in the days following gave Brown great credit for keeping the peace, and a legend was born. No doubt he recognized Dr. King's inability to quell rioting in Watts in 1965, or to control violence during the Memphis garbage workers strike in May 1968. King could not stop a riot, but James Brown could.

He did it because, he would say later, he loved his country and didn't want to see bad things happen. He did it because he loved his people, and thought King's death marked a moment to push forth with his mission, not to ruin it with violence that would be crushed. Though he was hardly a believer in nonviolence, Brown performed the Boston show with King's words in mind. He had sized King up as a sincere man, somebody who believed in what he was saying, and Brown had a Southerner's respect for someone who went the distance for what he believed in. Brown performed that night out of a sense of honor, because it would be wrong to not honor an honest man's memory.

Brown's willingness to stick his neck out earned him notice within the White House. In May he was invited to a Washington state dinner for the prime minister of Thailand. When he took his seat, the singer found a note at the table: "Thanks much for what you are doing for your country, Lyndon Johnson."

From The One, by RJ Smith, published by Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. ©2012 by RJ Smith, reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.