The Blair Witch Project: An oral history

The first chapter in a four-part series

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In October 1997, two unknown, first-time filmmakers shot a micro-budget horror movie in the woods in Maryland. Their success was extraordinary: The Blair Witch Project became a $248 million global phenomenon. Along the way, the filmmakers revolutionized the idea of a "blockbuster," proved the value of viral marketing, and launched an entire subgenre of cinematic horror.

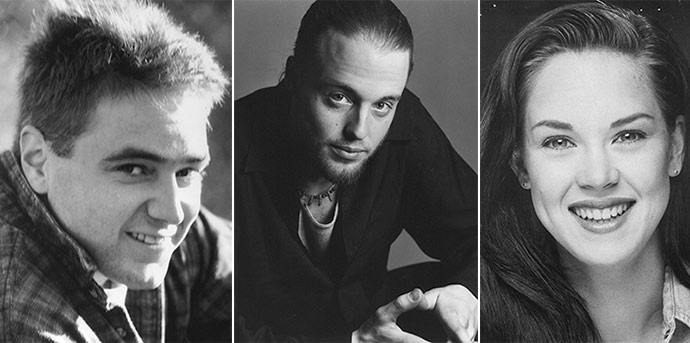

Nearly two decades later, how do the people responsible for The Blair Witch Project feel about the film? In the following four-part oral history, six people involved in the creation of The Blair Witch Project — writers/directors Dan Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez, producer Gregg Hale, and stars Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael C. Williams — describe in their own words the instrumental roles they played in bringing one of the most successful and influential horror films of all time to life.

Part I: Birth of The Blair Witch Project

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Eduardo Sanchez (writer/director): There hadn't really been a great horror movie — or at least a movie that Dan and I had liked — in a long time. I think we had just come back from watching something that was pretty disappointing. I remember we got free tickets to see the Nightmare on Elm Street movie that had Roseanne Barr and Tom Arnold in it.

Dan Myrick (writer/director): We were in film school at the time, and like we'd often do, we'd sit around Ed's apartment or mine, brainstorming stuff.

Eduardo Sanchez: Dan and I just started talking about the kind of stuff that scared us. And we had already talked about stuff like this, but we went out and rented a bunch of VHS tapes. I think we got The Legend of Boggy Creek, Ancient Astronauts. Documentary-style movies — and we found that as we watched this stuff again, it really still scared us. We were just like, "I wonder if this is a way to do something."

Dan Myrick: This idea came up about being in the woods, and you come up to an abandoned house. We started talking it through, and thought about how nifty it would be to shoot a documentary: You're being led to this house, and you can't turn away.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Eduardo Sanchez: The idea was somebody doing some kind of filming in the woods, and then coming up upon a really creepy house and going inside it and finding all kinds of satanic, ritualistic stuff. Candles, pentagrams — that kind of basic satanic stuff. Maybe something is happening in this place, and we shouldn't be here. But then the camera continues and it can't stop, and you're stuck with these people. This camera just going down these hallways, and then you see a door at the end of the hallway, and you know you're going to go in there.

Dan Myrick: We were thinking about the notion of filmmakers being in the woods, and we thought, "What are they doing there? What's the purpose of having the camera on?" We wanted something more than a family outing or something. We wanted something that would be kind of creepy.

Eduardo Sanchez: That was a big discussion. What is it [that they're looking for]? Is it a witch? Some kind of warlock? What the hell is it? And a witch, for us, was just kind of the only thing you could do. We liked the idea of it being centered in Maryland. […] And Maryland is close enough to the Salem witch trials — a really dark period of our history that a lot of people know about.

Dan Myrick: It gave us the reason to have them out there, and to sort of be motivated, and this creepy backdrop: some level of potential paranormal activity, analogous to "Let's explore the Devil's Triangle." The rational side of your head says, "There's a whole host of reasons people are disappearing out there," but it still lays the foundation of, "Maybe there's something else going on here."

Though the initial seed for The Blair Witch Project was planted, it took a long time for the film to grow.

Gregg Hale (producer): Dan kind of offhandedly one night mentioned that he and Ed had come up with a story, while we were all in film school, about three student filmmakers who head into the woods to make a documentary about this witch, and all these terrible things happen to them. They had a couple of the main beats figured out: the stick figures, the house. The hackles on the back of my neck rose up, and I was like, "That's it. That's what I want to do." […] Like most people in film school, I wanted to be a writer-director, and had never really produced anything. I thought that's just what you had to do to get your own stuff done. But I knew Dan and Ed were writer-directors, and I said, "Look, I'll do whatever I have to do to help make this happen, and if that's producing, that's what I'll do."

Eduardo and Dan began hashing out a script that would feel authentic, using as the centerpiece the idea of a video shot by three doomed filmmakers, and the idea of a make-believe documentary that analyzed that footage.

Dan Myrick: We knew it needed a structure. If you back away from the film itself, it's basically a three-act structure. We wanted it to feel real, but we didn't want to go out there and shoot haphazardly. We had a very detailed story plan, where we outlined it as you would a script. And in some ways, more detailed, mapping out hour for hour what they would be doing, where they would be, and the general gist of conversation at any point in time. It was effectively a script without the dialogue written in. It ended up being 38 or 40 pages.

Eduardo Sanchez: Dan and I were just like, "We don't have any money. We can't do any special effects. And here are these kids — we always called them kids — going out and getting raw." It was just in developing the theme of "what happened?" that we would come up with creepy ideas. We had a bunch of ideas that didn't make it in. So once we had an idea, whoever was writing the treatment would just stick the idea in, and then we'd worry about it later. Our plan was always to do a "documentary" about not just the footage, but about the Blair Witch.

Dan Myrick: We came up with this local folklore: that there was this area of the woods haunted by a witch mythology.

Eduardo Sanchez: I named it "Blair" because my older sister had gone to Blair High School, so it was kind of just this name that just popped into my head. It's really crazy now because it's such a perfect name. But like a lot of things, I had to choose a name, and that was the one that was there at the time.

Dan Myrick: [The movie was] motivated by Heather wanting to do this school project surrounding the witch mythology known by the locals.

Eduardo Sanchez: Our biggest thing was to make sure we didn't go too far with an effect, or with what was going to happen. To keep it believable. Because that was the crux of the whole thing: If one frame of that movie didn't look real, we thought that was going to be a huge mistake.

The small creative team behind The Blair Witch Project began the arduous process of casting the three actors at the heart of the film.

Joshua Leonard (actor, "Josh"): I was in my late teens, early 20s, living in Manhattan. Waiting for my big break. I was working as a freelance photographer, and a videographer for a documentary production company. I was in a very weird scene in New York, waiting to figure out what my version of the Great American Novel would be. [laughs] And I had no clue! I was a dumb teenager. I didn't really know at that point whether I wanted to be a documentary filmmaker, or an actor, or a photographer, and was kind of pursuing all things simultaneously. […] I was broke and living in Manhattan, and was looking for the next cool job. A friend of mine had given me a heads-up about [Blair Witch] because the specific prerequisite of hiring somebody to play my role was that they needed somebody who could operate a camera.

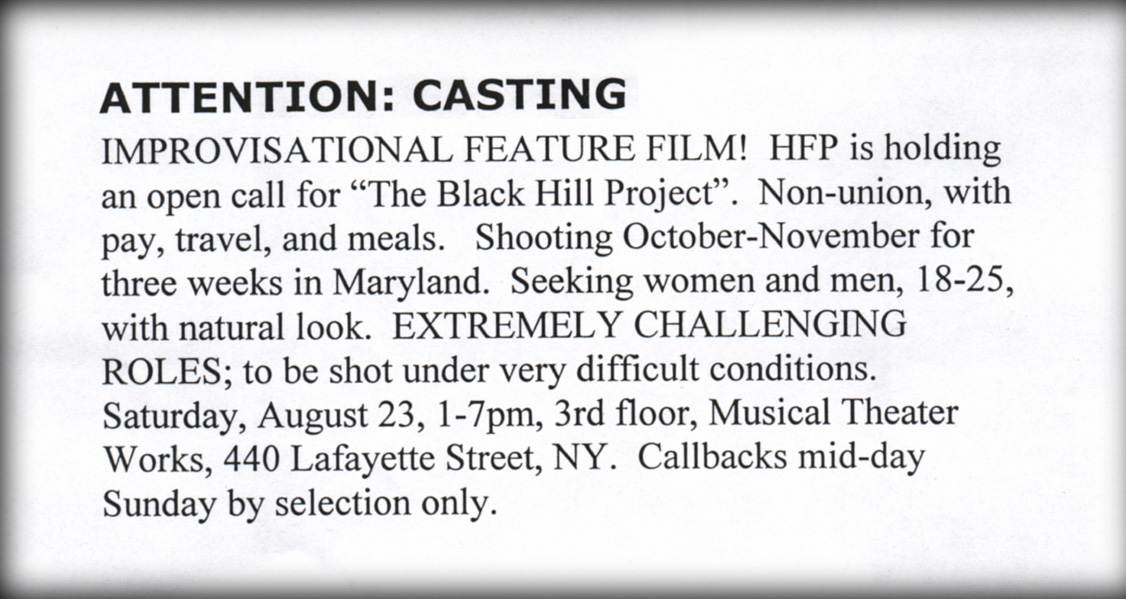

Dan Myrick: We held casting processes in Orlando, L.A., and New York. We went in knowing we wanted improv actors that were quick on their feet. We set up the casting process that way: We had them come in and improvise their auditions, to weed out a lot of people that weren't dialing in immediately.

Joshua Leonard: I went through an audition process, but not the kind of a rigorous audition process that [costars Michael C. Williams and Heather Donahue] wound up going through. I went in on what I believe was the first casting session, which was Ed and Dan. Probably a year prior to the final casting session, which is where they discovered Mike and Heather. I came in with my camera, looking how I looked at the time. I was probably wearing some dumb cowboy hat. And we just did a mini-improv session, and they said, "You've got the job. Let us go out and raise the rest of the money to make this film, and we'll call you back."

Eduardo Sanchez: We showed up to New York [for the final casting session], and there was a line going down the steps to audition for us.

One of the many actors to audition that day was Michael C. Williams, a recently graduated theater major who stumbled onto the open casting call in an issue of Backstage Magazine.

Michael C. Williams (actor, "Mike"): [The magazine] said it was an independent feature film that was going to be improvised and shot in a wooded location, and that camping was a requirement, et cetera, et cetera. It sounded good to me. I had done a lot of improvisation in my training, and I love to camp. So I went for the audition, and there were a few hundred people there.

Eduardo Sanchez: We started asking them questions, then in character. And a lot of people got what we were doing, and a lot of people didn't.

Michael C. Williams: You walked into the room with the directors, or producers, or both, and they didn't say hello or anything. They just came right behind the table and immediately went into improvisation. I walked into the room, and I had Ed sitting there across the table. And he said, "You've just served 10 years of a 25-year prison sentence. Tell us why you should be due for parole." So I just went into it, right there. I did my best Morgan Freeman in Shawshank Redemption impersonation, and I made it to the next round. There was no lag time. You were improvising as soon as you got in the room, and if you weren't ready for that, you were gone.

Michael's audition process was almost identical to the process used to cast Heather Donahue, the young woman whose character served as the driving force behind the film-within-a-film.

Heather Donahue (actress, "Heather"): I'm one of those people who has the idea that you should always do things you're afraid of that don't involve prison or the hospital. There was a little sign that Gregg Hale had posted in the hallway at Musical Theater Works that basically said: "This shoot will be grueling. We don't care about your comfort, but we do care about your safety, and the entire thing will be improvised." And I was like "Game on. This sounds amazing."

Eduardo Sanchez: With Heather — even in the audition and the callback — she just had a crazy… she was able to go to a place that none of the other actresses were going.

Dan Myrick: We had written the original script outline with three guys as the filmmakers. But Heather came in to my audition, and she this great response to our questionnaire that we were giving the actors as they came into the room.

Heather Donahue: When we went into audition, he asked us to improvise, and my improv was: "You have been in prison. You've served nine years of a 25 year sentence, but you're up for parole. Why should we let you out?" And I guess I was the only person that said, "I don't think you should."

Eduardo Sanchez: Dan and I were kind of like, "Well, she's doing that here in New York, with traffic lights outside and the distractions of civilization all around here. Imagine what she could do after a couple of days of not eating full meals, and being lost, and not having a shower, and just being uncomfortable." We knew we had something special, and we knew she was going to be something incredible. And she did.

Heather Donahue: Someone [like my character], who's going to be able to keep the camera on when they're dying, is not a person that you really want to spend a lot of time with. This is not a person who knows when to give up. This is a person who's obsessive, you know? I think they were hoping for someone kind of prettier. But they couldn't find a woman, like an ingénue, who was willing to go. Who was willing to be that kind of terrier. And in retrospect, I kind of understand why.

Dan Myrick: [Heather] gave us this awesome blend of smarts, improvisational skills, and a little bit of this crazy diligence that we needed in our actors, to push forward through the duress that we knew we were going to subject them to. We teamed her up with Josh, who was lobbying to be in the movie early on, and Mike Williams, who we found through the audition process in New York. They just had great chemistry together; the right blend of humor and conflict, and the right look.

Coming in Part II: The cast and crew of The Blair Witch Project share their memories of the film's grueling, 24-hour-a-day shoot.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day