Haiti: A history of hurt

The devastating earthquake was only the latest blow in two centuries of natural and man-made disasters. Is Haiti cursed?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How poor is Haiti?

It’s the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with an annual per-capita income of just $790. Only sub-Saharan Africa is poorer. Nearly a third of its 9 million citizens are jammed into the capital, Port-au-Prince, many living in squalor in shantytowns that lack basic sanitation and potable water; the illiteracy rate is about 50 percent. Some Haitians are so desperately poor that their diet includes biscuits made of mud and salt that are baked in the sun, and even before last week’s earthquake, food riots have been common. Thanks to an infusion of international aid and some semblance of security provided by U.N. peacekeepers, the situation has improved since the 1990s, when tens of thousands of so-called boat people fled to southern Florida in makeshift craft. Now, in the wake of the quake, officials say that only an unprecedented international rescue effort will prevent Haiti from spiraling into complete collapse.

Has Haiti always been desperate?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Actually, it was once the richest French colony in the Americas, thanks to coffee and sugar plantations run on slave labor that France imported from Africa. In 1804, Haiti became the first black republic in the world to declare its independence, following a 12-year armed struggle against Napoleon’s France. (The only colony in the hemisphere that broke away from its mother country earlier was the United States.) Haiti, which shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic, has many assets, including deep-water harbors, beautiful beaches and mountains, and a rich Creole culture. It’s only a 90-minute flight from Miami. Yet, Haiti has always been a political and environmental basket case. Much of its half of the island has been stripped of trees, cut down to make charcoal for cooking. Its hills are brown and corroded, and its waters horribly polluted. Almost without exception, its leadership has been incompetent, corrupt, or repressive—or some combination of the three. The country has endured 33 coups.

What explains this sorry history?

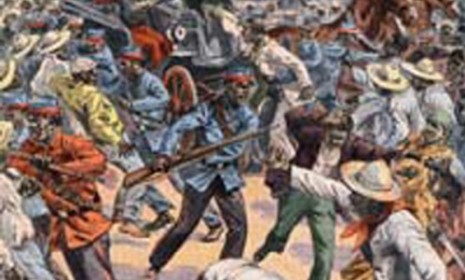

Haiti got off to a wretched start and never recovered. During their revolt against the French, Haitians massacred the white French sugar barons, burning their plantations and killing their wives and children. With the plantation system in ruins, the economy never found its footing. Uprising leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines took power and quickly began imitating his former masters, exploiting the poor and brutally enforcing the social order. He forbade whites from owning property and ruled that blacks must either work on the plantations or join the army. France, arguing that a slave revolt set a dangerous precedent, persuaded the U.S., Spain, and other nations to mount an economic embargo against Haiti. Desperate for international recognition, Haiti eventually agreed to pay reparations to France to compensate plantation owners and their heirs, but the debt proved to be debilitating.

What role has the U.S. played?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Its well-intentioned interventions have both helped and hurt. In 1915, the U.S. occupied the country, fearing the growing influence of a German community there in the lead-up to World War I. A period of stability followed, and by the time the U.S. pulled out in 1934, Haiti’s military was well trained, and a structure for elections was in place. But in 1957, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier was elected in an election rigged by the military, and Duvalier soon threw out any pretension of democracy, declaring himself chosen by God to be “president for life.” The U.S. tacitly supported him, seeing him as a preferable alternative to communism, which had taken hold in nearby Cuba. Duvalier confiscated land held by peasants and gave it to members of the Tonton Macoutes, the paramilitary force he created after disbanding the army, which he feared would topple him. Some 30,000 Haitians died at its hands. Duvalier further consolidated power by reviving Haiti’s voodoo traditions, setting himself up as a voodoo priest. When he died, in 1971, he was succeeded by his son, Jean-Claude, aka “Baby Doc,” who continued his father’s repressive ways. He eventually lost the support of the black majority and in 1986, with U.S. help, fled for France.

What followed the Duvalier era?

Baby Doc’s departure led to a series of violent coups that finally ended in 1990, when populist Catholic priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected in one of the only free and fair votes the island has known. But when Aristide angered the island’s wealthy elite, the military toppled him seven months later. He would eventually return, winning re-election in a questionable vote, and was deposed again, in 2004. The U.N. peacekeeping force moved in that year, and observers say that in recent years, life in Haiti had started to improve. Lawlessness had been reduced, the AIDS epidemic had been curbed, and more aid had been reaching its intended recipients. “There was hope that had not been present for years,” said Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. “And along comes Mother Nature and just flattens it. It’s biblical, the tragedy that continues to daunt Haiti.”

Natural disaster central

When it comes to natural disasters, Haiti seems to have a bull’s-eye painted on it. Last week’s earthquake came in the wake of four hurricanes or tropical storms in 2008 that killed hundreds. Other killer storms and floods have struck throughout the decade. Indeed, the earthquake is, officially, the 15th natural disaster to strike Haiti since 2001, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development. Prior to the earthquake, 3,000 Haitians had died in natural disasters since the turn of the century, and hundreds of thousands had been displaced. The island has the misfortune, among others, to be located directly in a geological fault zone, making it susceptible to earthquakes, and its location in the Caribbean makes it a sitting duck for hurricanes. Environmental degradation and poverty, of course, only compound the problems. “If you want to put the worst-case scenario together in the Western Hemisphere for disasters,” says Richard Olson of Florida International University, “it’s Haiti.”