The extraordinary foolishness of building an EU army

This borders on farce. And yet...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Overall, the past 70 years have been very good to Europe.

Yes, there was the Eastern Bloc's somewhat messy dissolution at the end of the Cold War, the Greek financial debacle, and many other crises and tragedies. But compared to the extraordinarily bloody history of the Continent, the last several decades have been dominated by relative calm and contentment.

That peace may be waning. There are several possible reasons, but Russia's recent provocations are chief among them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's why Jean Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission and former prime minister of Luxembourg, declared this spring that perhaps the Continent needed an "EU army" to counter Russia's aggressive posturing. This idea was more recently buttressed by Germany's defense minister, who referred to such a force as her country's "long-term goal." Last week, Juncker doubled down, saying the EU needs an army because "a bunch of chickens looks like a combat formation compared to the foreign and security policy of the European Union."

The need to counteract Putin's influence is understandable. But an army made up of countries that can't agree on where to eat lunch feels very much like an exercise in futility, and may in fact prove counterproductive.

Don't get me wrong. Putin is a real threat. Analysts have long pointed out that Russian meddling in Ukraine may well be a rehearsal for a much larger theater. After all, Putin has already made himself at home in Georgia, far-right parties sympathetic to Russia are established throughout much of Europe, and countries with an ax to grind, such as Greece, may see new possibilities with a very powerful potential ally.

Europe needs to counter this. But the idea of an EU army is the wrong antidote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Any EU-centric defense force would be plagued with the same bitter, nationalistic demons that have haunted the European Union itself since its founding. Like siblings that have lived together too long, the countries that make up the EU are slow to forget the past. Seventy years beyond the last World War, Germany is still reminded of its darkest hour by its dearest debtor.

Thousands of years of European history have carved out rock-solid personalities among nations that are now supposed to look to Brussels — Brussels! — for guidance on their supposed best interest. Imagine Oklahoma City telling Austin how it should handle its influx of immigrants. Then multiply that dissonance by 1 million. That's how people in the United Kingdom feel about bailing out Spain.

If the economic crisis of 2008 taught us anything, it's that the countries of Europe have a very difficult time loaning each other money. Standing in solidarity at the end of a superpower's barrel seems like more than a stretch. And it's particularly absurd when you consider that the European countries that could actually finance and supply the muscle necessary to rebuff Putin have nothing to gain and everything to lose.

Britain, Germany, and France lead the EU in defense spending, and their national security concerns are far removed from those of Poland and Romania. Despite the fall of the Soviet Union and the (perhaps temporary) westward turn of former Eastern Bloc countries, the alienation and distrust formed during much of the 20th century hasn't just disappeared. The Cold War lasted far longer than it has been over.

If austerity nearly toppled the EU, a war with Russia would likely obliterate it. It's hard to imagine a family from Lyon smiling and waving as their son is sent off to battle in South Ossetia. The cultural canyon between the two is far deeper than the one that separates, say, Alabama and Alaska.

But perhaps the greatest threat posed by an EU army is one endemic to all large, ill-conceived institutions: bureaucracy. The EU's current defense forces, known as battlegroups, require agreement among all 28 member states to be deployed, hence their never being deployed. It's impossible to imagine a scenario in which every EU member votes "yay" to war with a nation that is one of the region's largest suppliers of oil and gas.

But let's imagine that logic be damned, the continent follows through on an EU army anyway. (It wouldn't be Europe's first bad idea.) The damage to the EU's relationship with NATO, the one organization that is actually capable of countering Russian interests, might be irreparable. If the EU wishes to avoid another Cold War, it would behoove Brussels to stand in solidarity with the organization that won the last one.

America and England have the largest and fifth largest defense budgets in the world, respectively, and have a proven track record of putting Russia in her place. Diverting resources from the world's most powerful military alliance to the formation of an infantile fighting force that has never fired a single shot defies logic, to put it mildly.

The fear of Russian hostility following Putin's unchecked aggression is justifiable, as is rhetoric to reassure a continent rumbling with the prelude to conflict. But this isn't Luxembourg, Juncker's homeland where he commanded all of 900 troops. And this isn't the Germany of old, with one of the world's premier militaries. This is Russia and the Western world; the stakes are too high for fantasy.

Greg Jones is a freelance writer who covers technology and politics.

-

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTU

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTUIN THE SPOTLIGHT How does the party out of power plan to mark the president’s first State of the Union speech of his second term? It’s still figuring that out.

-

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanches

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanchesThe Explainer Several major ones have recently occurred

-

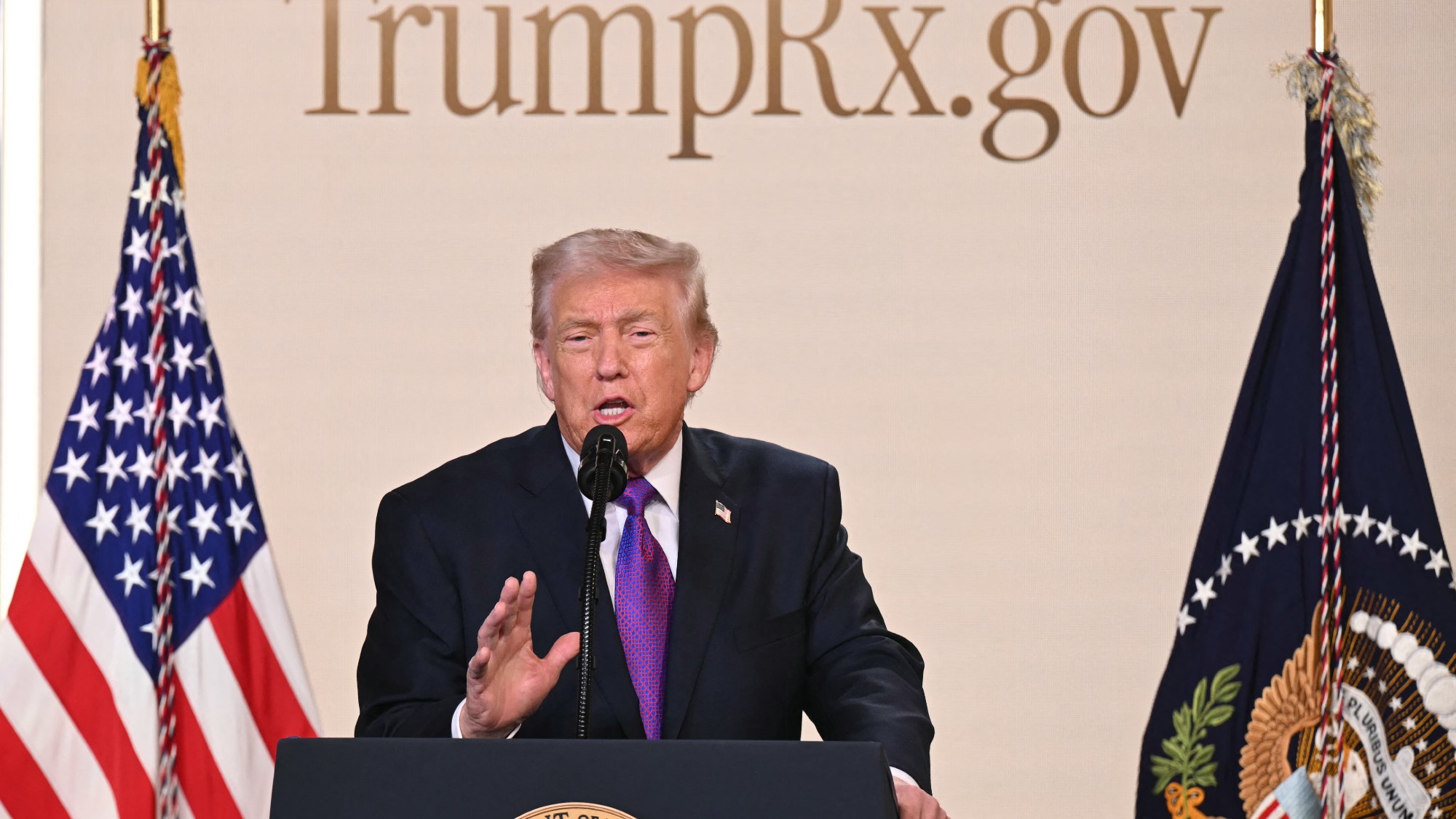

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?The Explainer The new drug-pricing site is designed to help uninsured Americans

-

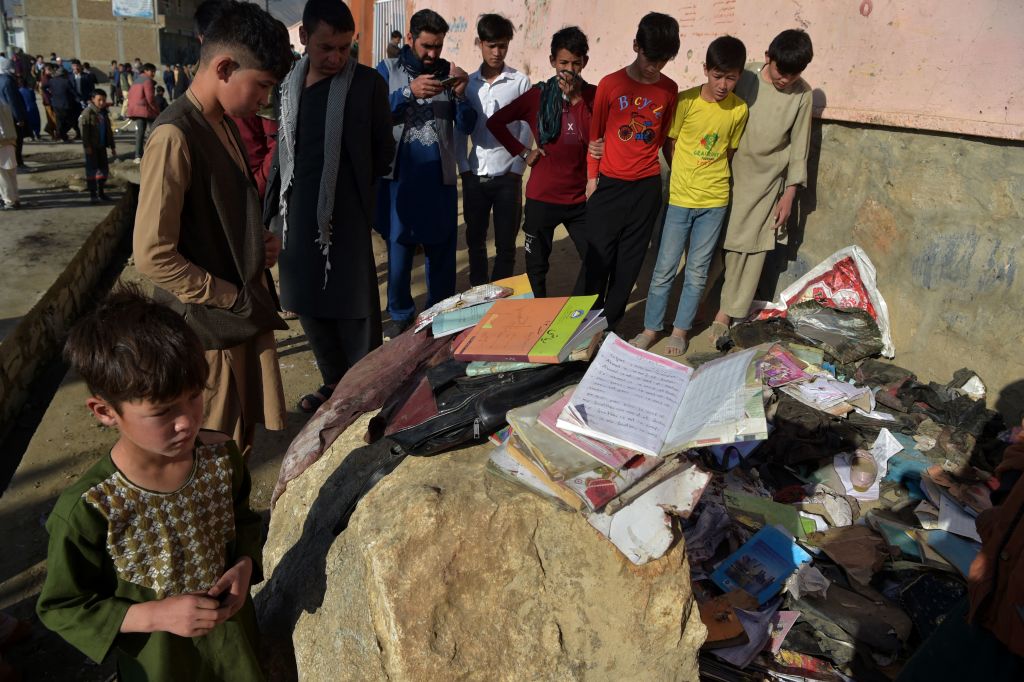

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

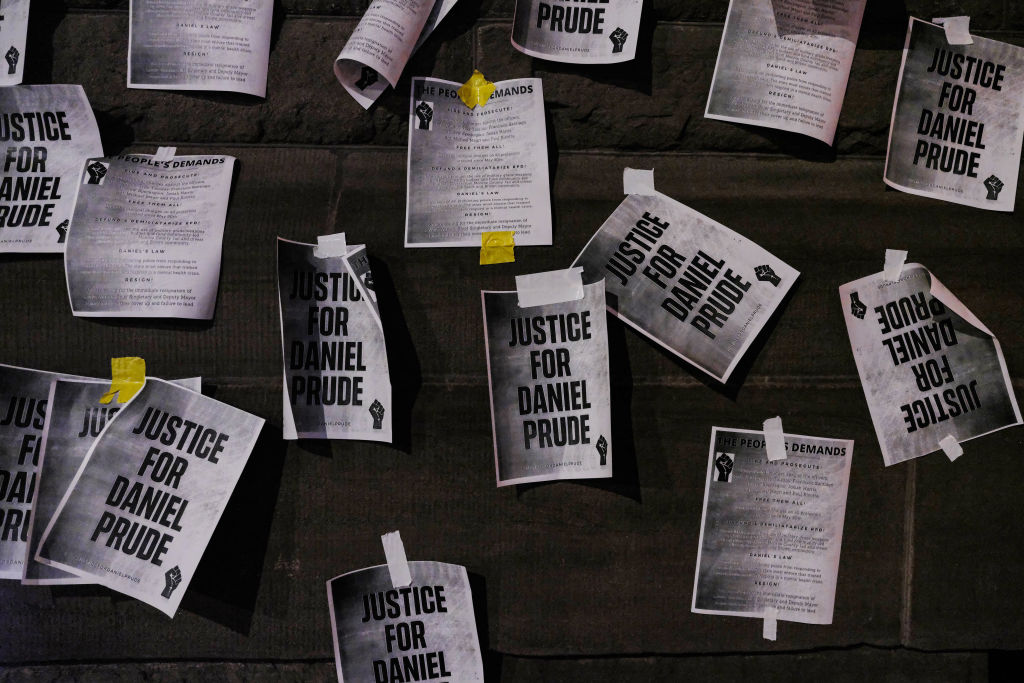

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

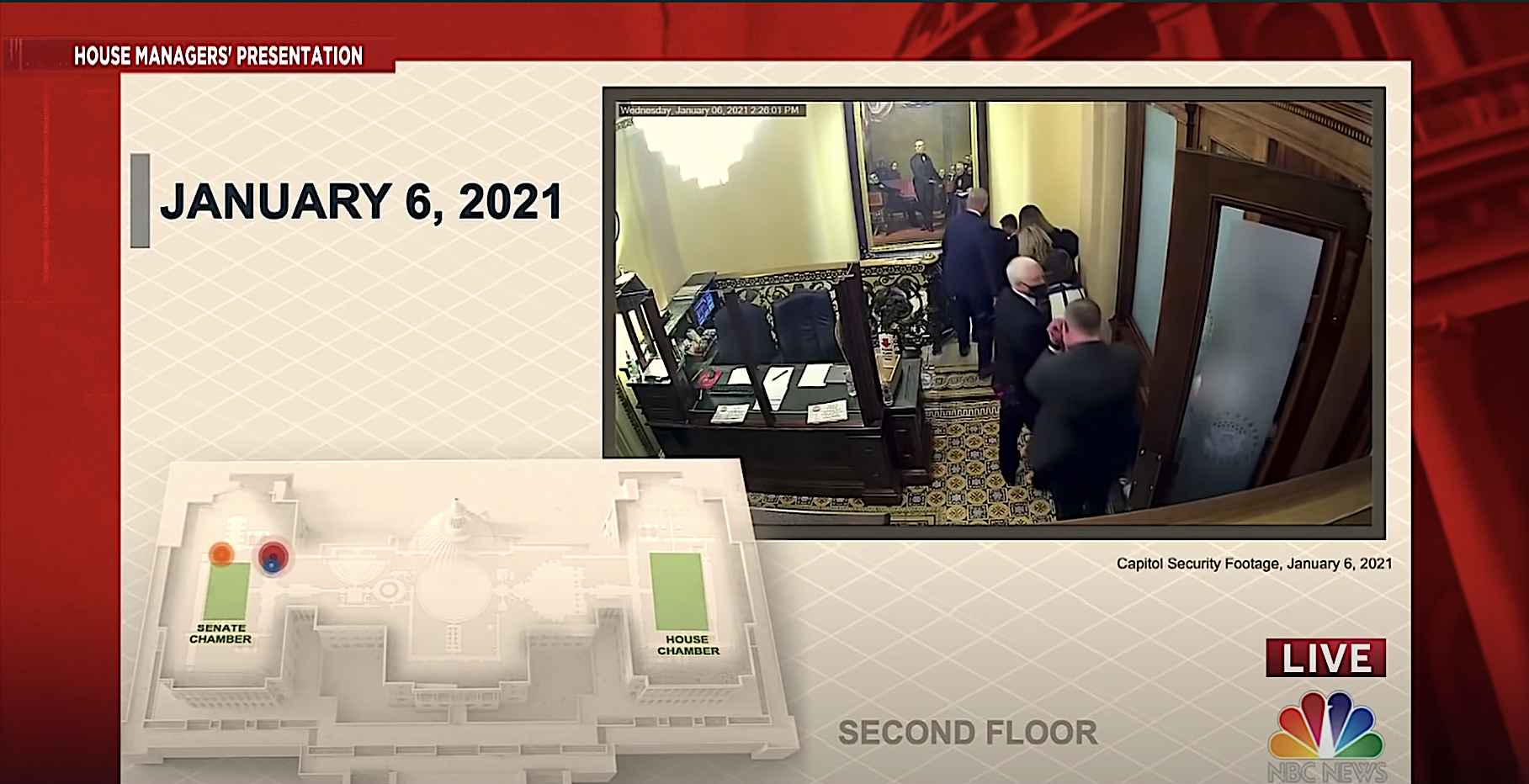

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read