The chef who saved me

I met Jacques Pépin during one of the worst weeks of my life. It was a lunch I'd never forget.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IT HAD BEEN a bad breakup. She and I had lived together for three years, long after it was clear we had been a mistake from the beginning. There followed, finally, a kind of plummeting death-lock in which she and I could do nothing but cleave together and grimly wait for the ground to arrive.

It left me living in the windowless basement of an old friend's house in Brooklyn. Mornings, I lay in the complete darkness, listening to the shuffling and creaking as he and his wife and two children prepared for the day. There had been a time when I'd still felt close to that domestic future, but now the truth of my life had been revealed: I was no man. I was a troll in the cellar.

Of all the fallout — physical, psychological, and emotional — one effect was most worrisome: I had lost my appetite. Believe me when I tell you that this never happens — not when I'm sick, not when I'm sad, not when I'm busy. I do not understand when people "forget to eat." Now, though, my stomach was wound so tight that there seemed to be no room for food.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Just by way of topping things off, I was broke. Which is why, though I felt incapable of forming a coherent thought, much less writing one, I accepted an assignment from a sympathetic friend at GQ. It was a short sidebar, to be included in a package about home cooking: Ask Jacques Pépin, one of the world's first celebrity chefs, for his tips on designing a home kitchen.

I'm embarrassed now to admit that I was only dimly aware then of who Pépin was. I knew he belonged to the pioneering generation of food personalities that predated the current celebrity-chef revolution. But I did not overly prepare for this interview.

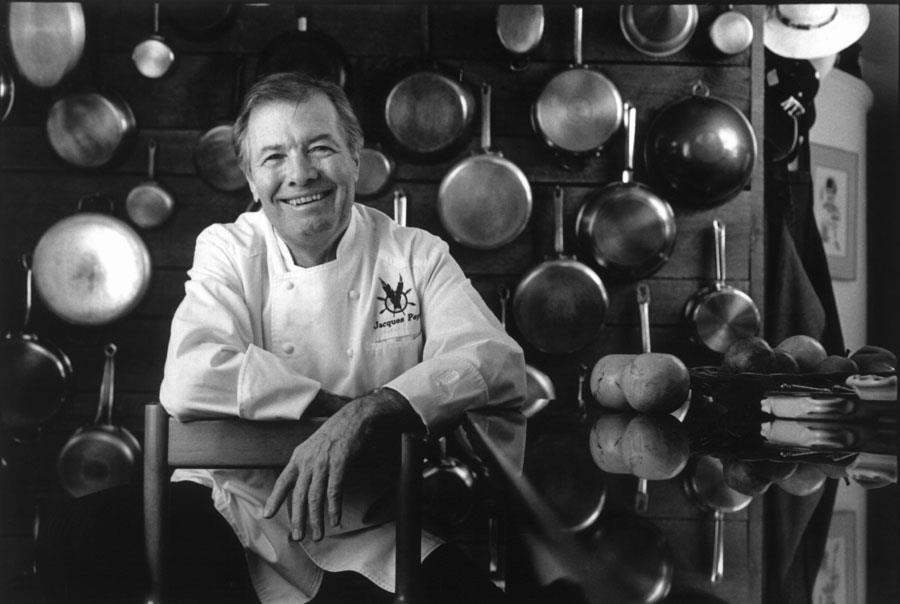

I knew enough about Pépin's stature, however, to feel sheepish about taking up his time for such a small story. I expected to spend a quick 20 minutes at the International Culinary Center, where Pépin had been dean since 1988. An assistant led me to the cluttered office where Pépin waited. He was wearing chef's whites, having just given a demo to students in one of the downstairs kitchens. He extended a hand to shake, one of the most extraordinary hands I'd ever seen. It seemed at once wrecked by years of kitchen work and oddly delicate; the hand of a workman and an artist. I shook it hastily and muttered an apology for taking up his time.

"No, no. Don't be ridiculous," he said. His accent was almost comically French, despite nearly five decades in the United States.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I settled in, and we talked about the finer points of kitchen design. How one should have a gas stove but opt for the consistency of an electric oven. How a side-by-side fridge and freezer is a waste of space and the freezer as bottom drawer is preferable. How most gadgets are useless. How there should be good light, good music, and a good view, if possible, and a place for your guests to perch to drink wine and watch you work.

What I noticed most was how completely Pépin was granting me his attention, how present and engaged he was, despite the banality of my questions. Twenty minutes passed quickly, then 40, then an hour. I was aware that my shoulders were starting to relax.

It was now approaching noon, and finally I got up to leave. "Would you like something to eat?" Pépin's assistant asked. I assumed this was just a courtesy and prepared to beg off. "Will you join me?" I asked Pépin, sending the courtesy back.

He looked at me as though I might have hearing problems. "Of course," he said. "It's lunchtime!"

WE TOOK THE long way downstairs, so that Pépin could walk me through ICC's facilities. Every time we entered a kitchen classroom, the young men and women in their starchy whites and toques would stiffen over their cutting boards and mixers, stealing glances at Pépin. He did his best to put them at ease, laying a hand on a shoulder and offering bits of advice.

At L'Ecole, the ICC's student-manned restaurant, we were ushered to a seat and given menus. Pépin ordered a bottle of Sancerre. Conversation came easily. We talked about his arrival in New York, in 1959, a time when it was possible to land in town and, within weeks, know everybody who mattered in the food world. Pépin had done just that, quickly meeting such legendary figures as James Beard; Pierre Franey, chef at Le Pavillon; New York Times restaurant critic Craig Claiborne; and Julia Child, whose Mastering the Art of French Cooking was still a pile of typewritten pages.

The food came and I took a few tentative sips of consommé. "What do you think?" Pépin asked. This was not a test, but genuine curiosity. I said it was good but could use some salt. He reached over and took a spoonful. "I think you are right," he said.

I was pleased, but I had not told the whole truth. Yes, I thought the soup needed more salt. But I also thought it was the most delicious thing I had ever eaten. I was aware, as more food arrived, that I had started breathing for what seemed like the first time in weeks. And I was ravenous. I grabbed hunks of bread and slathered them with pâté, wolfed down delicate, pink lamb chops, gnawing the bones. If Pépin noticed, he didn't say. We reached over to each other's plates to take tastes, ordered another bottle.

I sat in a state of wonder. At a time when I had forgotten the possibility of pleasure, Pépin had effortlessly, instinctively brought me back to life. Without knowing it, he had extended a hand to a drowning man. For dessert we had crème brûlée and an apple tart, coffee, and one more glass of wine. And then I was shaking that hand again, the other clasped warmly atop mine. And then I was out on the street, dazed and floating.

I made it through that summer, slowly rejoining life. I had another relationship. Later, I wrote a couple of books. In 2011, I got on a train and moved to New Orleans, where, eventually, I bought a house with the woman I intend to spend the rest of my life with. We built a big, open kitchen, with space for stools at the counter and a freezer stacked underneath the fridge. I became a father.

Along the way, I've cooked an awful lot from Pépin's cookbooks: squab with lettuce, roast leg of lamb, leafy salads with mustardy vinaigrette, and boiled potatoes.

I learned quite a bit more about Pépin the man, too. His has been a life too varied and rich to be quickly summarized: from apprenticeships in the provinces, to the kitchens of Paris, to the palace itself, where he served three prime ministers, including Charles de Gaulle. He made the fateful passage to New York, where he landed in the kitchen of the legendary Le Pavillon. He met Craig and Jim and Julia. And he fell in love with America — with Oreos and Jell-O, Maine lobster, fried chicken, sweet summer corn, and Reuben sandwiches. With the country's democratic, openhearted approach to food. His accent may be Pepé Le Pew's but his heart is pure Capra.

YEARS LATER, I'M back in front of the ICC to take up more of Jacques Pépin's time. It amazed me, the more I thought about it, that it had never occurred to me to simply reach out and say thank you.

I was invited to watch him give a demo at the ICC and then have dinner. To answer my first question: I did look familiar, though he couldn't remember exactly why we had met. "It was silly," I said. "A waste of your time."

"We had lunch, didn't we?" he said. "So I was not suffering."

We sat at a table at L'Ecole, a few feet from where our first meal together had been. Pépin ordered some wine and bread, charcuterie, and homemade cavatelli with rock shrimp and two whole Fourchu lobsters — a special variety found only in the cold waters around an island in Nova Scotia.

We talked about the state of modern chefdom. He was clear-eyed but uncranky. The undercooking of everything, especially vegetables, drove him crazy. So did excessive culinary piety: "I've been in restaurants where they bring over a carrot and say, 'This carrot was born the ninth of September. His name is Jean-Marie...' Just give me the goddamned carrot!"

I was stalling. Twice I opened my mouth to tell my story and twice I was surprised to find my heart beating wildly. The lobsters came and Pépin used two hands to pry open the shell with a resounding crack. I took a deep breath.

"So, the reason I came here today," I began, "I wanted to tell you a story about the last time we met and...for reasons...there's no reason you should have known this, but it was a difficult time in my life, I was at a real low point. I was in a terrible state of anxiety and unhappiness and...I had stopped eating. And, well, it was just such a lovely day that it really turned me around." This was inadequate in the extreme, but apparently my tremble did a better job of conveying the depth of my feeling.

Pépin put down his lobster. He dipped his napkin in his water glass and used it to wash his fingers.

"Well, thank you very much," he said, finally. "But I just happened to be there. I was...what is it, from Aristotle? I was just the medium."

"I never said thank you," I said.

"But it was not me, it was you," he said. "You did it."

At that moment, another woman came over to shake Pépin's hand, giving me a chance to collect myself. As simple and obvious as Pépin's assessment seemed, it confused me. I felt both giddy and queasy.

When the woman left, Pépin sat back and took a thoughtful sip of wine.

"I think I know what you are talking about," he said. "After my years in Paris in the 1950s, reading Camus and Sartre, I am a bit of an existentialist at heart. I think that the point is that you do things in life where you are moving...often without realizing it."

He knew what it was like to meet somebody who changed your life. For him, it had been Claiborne, the first food critic at the Times — the inventor, really, of modern restaurant criticism — and a guru of the nascent food scene of the 1960s. Weekends at Claiborne's house in the Hamptons were long parties filled with food and drink, in which guests came and went and ate and cooked. To a buttoned-down Frenchman, it was a revelation.

"In France you would invite someone for the weekend or for dinner, it was an ordeal, but here it was such a free, casual way, an open way of seeing people," he said. "It changed my life. It made me stay in America. I..." He searched for the words. "I came out of my carapace."

We turned to our lobsters and ate, silent for a few minutes, except for the cracking of shells and sucking of flesh.

I realized that, rudely, I hadn't asked what the past six years had been like for him. Not much, he said: A couple of shoulder and hip surgeries, another cookbook. A grandchild. His mother, close to 100, was still alive in Lyon. His poodle, Paco, loved him ever more each day. He and his wife, Gloria, had now been married for nearly 50 years.

Suddenly I was seized with the urge to spill more: "I've tried, Jacques," I wanted to say. "Honestly I've tried. To live with an open heart. To give more than take. To work joyfully. To be awake to the world always. To live up to our lunch. But, it's hard. And I fail all the time."

What I said instead was, "I've tried. Over and over. But...I just can't debone a chicken."

"Ah, well," he patted my arm. "That's probably OK, too."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in GQ. Reprinted with permission.