Ed Burns on The Brothers McMullen, finding your voice, and the meat grinder of independent filmmaking

The actor and director sits down to discuss his long career in independent cinema

The ad that ran in Backstage magazine back in the 90s gave no indication of the long film career about to get under way for a young production assistant at Entertainment Tonight.

Indeed, the language was unassuming: low-budget, non-Screen Actors Guild movie seeks Irish-American actors.

"No pay. Will provide lunch."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ed Burns — the son of a New York City cop, a devotee of Woody Allen, and a cinephile who dreamed about committing stories of his own to celluloid — needed actors, because he'd started work on The Brothers McMullen in his off hours. That's the debut flick he put together on a shoestring budget of $25,000 that went on to score the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance exactly 20 years ago.

Like that magazine ad suggests, the film's genesis was unpretentious, but even today, his first attempt behind the camera still represents something of a template that Burns, now 47 as well as a husband and father, has returned to throughout his career. It's about purity of vision, of doing things his own way, whether Burns is turning heads at Sundance, bringing his many later passion projects to fruition, or having one of his films, Purple Violets, be the first feature film to debut on the iTunes store back in 2007.

This summer, he's bringing a TV show to TNT — the 1960s-era New York City cop drama Public Morals, in which he stars and serves as writer, director, and executive producer alongside Steven Spielberg. That, again, is another story he's itching to tell, about a period of history that fascinates him.

In his just released memoir, Independent Ed, Burns spends a big chunk of his time leading up to and building off of the experience of shooting his first film to share why he chose to step into the meat grinder of a Hollywood career the way he did and what he's learned along the way.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It all starts, he tells The Week, with finding your own voice and following wherever that takes you.

"It can be a tough thing to figure out, because all of us have that film or novel or song that sort of inspired us and made us fall in love with the thing we end up doing," Burns says.

For me, it was Woody Allen. I saw those early comedies and started to fall in love with movies. I said, I want to do something like that. But then you have to turn that inspiration into your own thing.

I think finding your own voice can only come from one place, and you're not going to find it the first time out of the gate. It's like Malcolm Gladwell and his 10,000 hours, or the Beatles, doing all those covers, spending all that time in Hamburg. You've got to go through the process of finding it. You've got to be willing to put in the hours and know that a great deal of what you write, at least at first, is going to be terrible. But that's totally okay. [Burns]

Being an independent filmmaker means different things to different people, he continues. For him, it's not about the size of the budget or whether there's a marquee cast involved; it's about shaking off outside influences as much as possible. It's about being independent of the "muckety mucks" who write the big checks but expect to have a say in the kinds of stories a filmmaker like Burns wants to tell.

"You make the choice of which path you want to take," Burns says. "For the most part, I've gone with making it for less money and maintaining creative control."

Which is why, for Burns, it's no contest. Never mind that he spent the ensuing years after The Brothers McMullen put him on the map working as a journeyman actor and director, writing and directing another 10 films since his debut.

He still calls shooting The Brothers McMullen, though, the best 12 days of his life.

Not that the work was particularly glamorous. He shot, for example, inside his parents' home. Scenes had to be scheduled around his actors' other commitments. There was plenty of making do, of setting up quickly and filming scenes in parks and out in the open in lieu of the rigmarole of securing permits and paying for the privilege of shooting where he might have preferred.

His collection of actors included his then-girlfriend, Maxine Bahns. Long before she was a star thanks to shows like Friday Night Lights and Nashville, a young Connie Britton had sent Burns her headshot, and The Brothers McMullen ended up being her screen debut.

The finished film was ignored and passed over for entry into festivals around the county before Burns got it into the hands of Sundance founder Robert Redford. Redford was giving an interview to Entertainment Tonight, and Burns raced after him before Redford caught an elevator, giving him a tape of the film and asking him to take a look at it.

"There's no right or wrong way to make a movie," Burns writes in Independent Ed. "You've just got to figure out a way to get it done. And it won't be easy. But that's not why we do it, is it? We do it because we have no choice. It's who we are."

Today, an on-demand, digital-first world can represent something of a double-edged sword for independent filmmakers. For consumers, the glass is half full, with iTunes, Netflix and the like presenting a cornucopia of film, a plethora of choice. The flipside is that abundance of choice makes the long tail of demand even longer.

Burns, though, is optimistic. When he started out, he explains, a filmmaker needed "real money" to make a movie. Professionals were required, as well as the kind of equipment that wasn't just laying around.

Now, top-flight equipment is more widely available. "It's easier for anyone to get a movie made, and I would argue that's a good thing."

His book is an attempt to dispel some of the myth surrounding filmmaking, and to explain it's like any other craft. A unique voice, thick skin, and a deep love of the work are required, he says, and while he makes clear they don't by themselves ensure success, he's used them to find his own fulfillment and to help keep the self-doubt that confronts any artist at bay.

"You're constantly dealing with it, and I think it's a healthy thing," Burns said.

But you can't let it cripple you. And some people do let it cripple them. You can't be such a tough critic of your work that you end up paralyzing yourself. This isn't something you can teach. You either have it or you don't. If you truly enjoy the process, and I know it's a cliché to say it's about the journey not the destination — but almost everyone I've met who's stayed successful for a long time, the goal was never about the money. They loved playing guitar, they loved telling stories, they loved dancing. That was just what they needed to do. They didn't really have a choice in the matter. This is what I do to keep my head on straight. [Burns]

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

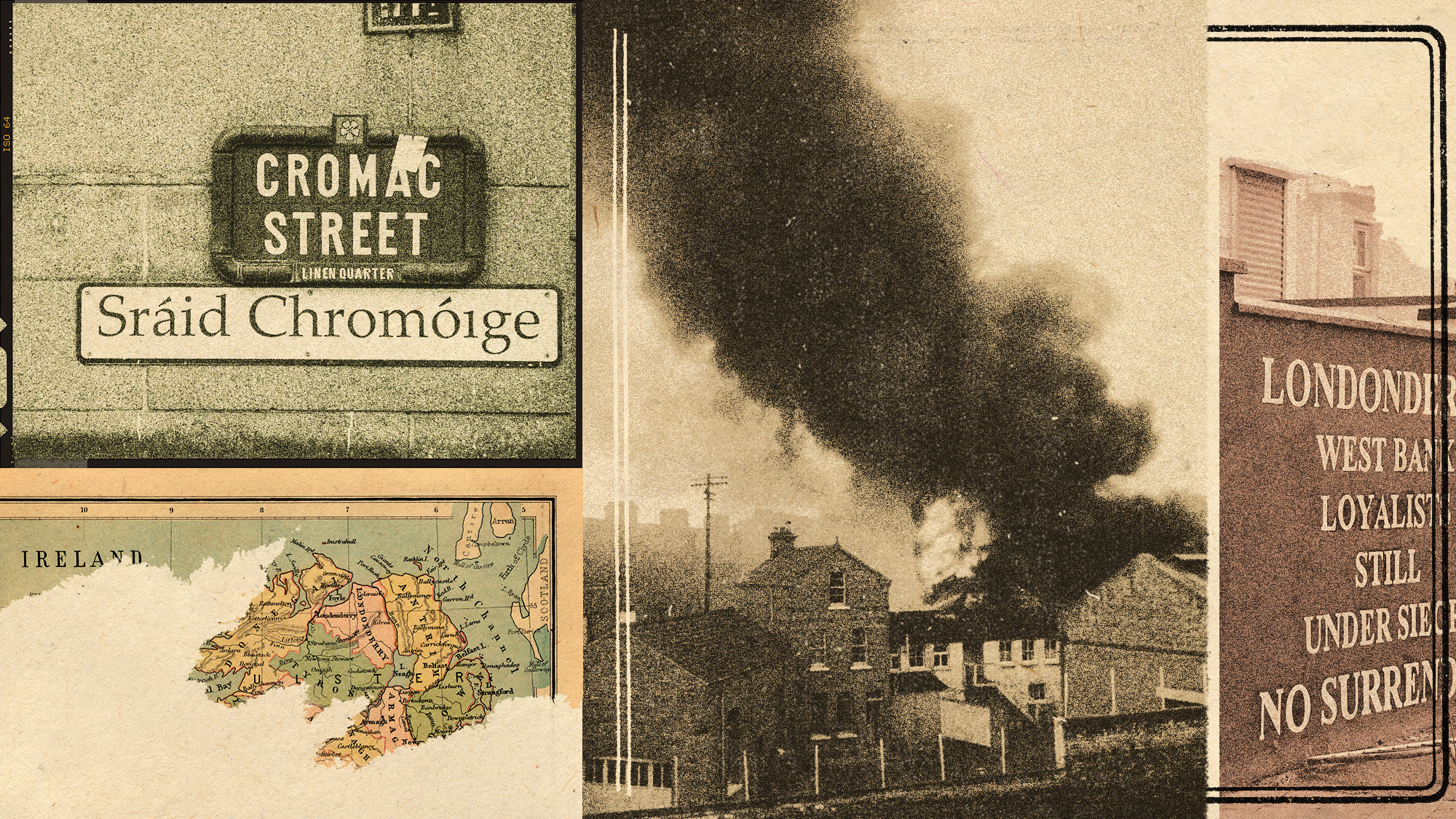

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels