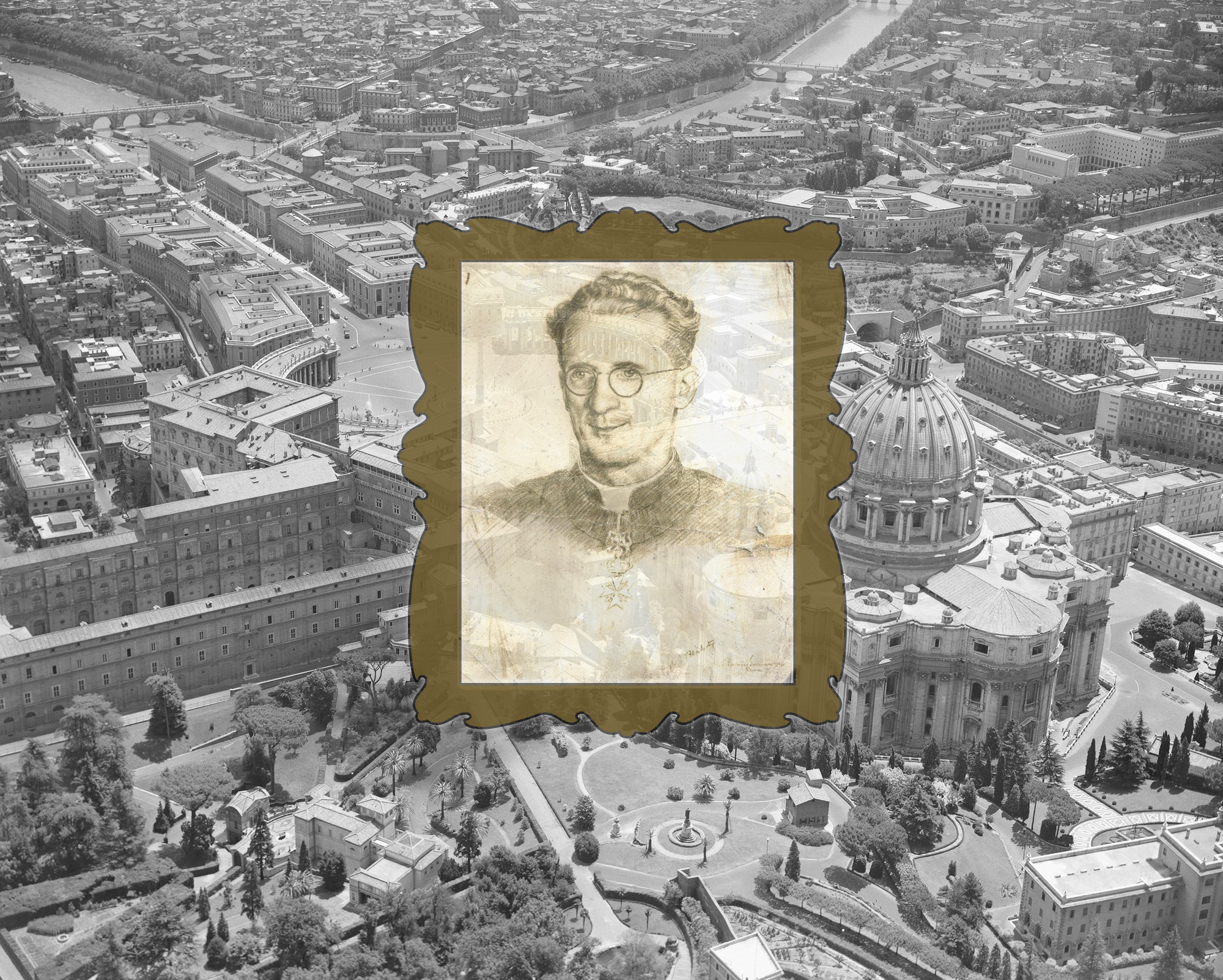

Meet the costume-wearing Irish priest who saved thousands of Romans from the Nazis

Known as the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican, Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty cut a unique figure in the church

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Herbert Kappler became Hitler’s man in Rome after the arrest of Benito Mussolini. An SS officer, he had been an adviser to Italy’s fascist police. Now he was practically in charge of Rome as the Germans imposed their rule there. His first action was to plan the exfiltration of Il Duce himself, which was swiftly accomplished. Next, he began the deportation of about 1,000 of Rome’s Jews to Auschwitz, where they were nearly all killed.

And rather curiously, he ordered his men to paint a white line around the streets that enclosed Vatican City. It was done to send a message to an Irish priest in those city walls. Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty was a rising star at Cardinal Ottaviani’s Holy Office. He was also one of the most effective resistance organizers in Rome. The white line was drawn to remind him that if he were ever caught on the wrong side of it, he would be delivered personally into Kappler’s hands. He would be tortured by fascist police chief Pietro Koch until he gave up every bit of information about his clandestine network, then killed for the crimes of hiding escaped Allied prisoners, anti-fascist agitators (including aristocratic families), and Jews.

Before the liberation of Rome, O’Flaherty and his co-conspirators were overseeing the care of 3,925 men who were wanted by the Gestapo — one bright spot in the controversial historical relationship between the Nazis and the Catholic Church. These escapees were stuffed into the Vatican itself, enrolled into the Palatine Guard, or hidden in monasteries, convents, and a network of private homes across the country and in the city itself. Among these was a safe house that O’Flaherty himself had rented, which backed up against a hotel used as SS headquarters in Rome. O‘Flaherty not only found places of refuge, but helped people avoid Fascist raids, and organized the distribution of food and money for their care.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

O’Flaherty was overdetermined for the role he would play in Rome’s resistance. His father had been a police officer in Royal Irish Constabulary, but had quit in disgust as many native Irish then did, when the British government’s pressure on the Irish increased. O’Flaherty was raised in the thick of Irish nationalist rebellion and civil war, where the technique of conspiring in plain sight would have been impressed upon him. His father went on to work at a golf course, and the young O’Flaherty became obsessed with the game. His later membership in Rome’s golf club gave him access to and familiarity with an extremely large portion of Romam ex-pats and high society.

Because Ireland was officially neutral in World War II, its embassy to the Holy See was the only English-speaking diplomatic house operating in Rome at this time. So it became a magnet for escapees, who often were spirited by the ambassador’s wife to O’Flaherty himself. As one of the few English-speaking men in the curia, he was taken as a translator on Vatican inspections of prisoner camps in northern Italy.

O’Flaherty’s reputation for finding homes and hideaways increased, especially in the days after the arrest of Il Duce, when many prisoners were released before the Germans could begin recapturing them. Escapees often joined his network. Princess Nini Pallavicini, on whose arrest the Nazis placed a considerable bounty, became his partner in counterfeiting documents for escapees, and even printed fake food coupons to keep the costs of feeding so many down. A British officer, Sam Derry, who had jumped from a POW train in northern Italy, became one of the head men coordinating this amateur resistance.

O’Flaherty also regularly crossed that white line. In one particularly memorable episode, Gestapo agents who had been monitoring known O’Flaherty associates spotted the priest entering the home of Prince Fillipo Doria, who would become mayor of Rome after the war. Kappler and dozens of SS agents arrived almost immediately. While the Prince’s staff held them for a few moments, the monsignor went to the basement. There he noticed that the police activity had stopped an in-progress delivery of coal. He climbed the coal pile and pulled in a bag from the street, into which he deposited his clerical garb. He covered himself in coal dust and appealed to one of the coal men for help. He walked right by the SS, posing as a coal-deliverer. O’Flaherty regularly went out disguised as a laborer, or with the company of a female to deflect suspicion. His costume changes, and his spy-like knowledge of Rome’s shortcuts and side streets, earned him the sobriquet the “Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In turn, Kappler kept working to catch him. Kappler tried twice to trap this priest outside the Vatican’s protection, by torturing men until they agreed to try and lure him away at a predetermined time. Both attempts failed. A third attempt was made by trying to send men to O’Flaherty’s regular Sunday Mass. Kappler’s men intended to literally push O’Flaherty over the white line after Mass, where he could be shot, and his death made to look like an escape from arrest rather than an assassination. O’Flaherty’s men learned of the plot, and Swiss Guards surrounded the German conspirators during Mass, before escorting them out. The guards marched them into a side street on Vatican territory that “happened” to have a group of Yugoslav partisans in it. The beating they received got the message across to Kappler.

As fascist police intensified their manhunt, O’Flaherty encouraged people seeking his aid to meet him on the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica, while he recited his compulsory evening prayers. From there, O’Flaherty could see fascist police watching him from across the white line. He could see the Swiss Guards who intended to prevent the police from stepping over. And he could be seen by Pope Pius XII, who was often in his private study at this time of day.

After a resistance attack on Germans and fascist police, Kappler was ordered to execute 10 Italians for every German that died. He had 335 men brought to the Ardeatine caves, and sealed off the tunnels there with explosives, trapping and killing them. Five of the men killed at the Adreatine Massacre were associates of O’Flaherty’s group. The massacre sent a shiver through Rome, but it was the ultimate undoing of Kappler as well. It inspired many more people to cooperate with O’Flaherty, whose group was now informed of nearly every SS raid hours before they happened. And after the liberation of Rome, Kappler would be tried for the massacre and imprisoned for life. He at one point tried to flee to the Vatican for protection. The Swiss Guard turned him away.

O’Flaherty kept an extremely low profile after the war. He received a number of commendations from America and Britain. He sent the honors back home to his sister. He turned down a pension from the Italian government for his service to the resistance. He gave a single interview in 1958, to an Irish journalist. O’Flaherty did not rise much further within the Vatican, due in part to his extreme distaste for Vatican politics, and to the mostly Italian curia’s dislike of him as an “outsider,” particularly one famous in Rome. He spent his time working closely with Cardinal Ottaviani at the Holy Office. Ottaviani so liked O’Flaherty that the austere Italian traditionalist and guardian of orthodoxy became a fan of County Kerry’s Gaelic football team.

But this was not the end of the story. After Kappler was imprisoned, he asked the monsignor to visit him. O’Flaherty became Kappler’s only caller, month after month for many years. These visits troubled communists fearing that a powerful Vatican actor was seeking to free “the executioner of Rome.” No such record of intervention exists. But a few years into this relationship, Kappler, who had tortured men to capture O’Flaherty, asked to be baptized by his wartime adversary.

O’Flaherty’s exploits were well known in the Vatican walls, and certainly known to Pius. They have occasionally inspired biographies, and even a 1983 TV movie, The Scarlet and the Black, featuring Gregory Peck. More recently the Irish-language broadcaster TG Ceathair produced a one-hour documentary about him. But the tale of this costume-wearing, golf club–wielding, anti-SS Irish conspirator and his band of improbable allies deserves the full Hollywood treatment.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spot

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spotThe Week Recommends The trendy hotel recently underwent an extensive two-year revamp

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition