The struggle over sharia

A Nigerian woman has been sentenced to death by stoning under sharia, or Islamic law. What are sharia’s precepts?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is sharia?

It is an all-encompassing body of Islamic spiritual and social duty. Literally, the word is Arabic for “the road to a watering hole.” Figuratively, it means “the path of God.” Sharia is drawn from the Koran, the teachings of the prophet Mohammed, and scholarly interpretation. It governs most aspects of observant Muslims’ waking lives, including dress, eating and drinking habits, business affairs, and sexuality. In some Muslim countries, this code of conduct is the law.

How does it instruct Muslims to live?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Virtuously and humbly. “The true Muslim,” instructed Mohammed, “is the one who hurts no one by word or deed.” Sharia is considered the literal word of Allah, and its tenets include the five “pillars,” or key practices, of Islam. These are shahadah, the belief in one God and Mohammed as his prophet; zakat, the giving of alms to the poor; salah, the five daily prayers made toward the holy city of Mecca; hajj, the pilgrimage to that city, which each Muslim should make at least once; and sawm, the dawn-to-dusk fast during Ramadan.

Is sharia harsh?

Followed literally, it can be medieval. Sharia divides all human actions into five categories: obligatory, meritorious, permissible, reprehensible, and forbidden. Among the reprehensible and forbidden acts are drinking alcohol, eating pork, theft, slander, highway robbery, murder, adultery, and losing one’s faith. Traditional punishments include whipping and the amputation of limbs. For the most severe crimes, the penalty can be decapitation, crucifixion, or death by stoning. In Saudi Arabia, where sharia governs civil society, these harsh penalties are still meted out. Women are shrouded and segregated from men; suggestive Western photographs censored; and criminals punished harshly. In the capital city of Riyadh, beheadings are carried out on a brick-and-marble plaza that some have dubbed “Chop-Chop Square.”

What does sharia say about women?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That they are meant to be subordinate to men. “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has made the one of them to excel the other,” the Koran says. “Therefore the righteous women are devoutly obedient.” It is on the basis of passages like this that women in many Muslim countries cannot be educated, inherit property, or travel. They can be divorced at their husband’s whim, have their children taken away from them, and be bequeathed to the nearest male relative.

Is sharia consistently practiced?

Actually, no. Today there are four major schools of sharia thought—down from 19 in antiquity—and all are considered equally legitimate. They disagree on matters large and small, including, for example, whether a thief must have his hand cut off. Some scholars say sharia teaches mercy toward those who are so poor they steal out of need; therefore amputation should be meted out only in an ideal Islamic state with no gaps between rich and poor. Today, in secular states like Egypt, Syria, and Malaysia, governments pay only lip service to sharia. In theory, Iran’s fundamentalist theocracy operates under sharia, but the pragmatic Ayatollah Khomeini declared it could be subordinated to state interests. So Iranian women can work, vote, drive, ride bicycles, and hold elected office.

Is modernization inevitable?

That issue has sharply split the Muslim world, giving rise to the fanatic extremism of Osama bin Laden and his al Qaida brethren. The fundamentalists believe it is the world’s destiny to be governed by sharia law in its most rigorous form; their ideal state was Afghanistan, as ruled by the Taliban. There, women could not leave home unless completely covered in a burqa and accompanied by a male relative, and men were beaten or jailed for not growing their beards to a prescribed length. Anything smacking of Western influence was considered “unclean,” including—to quote the official penal code—“music, wine, lobster, nail polish, firecrackers, statues, sewing catalogs, pictures, [and] Christmas cards.” A former soccer stadium near the capital, Kabul, became the staging ground for public executions. There, women were shot point-blank in the head, and convicted homosexuals were lined up in front of walls that were then bulldozed by tanks.

Are reformers gaining ground?

Slowly, with the greatest progress coming in the area of women’s rights. In 1999, the Emir of Kuwait granted women the right to vote, but conservatives in parliament narrowly blocked the effort. Egypt recently made it easier for women to divorce; in Bangladesh, grass-roots groups are teaching them how to run for elected office. Reformers tend to base their appeals on ancient Islamic principles. They point out that when Mohammed was chosen to lead all Muslims, a delegation of Arabian women offered him support. Thus, they say, Muslim females were exercising their political rights 14 centuries ago. Khadija, Mohammed’s first wife, actually proposed to him and continued to manage her own business after they were married. Mohammed himself stated that seeking knowledge is the obligation of every Muslim, male or female. “It’s clear that in the prophet’s day,” said sociologist Abubaker Bagader, of King Abdul Aziz University, “women led very public lives.”

The face of oppression

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

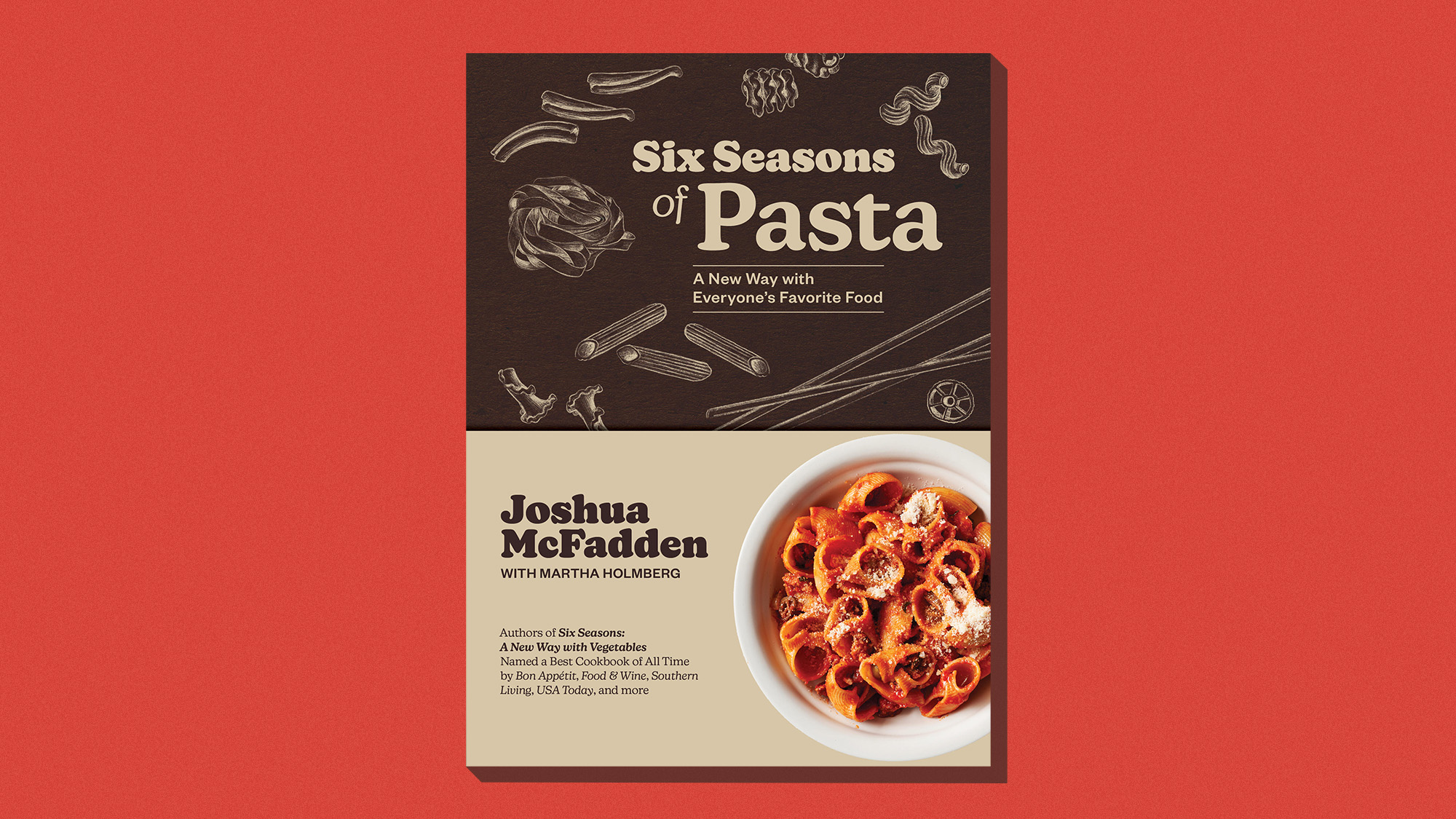

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.