Exhibit of the week: Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia

The renovated wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Islamic gallery displays 1,200 works and spans 13 centuries, from the birth of Islam through the 1920s.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

Permanent collection

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“Just when we needed to learn everything we could about Islamic culture, a crucial teaching tool disappeared,” said Holland Cotter in The New York Times. Eight years ago, when memories of 9/11 were still raw, “one of the world’s premier collections of Islamic art” vanished into storage as the Met undertook a $40 million renovation of its “Islamic Art” galleries. Finally, though, the museum has reopened that wing, unveiling an expanded installation that’s “as intelligent as it is visually resplendent.” The 1,200 works on display span 13 centuries, from the birth of Islam through the 1920s, and if your eyes are open to them, they’ll “set you traveling.” In fact, that seems to be the curators’ point. This is the art not of “a religiously driven monoculture” but of many lands and many interacting secular and religious traditions. “Over and over again, we’re reminded how fluid a concept Islamic art can be, and often is.”

The new galleries tell “a powerful story,” said Lee Lawrence in The Wall Street Journal. The influence of Islam on art began in calligraphy and in the art of the book. So the first galleries showcase “lavishly illustrated Korans, as well as the palpable passion with which calligraphers developed and refined writing styles.” The prominence of the written word, in turn, carried over into other art forms, even as various human and animal images began dancing across the region’s textiles, paintings, porcelains, and carpets. Religion is revealed to be only one of the forces guiding the emerging aesthetic. Trade was “an equally powerful force,” inspiring Arab potters, for instance, to riff on China’s “rising phoenixes, swimming fish, and writhing dragons,” both before and after the Mongol invasions.

Countless of the objects here are so gorgeous that they “gave me palpitations,” said Jerry Saltz in New York. In a Syrian watercolor from 1315, a towering contraption atop a striding elephant is home to two men, a whistling bird, and a red dragon whose collective activities provide a metaphor for the workings of the universe. “On one piece of paper,” a viewer gets “beauty that goes off the charts, and imagination that goes off the rails.” The Met seems to understand how well such work speaks for itself; many of the rooms of this renovated wing “are unspecial to look at, but they make looking at art special.” Better yet, the sheer fecundity of the work teaches us that “the world is a republic of ideas,” not a battle among monocultures. “Culture is not competition. Culture is convergence.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

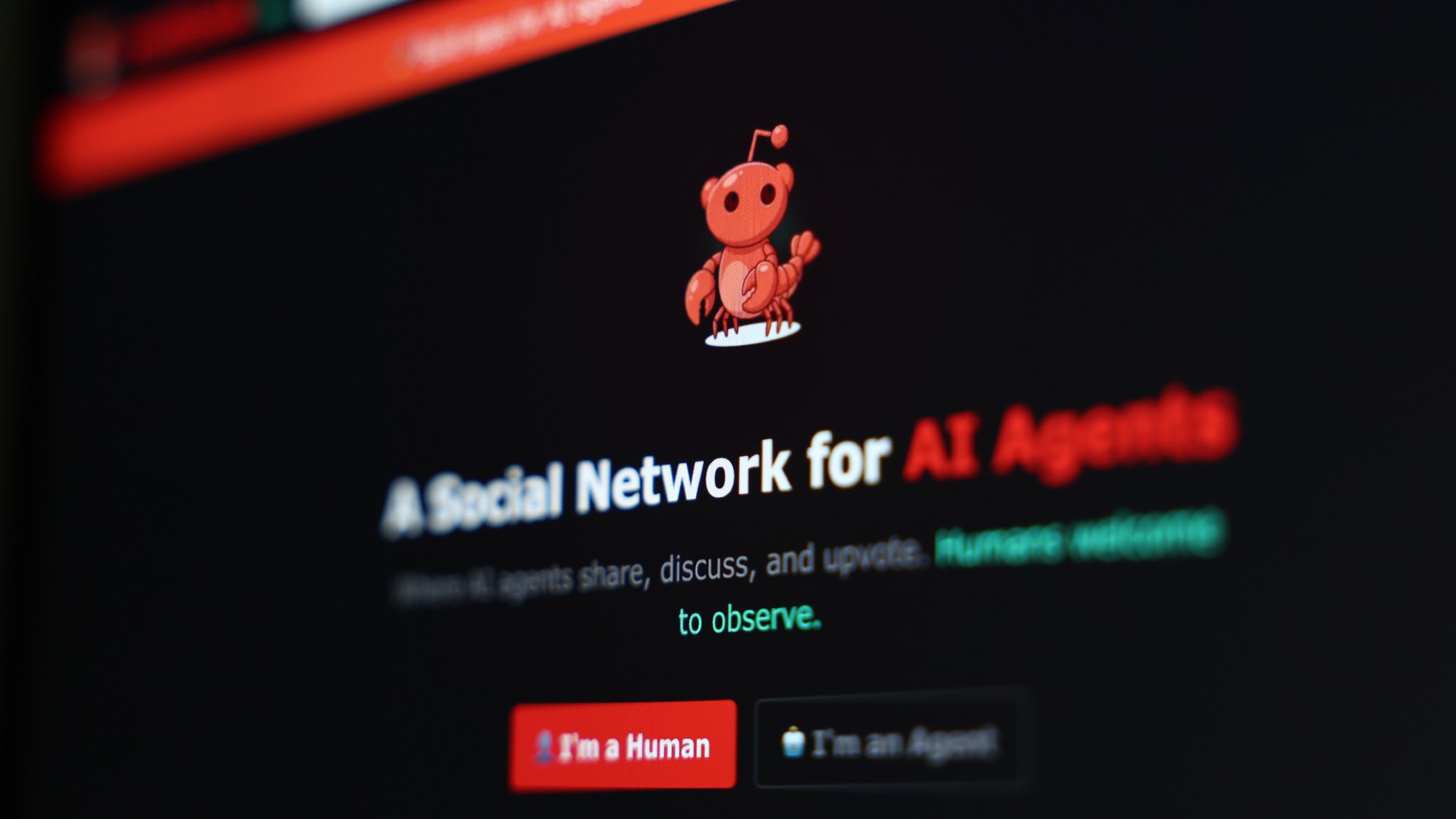

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg