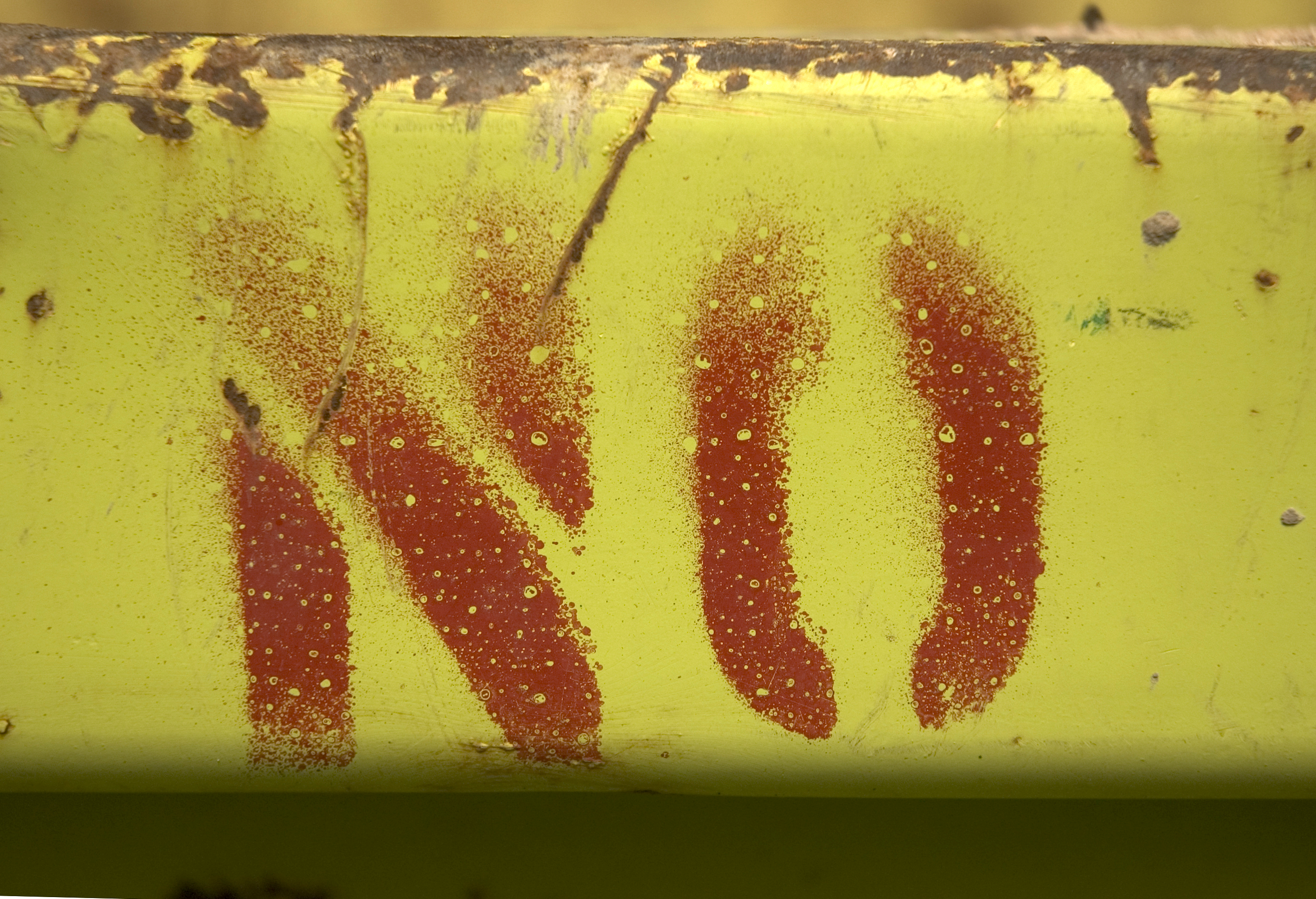

Why 'no' is the most powerful word in your vocabulary

It feels great to say yes. But it's often better to say no.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I know this guy — let's call him Dennis — who is universally adored by his very large circle of acquaintances. It's easy to see why: Dennis is smart, personable, and kind. His work ethic is extraordinary. Dennis possesses great charm and the kind of infectious energy that makes everyone around him feel motivated and inspired.

Dennis, however, isn't as successful as he'd like to be, either personally or professionally. He can't seem to move past the first few dates with interesting men he meets, and he's seen numerous promotions in his agency go to colleagues without a fraction of his natural abilities or grit.

So Dennis is also frustrated.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"I never turn down a work assignment or an invitation," he told me recently. "I'm 100 percent there, 100 percent of the time. So why can't I catch a break?"

