Space worms: The key to human survival on Mars?

A normally Earthbound wriggler could become the interstellar version of a canary in a coal mine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The fate of mankind's future in space may hinge on microscopic worms. The tiny creatures, known as Caenorhabditis elegans, were recently blasted into space on the shuttle Discovery and studied aboard the International Space Station by British scientists. The results of the research were published this week in the Royal Society journal, and yield clues about humans' ability to colonize other planets. Here's what you should know:

What do we need these worms for?

They'll be guinea pigs, essentially. Regular space travel is "no easy amble," says Jennifer Carpenter at BBC News. "Humans must first learn to cheaply and safely propel themselves into space," where the body is subjected to high levels of radiation and anti-gravity. "Without the gravitational pull of Earth," important muscles — including the heart — can deteriorate. Enter the space worms.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How were these worms studied?

C. elegan shares half of its genes with humans, says Jennifer Viegas at Discovery, making the worms ideal test subjects. In this study, 4,000 of the worms were left alone for six months in space, "with no one even touching the organisms." Even though life aboard the space station has one tenth the gravity of Earth and receives 10 times the radiation exposure, the worms were able to do "just fine," spawning 12 generations of offspring.

What does this mean for us?

Scientists want to send worm colonies into deep space for long periods of time, beaming data back to Earth to determine if a region is potentially habitable by humans. "We would love to send worms to places like Mars and/or other planets," says the study's co-author, Nathaniel Szewczyk. "The key challenge, and a major goal of this publication, is to convince governments and/or funding agencies that this can and should be done."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

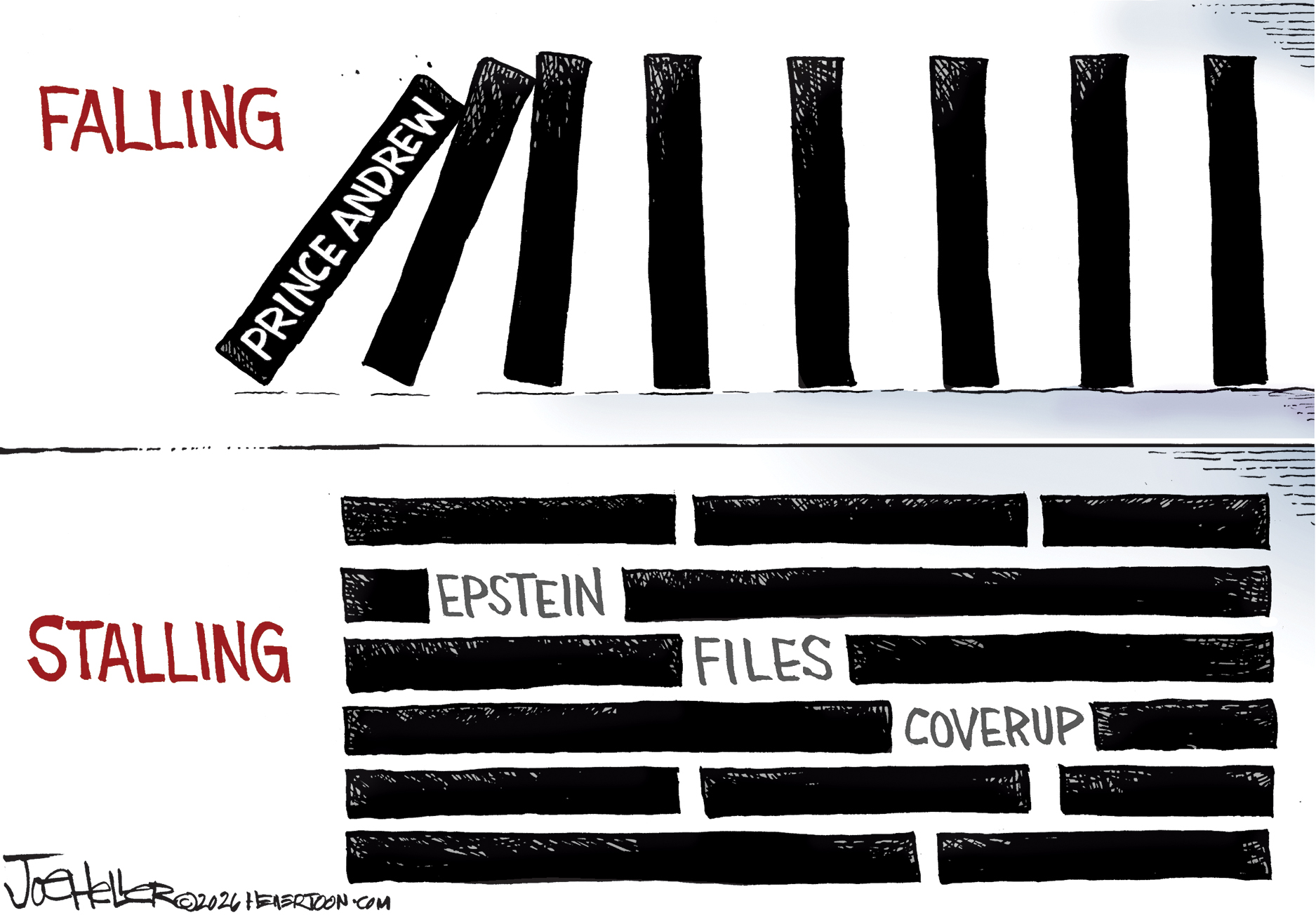

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon