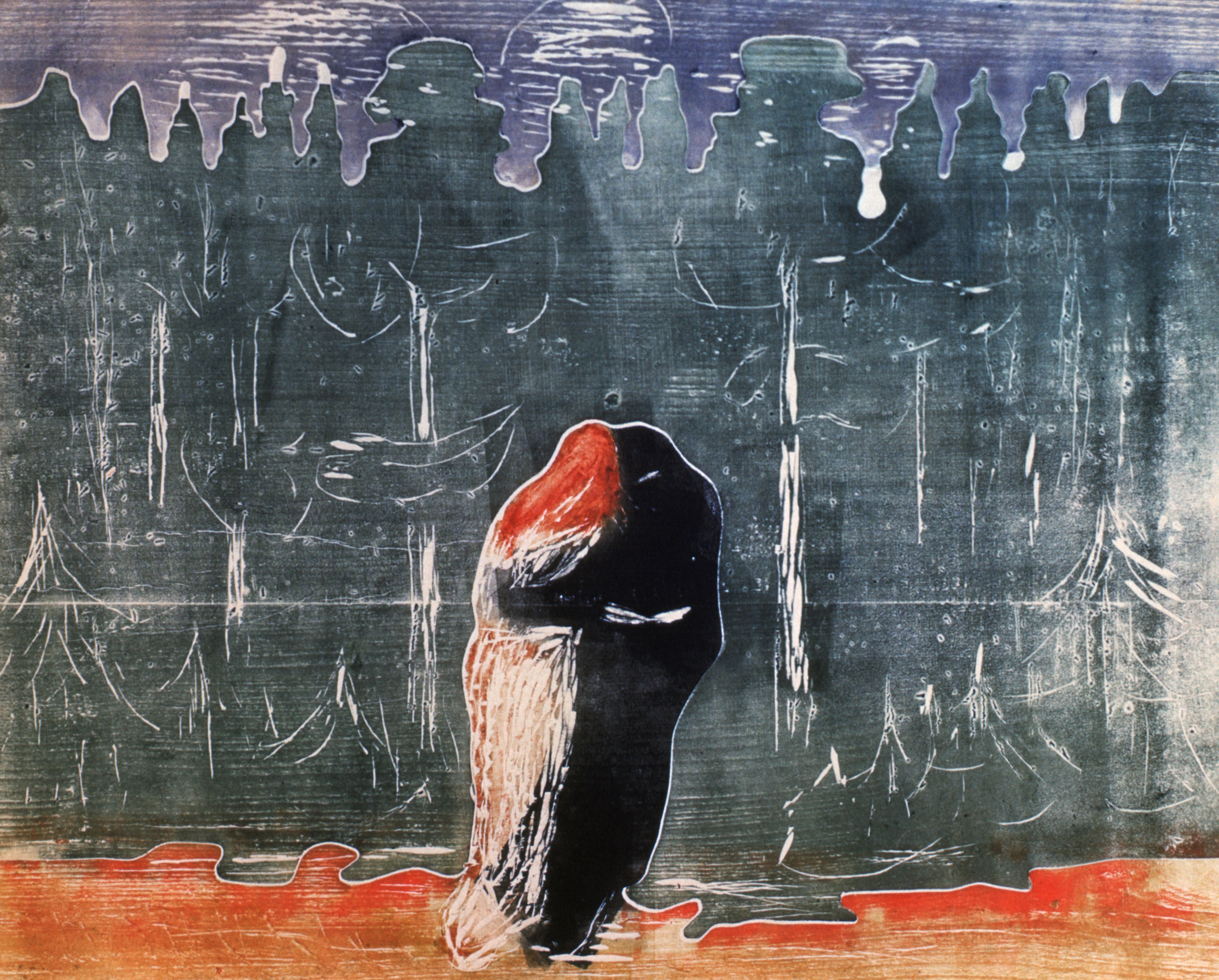

When dying is never, at all, acceptable

We cannot prevent death. But we can rise above it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

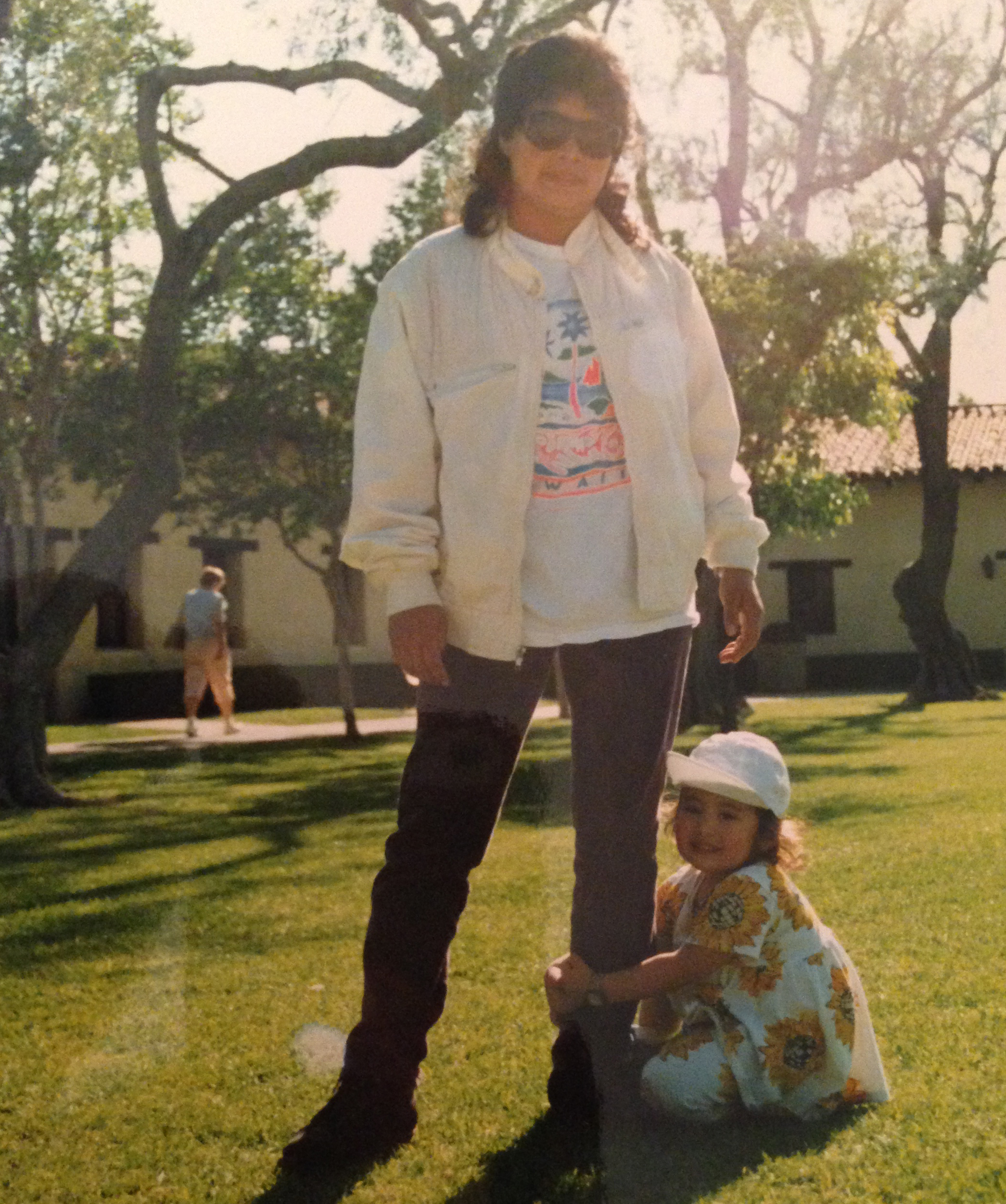

Twenty-two years ago, my parents needed someone to watch over my older brother and I while they were at work. Thanks to a recommendation from a family friend, a prospective nanny named Haydée walked into our home on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in 1993, ready for her first day of work. I was just 6 months old.

For the next two decades, Haydée would be a mother to me in every single way except genetically.

Whether you judge parenthood by diapers changed or habits taught or games attended or tears wiped, Haydée fits the description; she called me "hija mía, trabajo de otra." Sure, my dad took me to father-daughter dances and my mom made lucky envelopes for my elementary school classmates every Chinese New Year. And I love them both. But it's because of Haydée that I can put my hair in a ponytail and know how to fold my laundry and have never smoked a cigarette, not even once.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I remember being not more than 4 years old, sitting on Haydée's big queen-sized mattress in the bedroom we shared for two years, reading her old Silabario workbook. We'd laugh and turn pages and she'd teach me what I thought were just random Spanish phrases. It wasn't until I got to kindergarten that I realized I was fluent in her native language. I repaid the favor years later, reviewing worksheets she'd completed for her English classes and trying in vain to explain to her the inanities of English grammar. She was a better teacher than I was; I'd just ask her to pronounce the word "pumpkin" over and over again, because she couldn't quite get it, until we both gave up giggling.

There were the years of violin lessons and sports practices, when she'd dutifully bring my instrument or gym bag to school on the days I forgot them amidst my textbooks and teenage tribulations. From the first violin recital when I was 8 to the last basketball game when I was 17, Haydée was always in the stands cheering me on. I knew there would always be at least one person there to watch me play, even if my parents were both working late.

There was the afternoon I came home to two scary emails, one from the college I thought I was surely going to attend and one from a school to which I had applied as an afterthought. I opened the former, Haydée by my side, and burst into tears upon reading its rejection notice. I wondered aloud where I was possibly going to go, teenage melodrama in full-force. The acceptance note from the second school — which eventually became my alma mater — was not even a fraction as comforting as Haydée's warm, steady embrace.

And then there was the morning of my high school graduation, when my semi-reformed tomboy self had absolutely no idea what to do with my hair. In swooped Haydée to save the day, like any mother would, armed with a curling iron, bobby pins, and a hard-earned degree in cosmetology from her time in El Salvador. I've never received more compliments on my hair than I did that day.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That day, I took a picture with three of my best friends, smiles beaming like we'd just won the lottery. Haydée is in the background of that photo, grinning and looking down — I think I'd given her my diploma to hold onto, like every "here mom, hold this" shove in the movies — and she looks beautiful. Her long dark hair is curled just so around her face, and her makeup is perfect. She'd had a bit of a cough nagging at her, and a touch of pain in her back, but other than that, she was all smiles.

"How is dying ever, at all, acceptable?"

That's the question doctor-writer Atul Gawande posed toward the end of his documentary, Being Mortal, which aired this winter on PBS. Spun out of Gawande's 2010 New Yorker essay, "Letting Go", and his 2012 book of the same name, Being Mortal explores medicine's devastatingly uncomfortable transition from protecting a patient's quantity of life to protecting its quality.

In "Letting Go," Gawande told the story of a young wife who was diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer — a condition modern medicine knows to be terminal — in the ninth month of her pregnancy. At 34 years old, Sara Monopoli had never smoked a cigarette and yet found herself with an inoperable tumor. "There is no cure for lung cancer at this stage," Gawande wrote in his essay. "But it seemed harsh and pointless to confront Sara… with this now." Instead, over the course of eight months, Sara and her husband chose a series of aggressive treatment methods even as each one brought little to no improvement — and much discomfort — until her death in February 2008. No member of Sara's treatment team had truly broached the possibility of prioritizing Sara's quality of life over its quantity.

Four months ago, I lost Haydée to lung cancer. Her story is much like Sara Monopoli's: She too had a cough and back pain that, seemingly out of nowhere, yielded a diagnosis of Stage IV lung cancer shortly after my high school graduation. She too had never smoked a cigarette. She too started treatment with the experimental drug Tarceva. She too was young and had so much to live for. The difference is that Haydée survived nearly five years with this disease — including two and a half years after the cancer had metastasized to her brain.

Haydée defied everything it means to be a 'terminal' cancer patient.

None of this is to say that something Sara Monopoli did (or didn't do) condemned her to a shorter timeline. It's only to emphasize that despite nearly identical medical situations, the progressions for terminal illnesses are never certain. I remember when I saw the piece of paper that outlined Haydée's diagnosis: I saw "Stage IV" staring at me. I felt panic gurgle in my stomach, even though I didn't know for sure what Stage IV meant. I remember desperately typing "lung cancer staging" into Google — the beginnings of that illogical, blind hope Gawande discusses — and seeing the prognosis. I remember crying into my dad's shirt. I remember sobbing into the phone with my brother on the other end. I remember my mom telling me that 50 percent of people with this diagnosis die within six months, and just 10 percent make it to five years.

What I don't remember is the first thing I said to Haydée after she appeared in my bedroom doorway and calmly stated, "I have cancer." That's not to say she wasn't scared — I know she was. But in the years I had with Haydée after she received her diagnosis, I can only remember three times she revealed any true concern for her mortality. Once was during that summer, in the first months of treatment. The other two times were in her final week of life.

In its documentary form, Being Mortal tries to address this conundrum: the moment when a doctor must decide whether reality or fantasy will benefit his patient more. The film interweaves the final months of terminal patients' lives with interviews with their doctors, juxtaposing the medical reality of the patients' conditions with their most private hopes. In the end, it's clear: Gawande finds the fact that doctors (including himself) push false hopes and miraculous recoveries over the realities of terminal illness to be a critical weakness of modern medicine.

I'm sure that Haydée was told in no uncertain terms what her diagnosis meant, practically speaking. I'm also all but certain she chose to largely ignore this information. Instead, she let me drag her to Color Me Mine to paint pottery (twice) when I was desperate to do an activity with a souvenir in case she was all of a sudden ripped from my life. She'd go for daily walks in the Los Angeles heat and spend all afternoon watering the plants and tending the garden, just as she always had, except now with a huge white hat with an oversized brim to protect her skin from the sun. She'd make me lunch and we'd sit down to eat together, except now there were tiny glasses of vegetable juice concoctions she'd been told to drink, one for each of us. She'd entertain all my concerned questions and insistences that I help out with the household tasks, letting me feel useful when I felt totally useless. She never acted as if her days were numbered. And her number far exceeded doctors' expectations.

So here's the thing: When confronted with a young, passionate patient with so much to live for, why immediately dash her hopes? Is it really better to immediately hammer home the imminence of death rather than encourage the hopefulness of life?

One day, while I was home on break from college, I took Haydée to an appointment with her oncologist. He pulled up her most recent brain scan alongside the previous one, and the three of us crowded around the monitor to look. To me, it seemed like the most recent scan's tumor was ever-so-slightly bigger. But the oncologist smiled a warm smile and told Haydée, "You're doing well. I don't see why we can't keep this going."

I trusted the oncologist, despite what I saw in the scan. Haydée shot me a look that said "see, don't worry," and led us out of the building. I followed her, and kept up the only way I knew how to contribute to her treatment: wishing hard on every eyelash and birthday candle and standing between her and the microwave whenever possible in case that radiation myth was actually true.

That appointment was more than a year ago — long before her disease led to the complications that took her life this past December. It's completely possible that the oncologist did truly think the scan was nothing to worry about, and considering Haydée lived for more than a year after he made that declaration, perhaps he was right. But even two days before Haydée's condition suddenly and rapidly deteriorated this winter, while we were in intensive care but things weren't quite so intense, the nurses said Haydée would soon recover. She might need some extra help at home, sure, and maybe it would be good to have some oxygen on hand, but she'd be back on her feet before long.

Now I can't help but wonder: Did the doctors and nurses always know things we didn't? Did they avoid discussing the inevitable, approaching end because, well, they'd given a terminal diagnosis years ago, so what good would it do? And then I ask myself: Am I angry at the nurse who smiled in my face and made me think things would be OK — or am I glad she brought me some comfort in that moment?

I don't know if Haydée understood the reality of "terminal" when she heard it all those years ago. I also don't know if that's a bad thing. She defied everything it means to be a "terminal" cancer patient. And while I do think she would have preferred not to spend the last few days of her life in the hospital, I also know she would've rejected everything it would mean to go home and wait to die when there was more that could be done.

In one of those very rare moments where she belied her worry, Haydée looked at me sitting next to her in the ICU and asked me if it looked to me like she was dying. I said no. I told her it looked like she was getting better and I thought she would be healthy very soon. It was true to me, in that moment: She'd been alert and active all day, cracking the slightly off-color jokes she loved and smiling brightly at her care team. I'd even watched as she practically ran around the hospital floor, pushing the walker along and only stopping her stroll because the nurses told her to. I looked at her and, despite the objective evidence around me — the fluorescent green numbers blaring off machines, the tubes coming and going, the delicate updates from the doctors — I told her I thought she was going to be just fine.

Am I guilty of skirting the truth, just like Gawande says? Probably. But it didn't feel like lying at all. It was what I believed — or wanted to believe, so much so that I didn't see any other way — and it was what worked for Haydée too. Dying wasn't ever, at all, acceptable to her, and I'm proud that she lived that way until the end, and that her doctors allowed her to live that way until the end.

She was my mother, and I can't think of a better role model of grace, determination, and love for me to look up to.

Kimberly Alters is the news editor at TheWeek.com. She is a graduate of the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day