Sex and power in Washington

A tragic missing-persons case turned into a sex scandal with reports that Chandra Levy had been the lover of Rep. Gary Condit. What has been the fate of other Washington politicians caught having affairs?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Are Washington sex scandals a recent phenomenon?

They are nearly as old as the republic itself. In 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton began a torrid, year-long affair with a married beauty, Maria Reynolds. Hamilton couldn’t tear himself away, even after Reynolds’ husband began blackmailing him. The lovers exchanged passionate letters, such as this missive from Reynolds: “Gracious God, if I had the world, I would lay it at your feet. If only I could see you. Oh, I must, or I shall lose my senses.” When a delegation of congressmen demanded to know if Hamilton was stealing treasury funds to pay off Reynolds’ husband, Hamilton published a pamphlet, “A Public Confession of Adultery.” His detailed admission defused the scandal and he remained in office.

Have politicians’ sexual peccadilloes always been big news?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Until the past 30 years, the press generally kept silent about the many rumored affairs on Capitol Hill. The dashing James Garfield, for example, escaped public embarrassment in 1862, when he had a brief but torrid love affair with Lucia Gilbert Calhoun, an 18-year-old New York Times reporter. His wife, Lucretia, learned of the liason and privately denounced his “lawless passion.” She stuck by him, though, and in 1880, Garfield won election as the nation’s 20th president. He was assassinated four months after taking office.

Were there exceptions?

Quite a few. The most dramatic came in 1887, when the Louisville Times reported, in surprising detail, how the married Rep. William Presoton Taulbee was “trysting” with an 18-year-old woman who worked in the U.S. patent office. Enraged, the corpulent Taulbee physically threatened the Times’ short, slight reporter, Charles Kincaid. Their feud grew in rancor for three years, until finally, on Feb. 28, 1890, the bullied reported confronted the congressman inside the Capitol, pointed a pistol at his head, and fired. Taulbee fell, mortally wounded, and died 11 days later. Kincaid was later acquitted of all charges.

When did the rules about reporting sex scandals change?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some media experts say the new era began 32 years ago, when Sen. Ted Kennedy drove his Olsmobile off a bridge on the snall island of Chappaquiddick, Mass., drowning passenger Mary Jo Kopechne in eight feet of water. Kennedy didn’t alert police until the next morning, and ultimately pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident. The fact that a woman had died opened the door for reporters to challenge Kennedy’s claim that he simply got lost taking the young campaign worker home.

Since then, how has the press responded to sex scandals?

It’s made the most of them. In 1974, a patrolman pulled over Rep. Wilbur Mills (D–Ark.) for speeding at 2 a.m. near the Jefferson Memorial. His passenger bolted to escape notice, but a TV cameraman recorded her rescue from the Potomac River tidal basin. She turned out to be a stripper, Annabella Battistella, who performed under the name of “Fanne Foxe, the Argentine Firecracker.” Mills, the powerful chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, won re-election, only to be forced out of his chairmanship weeks later, after he was spotted, apparently thoroughly inebriated, cavorting about on a Boston burlesque stage with Foxe. The stink led Mills to end his 38-year House career and begin campaigning against alcoholism. Beware, the chastened Mills lectured, of “foreigners who drink champagne.”

Who else was exposed?

In May 1976, The Washington Post reported that another longtime congressman, Rep. Wayne Hays (D–Ohio), was paying Elizabeth Ray to be a committee secretary, even though she admitted “I can’t type.” Her $14,000 annual salary, she said, was for having sex with the congressman. “Hell’s fire!” Hays said when the story surfaced. “I’m a very happily married man!” Hays launched a re-election campaign, then dropped out, and finally resigned his seat.

Are scandals always politically fatal?

They often are, but not always. In 1983, two congressmen were forced to admit to having sex with 17-year-old congressional pages—Rep. Daniel Crane (R–Ill.), with a female, and Rep. Gerry Studds (D–Mass.), with a male. Family man Crane made a tearful apology; lifelong bachelor Studds declared, “I am gay,” and declined to apologize. The revelations caused an uproar, and House investigators spent $2.4 million and a full year to ferret out reports of drug use and widespread sexual misconduct in the Capitol. In the end, the Ethics Committee censured both men. Crane lost his next election, while Studds won several more terms. Twelve years later, Sen. Robert Packwood, chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee, had to resign after a three-year battle against charges he had sexually harrassed 10 women. When faced with public accusations that he had groped and kissed many unwilling aides, Packwood said he was “sincerely sorry” if any of his advances were “unwelcome.”

Did these scandals inspire Washington to be more chaste?

Apparently not. Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt offered $1 million in 1998 for stories of illicit sex in Washington, amid the impeachment of President Clinton for lying about his affair with Monica Lewinsky. When Flynt said he would release a bombshell report detailing House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s sexual history, Gingrich resigned. Rep. Robert Livingston was to succeed Gingrich, but also resigned after admitting he had cheated on his wife several times.

What they said

- “The statute of limitations has long since passed on my youthful indiscretions.”

—Rep. Henry Hyde (R–Ill.) in 1998, about an affair he had in 1965, at the age of 41 - “I have on occasion strayed from my marriage.”

—Rep. Robert Livingston, before resigning from the House in 1998 - “I may have been an excessive hugger.”

—Rep. John Peterson (R–Pa.), after several women accused him, in 1996, of fondling and sexually harrassing them - “Thinking I was going to be Henry Higgins and trying to turn him into Pygmalion was the biggest mistake I’ve made.”

—Rep. Barney Frank (D–Mass.), after admitting he paid hustler Stephen Gobie $80 for sex, then hired him as a valet

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

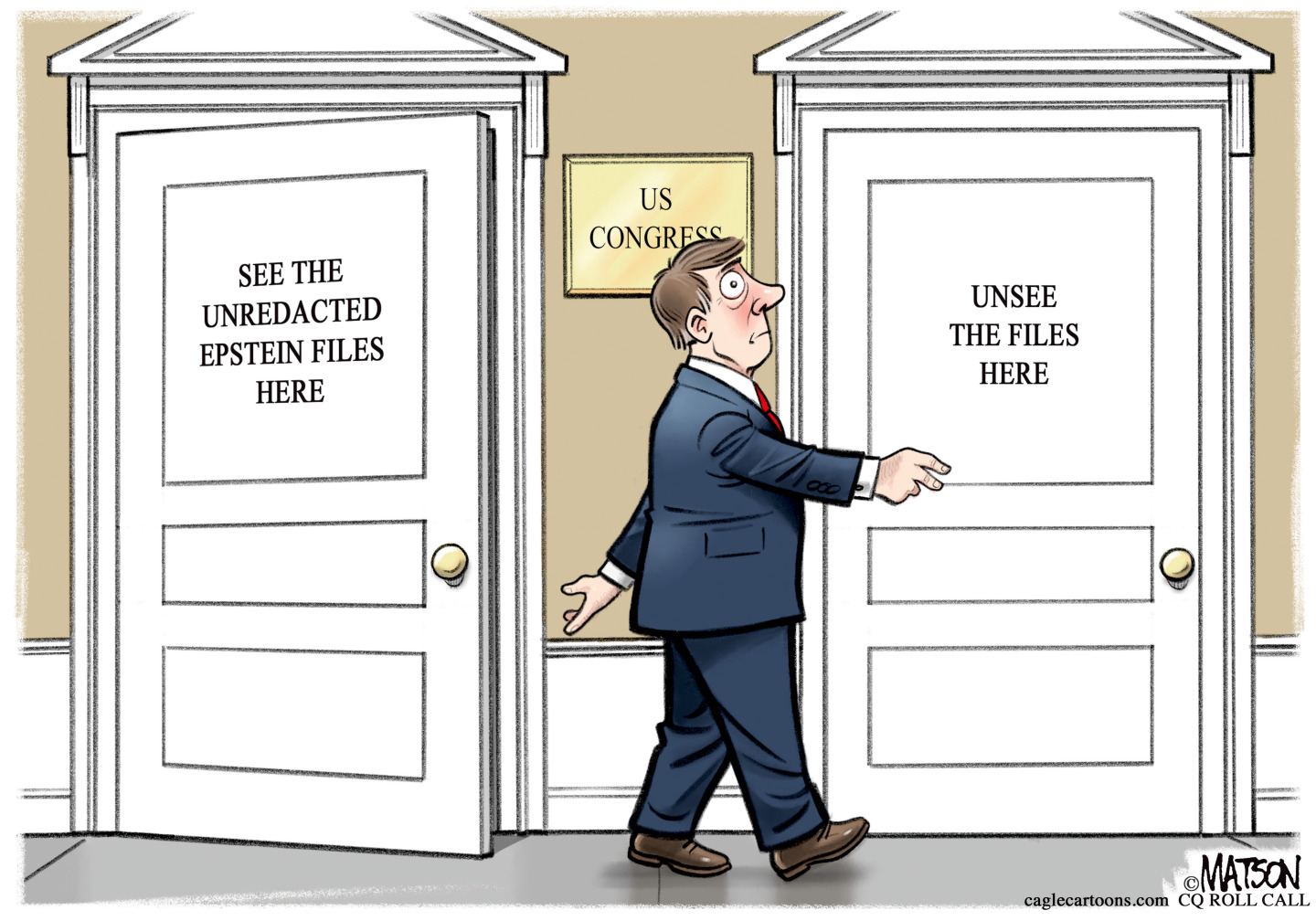

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand