The pope and the Nazis

Charges that Pope Pius XII did not resist the Holocaust are complicating his candidacy for sainthood.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Should Pius XII be a saint?

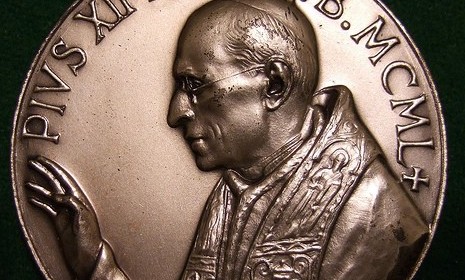

Pope Benedict XVI thinks so. Last month, he designated Pius “Venerable,” putting him on track to beatification and, ultimately, canonization. Benedict signed a decree of “heroic virtue” attesting to Pius’ “saintly” life, but some scholars believe Benedict’s admiration for his predecessor is based on their mutual theological conservatism. Like Benedict, Pius stressed the primacy of papal authority and traditional teachings. “Pius is really his pope,” says one Vatican insider, noting that Pius reigned when Benedict was coming of age. Pius’ candidacy for sainthood actually has been pending for years—his nomination process began in 1965—and Benedict may feel that unless it moves forward, it will languish forever. But whatever Benedict’s motives, critics say that Pius doesn’t warrant sainthood, arguing that he ignored the great moral imperative of his time: saving European Jewry during World War II.

What’s the evidence against him?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The critics’ case begins when Pius, who served as pope from 1939 to 1958, was still Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, secretary of state for the Vatican. In 1933, he negotiated the Reichskonkordat, the first international treaty recognizing Hitler’s regime. Under its terms, the rights of the German Catholic Church were guaranteed; in return, the church agreed to “honor” the Nazis’ civil authority in Germany. The Vatican had been signing similar concordats since before the French Revolution. But Hitler crowed that Pius’ agreement, which helped give his new government legitimacy, was “especially significant in the urgent struggle against international Jewry.” Later, when Pacelli became Pope Pius XII, he sent a letter expressing confidence in the leadership of “the illustrious Hitler.’’

Did Pius display hatred of Jews?

Not at all. But his opposition to Hitler’s “Final Solution” wasn’t exactly staunch. When the Nazis arrived on the scene in the 1920s, Pius, like many other fierce anti-communists, saw them as a bulwark against Bolshevism. By the mid-1930s, though, he was privately calling Hitler “a fundamentally wicked person” who was “capable of trampling on corpses.” But his public actions were more ambiguous. By late 1942, Pius knew from many sources that millions of Jews were being exterminated. Yet he declined President Roosevelt’s request to denounce the genocide, and would not sign the Dec. 17, 1942, Allied condemnation of Jewish persecution. A week later, in his Christmas broadcast, Pius grieved for victims who, “only by reason of their nationality or descent, were doomed to death or progressive extinction.” But he chose not to cite the Jews by name. The next October, just a few hundred yards from his window, more than 1,000 Roman Jews were rounded up by German troops stationed in fascist Italy, for deportation to Auschwitz. Pius was urged to intervene, but declined.

Why didn’t Pius speak up?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He apparently feared that doing so could have brought the Nazis’ wrath, and perhaps even the destruction of the Vatican. Pius did have reason to worry about reprisals: In July 1942, after the Catholic Church in Holland condemned the persecution of the Jews, the Nazis responded by deporting to concentration camps hundreds of Dutch Jews who had converted to Catholicism. This so horrified Pius that he reportedly burned his own planned denunciation, explaining that it “could cost the lives of perhaps 200,000 Jews.” Many historians counter that the Nazi killing machine was already operating at full throttle, and that Pius had a moral obligation to speak out against one of the greatest acts of evil in human history.

Did Pius oppose the Nazis at all?

Yes, but selectively. In 1940, when Pius received Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop at the Vatican, he confronted him with a list of German persecutions against Christians and Jews alike. That same year, through intermediaries, Pius secretly supported a plot to overthrow Hitler by conveying communiqués between anti-Hitler forces in Germany and British intelligence. Pius’ lifting of “cloister rules” also allowed several thousand Jews to be hidden on Vatican grounds. Benedict and other admirers have credited him with “secretly and silently” rescuing more than 800,000 European Jews, whom priests and nuns either hid or helped escape. But the extent to which he was personally responsible is disputed. “The pope knew that priests and monks and nuns in Italy were helping Jews,” says Holocaust scholar Susan Zuccotti. “But he did not ask them to and he did not help them, and, indeed, there is evidence of Vatican discouragement of rescue.”

So did he help the Jews or not?

Available evidence indicates that Pius XII took a very cautious stance toward opposing the Holocaust, declining to take any steps that might have angered Hitler or caused problems for the church. He was hardly “Hitler’s pope,” as some have called him, but critics have reason to question the saintliness of his wartime activities, since saints are

usually willing to die for their moral principles. “Somebody needs to step up and present a compelling case for Pius XII to the world,” Vatican analyst John L. Allen writes in National Catholic Reporter, “helping the average person appreciate why Catholics might look upon him as a model of holiness.”

Saintly pontiffs

Only 78 of Pope Benedict XVI’s 264 predecessors—or less than one-third—have become saints. All but five reigned during the first millennium; one of them, Pius V (1566–72), wasn’t canonized until 140 years after his death. But most recent popes seem destined for sainthood. Pius X (1903–14) was canonized in 1954, while Pius IX (1846–78) and John XXIII (1958–63) were both beatified—the last step before sainthood—in 2000. Beatification for Paul VI (1963–78) has begun, as has a campaign to beatify John Paul I, who served for only 33 days in 1978. Vatican analysts suggest the trend may be designed to head off criticism of popes, or could constitute an attempt to further ennoble the papacy, making it likelier that a sitting pope will later be canonized himself. When John Paul II died in 2005, many mourners shouted Santo subito!—“Sainthood now!” His beatification process began a few weeks later.