Then there's "Kiana." Kiana enjoys a reputation as something of a superhero, because there seems to be nothing she can't do: juggle a successful dermatology practice and two happy children, chair the local elementary school fundraiser, and coach soccer. She loves to cook, is active in her church, and entertains frequently. Everyone admires Kiana, including her devoted husband.

But Kiana isn't entirely happy, either.

"I'm pretty tired and down most of the time," she admitted to me recently. "I wonder if I need to go on antidepressants?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Neither Dennis nor Kiana needs drugs or better luck; what they do need is to learn how to more strategically manage access to themselves and their resources. In short, they need to not always be quite so available to others. But that can be hard when so many factors compel them — and all of us — to "be there" at every opportunity.

Our inclination to be available and helpful is rooted in sound survival strategy that dates back to our earliest days as humans. Back in the day, you basically had two choices: Try to make it on your own — hunting and gathering and finding shelter and maybe (if you were lucky) a mate — or pool resources with a like-minded group of fellow hominids and divvy up the labors associated with staying alive and passing your genes on to another generation.

You can guess which strategy proved more successful over time. By extrapolation, you can further assume that individuals within such successful groups who proved themselves more generally useful enjoyed greater success within the group. (Hey, Gronk, would you be willing to slog 20 miles through Ice Age mud to bring back a mammoth or two for the rest of the cave to snack on this winter? Yes? All right! Here's the best spear we've got. Also, you can marry my daughter when you get back.)

Notwithstanding anomalies like Attila the Hun and Donald Trump, nice, cooperative people have historically done better than mean, selfish ones. It's just in our genes.

I once had a friend who was running for public office ask me — in a meeting, in front of others — to chair his campaign's finance committee. I had many good reasons to decline this request and was about to do so — respectfully — when he laid a hand on my arm and said, "We need you. This campaign needs you."

The "no" died on my lips as I processed that. Ramon was a proven public servant whose candidacy for an important office had the potential to positively affect people and issues about which I care passionately. How could I not step up when I was so clearly needed? Fortunately for me (and my family, my career, and my sanity) someone else far better equipped volunteered at that point and spared me what could have been a disastrous choice.

You've surely been there, too. The Shakespeare Ensemble can't attend Edinburgh this year unless you agree to go along and chaperone 16 teenagers...We aren't going to make our third-quarter goals unless you come in this weekend and close some extra sales...Daddy, I need to go to school dressed as Abraham Lincoln. Tomorrow. One quarter of my grade depends on it.

Responsibility is a heavy cross to bear, especially when you really can't or don't want to do something.

And let's face it: It's flattering to be in demand. When the person organizing the Glee Club Bake Sale tells you your Snickerdoodles are the only item that sold out last year, your pride pretty much dictates you volunteer to whip up another batch, even if you're short on time and butter. When your boss asks you to lead the team tackling a website redesign for a major client, she's singling you out as "the one" among many. That feels so good you might just jump at the opportunity, even though you know your current workload won't allow you to do your best work on this project.

Pride makes it hard to say "no," even when we know we should. Just remember pride also goeth before the falling of all those balls you are going to drop when you over-commit.

Avoiding the automatic "yes" can, paradoxically, help you achieve more, meet higher standards, and make people respect you more.

Let's take another look at Dennis. Dennis makes it a point to be "100 percent" available, both at work and amongst his friends. This readiness to always be there — to return texts and emails 24/7, always stop and chat, do a favor, give a ride if needed — is one of the reasons people like him so much. Unfortunately, they don't always respect him, or his time.

So Dennis is perennially late. To everything. (Those of us who know him well refer to "real time" and "Dennis time.") Because he's doing so much, he often forgets things he's promised to do. Despite working long hours, Dennis often misses deadlines, and his supervisors say he lacks attention to detail. So do potential boyfriends — most of the guys Dennis dates get fed up with the chronic tardiness and scatter-mindedness.

Then there's Kiana. Unlike Dennis, Kiana is perceived by others to be extremely competent — so competent, in fact, that they are perfectly happy to sit on the sidelines and tap her to assume responsibility for anything and everything. Need to get something done? Call Kiana. She's a superhero.

Because Kiana selflessly makes herself so available, others take her for granted. No wonder she's depressed.

Being available — saying "yes" — is a great way to build alliances and get things done. However, when others perceive you as always on-tap, they actually value you — and your time, money, and energy — less. Strategically manage how you allocate these things, and you will find yourself more appreciated, less stressed, and potentially more successful than you imagined you could be.

Leslie Turnbull is a Harvard-educated anthropologist with over 20 years' experience as a development officer and consultant. She cares for three children, two dogs, and one husband. When not sticking her nose into other peoples' business, she enjoys surfing, cooking, and writing (often bad) poetry.