The last word: When lightning strikes

It frightens, thrills, and sometimes kills us. After a perilously close call, writer Jill Frayne offers a hymn to summer’s natural fireworks.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the summer of 2002, I was camped at the mouth of a river, lying on my Therm-a-Rest waiting out a thunderstorm, when my tent was struck by lightning. It was over before I knew what had happened, before adrenalin had any role to play, before fear took over. My tent poles took the charge and I was spared, completely. The narrow escape got me asking around. How often does this happen? It turns out everybody has a lightning story.

Floyd Woods, a retired truck driver from Ardbeg, Ontario, was 12 years old in 1943 when his house was hit. The strike shot through the radio antenna, exploded in the living room into a blue fireball that roared down the hall, lifting up the linoleum runner by the tacks, ripping the nails out of the floor, splintering the house walls as fine as kindling before it ran off over the bedrock outside and died. Woods’ guitar was hanging on the wall over his bed. Sixty-five years later, he still shakes his head: “That strike burned the guitar strings off, bing, bing, bing, threw me right out of bed and across the room so I ached for a month. Nothin’ will move you faster than lightning. Nothin’.”

When my tent was hit that July evening, I was on a kayak trip, camped on the bony finger of rock where Ontario’s French River fans into Georgian Bay. We were about to enjoy an appetizer of fresh perch when the wind suddenly came up. Clouds stacked up so quickly it was as though someone hidden behind the scenes was furiously working a bicycle pump. Our guide squinted at the sky and ordered us into our tents. “Get on your mats. Stay until I give the all-clear.” I lay down, marveling at the near-dark at 6 o’clock.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Georgian Bay is storm-swept all summer long, but this was impressive. In minutes, pattering rain built into a downpour. Thunder boomed continuously, tearing the sky apart. A crack seemed to go off inside my head, and then, suddenly, blue light ignited the tent and streaked down the poles. It was over in a second, maybe less, but the air inside hung there, hazy and peculiar smelling. With the all-clear signal, we gathered outside under the tarp, sunlight gleaming in the wet hollows of the rock. One kayaker had taken a ground charge through his hand when he leaned off his mat. His wife’s thigh showed the bloom of a bruise, by way of her husband or from a side splash—we didn’t know. Another man, too tall for his mat, had been shocked through his feet. The flap of my tent was pinholed with lesions, and one of the sectioned poles had fused solid. Later, I strapped it to my kayak like an antenna. A reminder.

The ball of blue fire that rolled through Floyd Woods’ house was a rare example of a phenomenon that is anything but rare. The planet ripples with lightning. At any given time there are 1,500 to 2,000 active thunderstorms on Earth. If viewed from space, Earth would appear to be pulsing with storms. Of all the forces of nature, lightning is peerless in its intensity, in the magnitude of its release in a single instant. It is the ravishing dagger, the fire bolt joining earth and heaven, part of the original chemical soup. It might not be too great a leap to suppose lightning supplied the electric jolt that kindled organic life.

Like every force of nature, lightning gives and takes away. Its great boon is that it exudes nitrogen, crucial to plants. But its touch is also deadly: Lightning scorches whatever it strikes. It chars, explodes, sears. We are thrilled by its terrible beauty, pulsing in and from the clouds, jagging out of a riven sky, but lightning strikes cause huge crop damage, ignite forest fires, and can, of course, be lethal to living creatures.

It is not just a direct hit that is worrisome. Through its charge, lightning can harm any creature within a 50-meter radius of the strike point. We can also be harmed collaterally, by getting knocked off our feet by the percussive force or walloped by a struck tree. We cannot outrun it—lightning comes to earth at an estimated 136,000 miles an hour—and we cannot dress for it, as a bolt reaches temperatures of 50,000 degrees. We can only hide.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

People ask, “Who is most likely to be struck by lightning?” Something stirs in the mind about metal objects, and you might guess golfers, out there on the open fairways with 4-irons raised to the sky. You might not think of farmers, perched on their tractors and insulated by rubber tires, but in fact, farmers it is. Where we need protection is overhead, not on the ground. As it descends to earth, lightning current is drawn to isolated objects, anything taller than others in its field. This might be a lone tree, a skyscraper, a mound of granite, or you in your small craft on open water. Closed vehicles are a good choice for cover because the metal that encases them channels the charge into the ground. But tractors aren’t always covered, and farmers are often the tallest object in an open space, plowing or haying as the summer day heats up.

Thunderstorms do give notice—wickedly short, usually, but always distinctive. To recognize such warnings, one needs to learn the rudiments of storms, which is what I did after my brush on Georgian Bay. Storms rely on the rapid, sustained uplifting of air, especially warm, moist air. This is why they occur frequently in summer, when the ground has grown hot by late afternoon. Open fields heat faster than forests or water, rocky slopes faster than ground covered by vegetation; hence the sudden onrush of the storm we experienced, parked on a warm rock, just at cocktail hour at the end of a hot day.

Convection fuels thunderstorms, either from warm air rising off the ground or from a drop in temperature in the atmosphere. Cheery, popcorn-white clouds in the sky mean unstable air has stopped rising and has reached the dew point, when its temperature equals that of the surrounding air. These cumulus clouds can persist for days, but if warm thermal air keeps pushing up, they often develop into cumulonimbus clouds. When this happens, an aerial game of pinball begins. Droplets bounce around, collide, pick up grit, old volcanic ash, the detritus of life below, all of it freezing into ice crystals in the lower atmosphere. Air travelers experience this as turbulence, their plane lurching in the chaos, the cabin windows dashed with rain or hail.

On the ground, this intense interior action looks like clouds mounting into dark towers. Inside the cloud, ice crystals and raindrops are zinging about in all directions, slamming into and fusing with one another, growing larger and heavier—until they start falling through the cloud as rain or snow or hail.

Lightning gets into the action through an electrical charge that builds during these collisions. When a beauty of a storm is brewing, a negative charge heats up at the base of the cloud. The earth’s surface tends to be negatively charged, and since like charges repel, current at the bottom of the cloud draws away from the ground, leaving a positive charge in the air. This is that pre-storm sense one gets, the hair on the head lifting slightly, the air freighted with electricity.

It’s in the nature of air to act as a buffer, to resist electrical flow, and for a time it contains the mounting charge. But it can’t hold out forever. At a certain point, the negative charge from the cloud expends itself, not all at once, which would be an atomic

reaction, but haltingly, in a “stepped leader” about as thick as a pencil. This negative charge gropes toward the ground, moving in a searching way, like a lonely drunk in a bar looking for a connection. Eventually, it attracts a positive charge from something tall on the ground—a tree or a tower, a farmer on a tractor. When lightning strikes, the charges have connected in a streamer, a flood of positive current that surges back up into the cloud, spectacularly hot, so intensely superheating the surrounding air that a shock wave bulges out, faster than the speed of sound.

Thunder is the sonic boom we hear when the percussive force breaks the sound barrier. Once the stepped leader from the cloud locks to the streamer from the ground, a channel opens for pulses of electricity to pass through, producing several flashes. We see the lightning before we hear the boom, but the thunder actually occurs first; the speed of light outraces the sound of thunder to our senses. In lightning’s defense, it’s only doing its job. It’s the celestial housekeeper, balancing an overcharged heaven and earth.

Safety instructors say that if you hear thunder or see lightning, avoid dithering. Don’t bother to stop and count out the seconds between the flash and boom. Instead, move to an area of less exposure immediately. Get off the water, down from the ridge, away from bare ground. Look for a stand of trees of similar height—but avoid tree roots—or look for ground covered in vegetation. And remember, lightning is a master of afterthought. It can strike from a clear blue sky, well after the storm has been squelched. Stay where you’ve chosen to be for 30 minutes after the last clap.

Our encounter on Georgian Bay created quite a stir among wilderness safety instructors in the area. Retreating to our tents was throwing the book out the window, according to some of the instructors, who advise that if you can’t retreat to safe ground, the best approach is to present as small a contact surface as possible. Get your metal-framed pack off your back, duck down in the “lightning crouch” (scrunched on the balls of your feet, your head covered by your arms), and wait it out.

But when Tim Dyer, owner of White Squall Paddling Centre, just off Georgian Bay, heard what we had done, he stood by his guides’ decision. “Safety in a lightning storm is a mug’s game,” he says ruefully. “Given the choice between crouching in a position only a human pretzel can assume or heading for the—all right, dicey—shelter of my tent, I’ll get into my tent.”

I continue to be baffled by why the strike that hit my tent was so glancing. Was it side splash, the point coming to ground somewhere nearby, leaping a fallen log or tag alder and hitting my tent somewhat tired out? Or was it the speed of the bolt that spared me, current zooming through the poles at 136,000 miles an hour? But if lightning’s temperature is thousands of degrees, why didn’t my tent simply vaporize?

I’ll never know. What was plain in that particular storm, in that particular place, is that my aluminum poles took the heat. Another time, who knows?

From a longer article that appears in the July/August edition of The Walrus © 2008 by Jill Frayne. Used with permission of the author.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

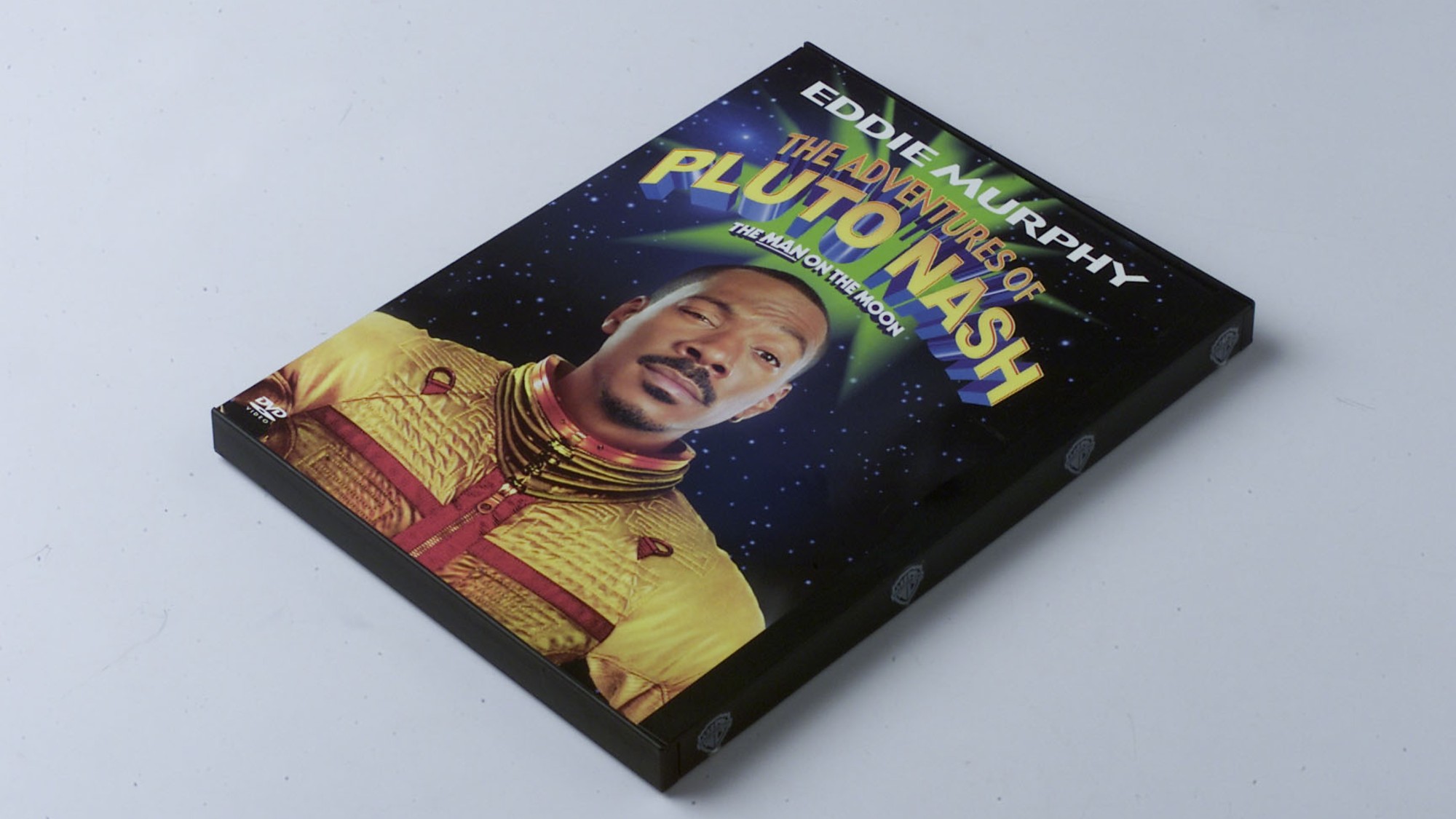

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings