Corporate America is colonizing your mind. And you're letting them.

To overcome this threat, you have to make peace with the sounds of silence

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Our momentary silences in public places are being colonized by corporate interests trying to harvest and monetize the last remaining bits of our attention that can still be captured. Think of the strange commercials on video screens at the gas pump. Or the television screens playing at all times in many corporate office waiting rooms, lobbies, elevators, and taxi cabs.

The invasive, omnipresent stream of messaging takes away the sociability of public spaces, even public spaces that are mostly shared in silence. Some people simply endure the streams coming at them. Others (and put me in this category) tend to take control of the streams of media, escaping behind our ear buds and smartphones.

The whole thing is laid out by Matthew Crawford in a beautiful little piece in The New York Times. And as if to heighten the drama for Times readers, Crawford points out that once ambient attention is monetized, the rich can more easily afford to buy it back:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Silence is now offered as a luxury good. In the business-class lounge at Charles de Gaulle Airport, I heard only the occasional tinkling of a spoon against china. I saw no advertisements on the walls. This silence, more than any other feature, is what makes it feel genuinely luxurious. When you step inside and the automatic doors whoosh shut behind you, the difference is nearly tactile, like slipping out of haircloth into satin. Your brow unfurrows, your neck muscles relax; after 20 minutes you no longer feel exhausted. [New York Times]

This fear of mind colonization by corporate America has long been taken up by fiction writers. Minority Report portrayed personalized advertising that addressed you by name in public. The British series Black Mirror portrayed a future in which people have to pay for the temporary privilege of not watching suffocating, room-sized advertisements for porn.

Crawford is right that we have to re-conceive the idea of our "right to privacy" to include some kind of right to our own attention. And that the people who can afford the silences of the business class lounge are treating "the minds of others as a resource" from which they transfer money to themselves. But the disappearance of creative, thoughtful, and restorative silence is not just due to an invasion of corporate interests. It is also a kind of surrender by common people.

Many of us are absolutely addicted to the distractions offered by our phones, pulling them out and refreshing a stream whenever the mind threatens to wander away with us. As a matter of course, many mass transit commuters, pedestrians, and travelers hide from the noise by turning up their headphones. Many people work with headphones on all day. When was the last time you were truly alone with your own thoughts, with no distractions, for more than a few moments? For most people, the honest answer is probably very unsettling.

We all know some people who instinctively flee from silence. They enter inanities into a conversation that might temporarily fall flat, just to keep the interaction going. They leave a television on all day at home, and feel a need for it especially when they want to fall asleep.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Every so often, studies are conducted to discover just how quickly people find silence awkward or intolerable. Four seconds is all it takes for silence to be painfully awkward, said a Dutch study in 2011. Michael Bittman of the University of New England and Mark Sipthorp of the Australian Institute of Family Studies did some research on young people being addicted to media and concluded tentatively that "their need for noise and their struggle with silence is a learnt behavior." Earlier this year, Science published a study that found college-aged men would rather experience electric shocks than be alone with their own thoughts. One quarter of women and two thirds of men decided to shock themselves rather than spend 15 minutes with their own thoughts.

Given that, some might find the intrusion of television screens at the gas pump a kind of relief. A CNN feed at the airport gate provides the necessary distraction if or when the smartphone battery goes dead.

But why do we feel this way? Bill McKibben wrote of a childhood where "TV was like a third parent — a source of ideas and information, and impressions. And not such a bad parent — always with time to spare, always eager to please, often funny." This is a sharp observation, but it doesn't take us all the way. The anxiety for the "third parent" isn't an anxiety for comfort, but for relief. Relief from what? I hate to venture guesses; every person can be unbearable to themselves in their own way. Some of us want to postpone the court date for self-judgment forever. Others accuse themselves too harshly in the silence of their hearts.

If Crawford is right that our public spaces are being colonized by advertisers that offer distractions and demand our attention — and he is — no effective resistance will be possible so long as majorities of young people find silence intolerable. And make no mistake: Before "elected silence can find us in the airport lounge, more of us have to make peace with it in our homes — and even in our heads.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

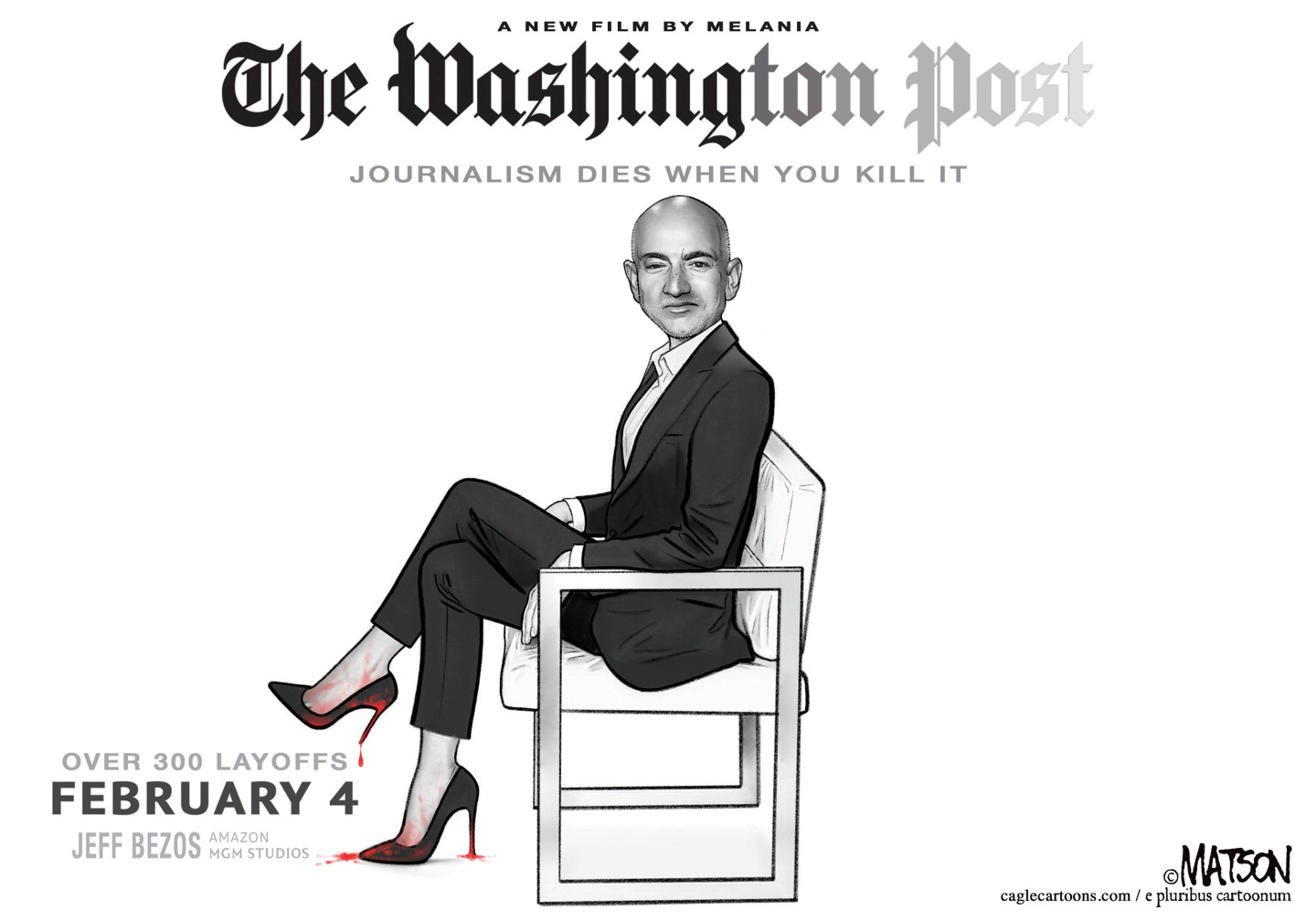

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky