How to turn your embarrassing Google searches into a hack-proof password

From The Idea Factory, our special report on innovation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

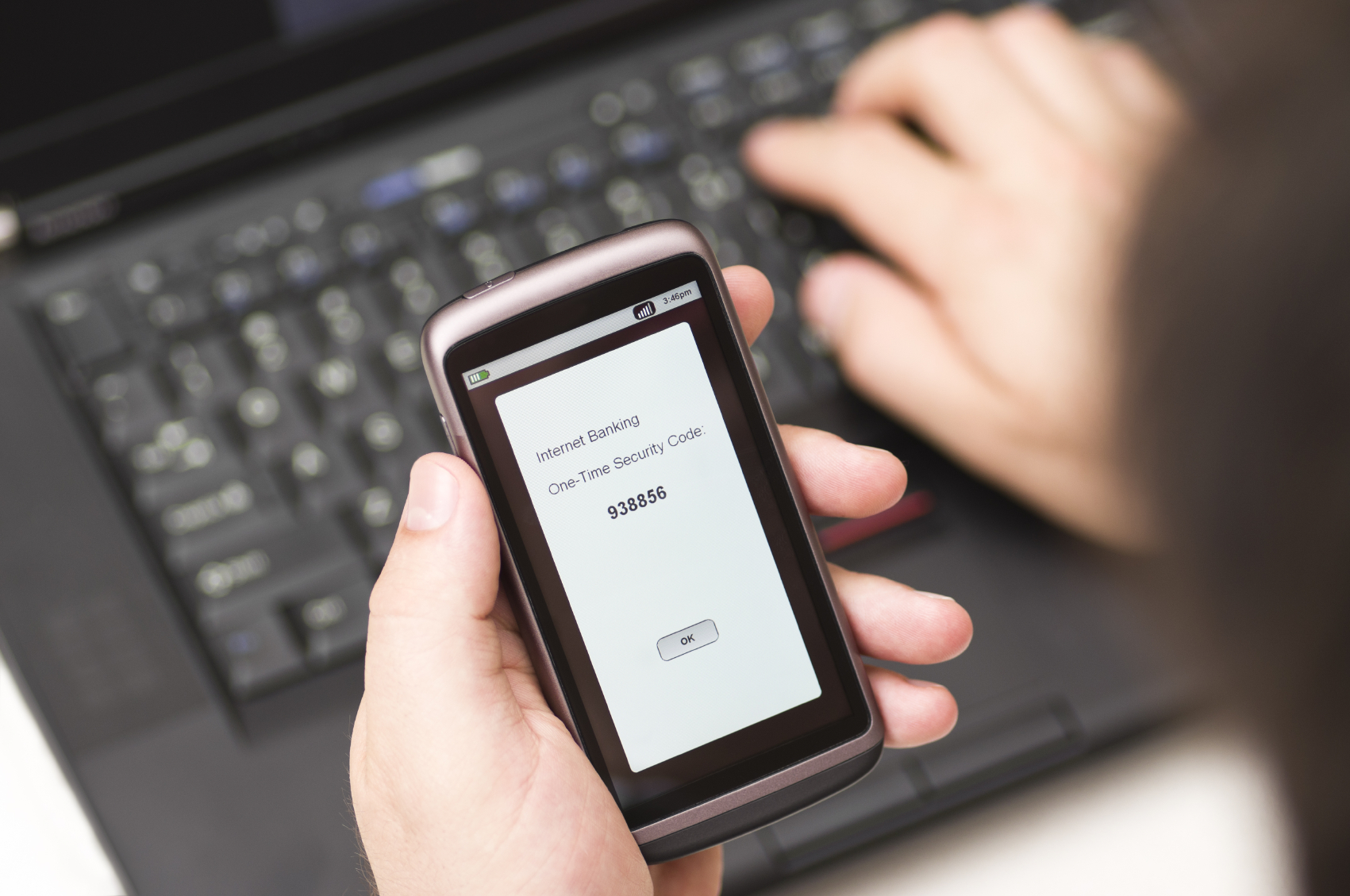

We have a password problem. Each year, millions of our accounts are broken into, and no matter how many times we're told to make our PINs more secure, the most common passwords last year were almost willfully obvious: "123456," "password," and "12345".

There must be a better way.

Imagine if, when logging in to check your email, you were prompted with a personal question like, "What new song did you download yesterday?" or "Who was the first person to text you this morning?"

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Researchers believe this kind of very personalized (and arguably creepy) authentication process could be the future of passwords. Secrets shared only between a user and her devices — like private Facebook activity, or web browsing habits — were turned into very effective passwords in research trials.

"Whenever there's something you and your phone share and no one else knows, that's a secret, and that can be used as a key," Romit Roy Choudhury, an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who co-authored a paper on this topic, told MIT Technology Review.

For the project, called "ActivPass," researchers from Urbana-Champaign, the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, and the University of Texas at Austin developed an app to mine subjects' smartphone activity, along with an algorithm to identify good sources for questions. They found that to serve as an adequate password prompt, events have to be unique enough to jog a user's memory.

And have very short memories. Recall rate of activities that happened one day ago was about 90 percent, and that rate declined quickly to less than 60 percent after about four days. This means password prompts would need to be pegged to very recent events, like that song you downloaded last night, to stand any chance of being effective.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We're also terrible at recalling our own browsing history. "Several users were not able to recall whether they browsed a ‘lsbf.org.uk' website," the study says. "But immediately responded positively when asked if they visited the 'London School of Business' site. As a result, webpage titles and descriptors are needed."

What about security? What are the chances of someone guessing the right answer? The questions would need to be about specific, private behavior, and unrelated to a user's public Facebook profile. The researchers write that "several 'friends' were able to predict, say, that a student of MIT was visiting an alumni group of MIT Robotics."

Overall, the study's socially mined questions worked effectively as password prompts: 95 percent of the time, users answered three questions correctly. On the flip side, and somewhat reassuringly, they were able to answer questions about other people only 6 percent of the time.

Choudhury tells MIT Technology Review that he and his team are currently in talks with several companies, including Yahoo and Intel.

Jessica Hullinger is a writer and former deputy editor of The Week Digital. Originally from the American Midwest, she completed a degree in journalism at Indiana University Bloomington before relocating to New York City, where she pursued a career in media. After joining The Week as an intern in 2010, she served as the title’s audience development manager, senior editor and deputy editor, as well as a regular guest on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. Her writing has featured in other publications including Popular Science, Fast Company, Fortune, and Self magazine, and she loves covering science and climate-related issues.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy