Why the American military is so hot on laser weapons

The future is coming at the speed of light

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From hand-held blasters to planet-destroying death rays, laser weapons are a fanciful staple of science fiction. But at their core, lasers are just concentrated beams of light that generate heat. As simple as that sounds, they've proven remarkably difficult to weaponize. Until now.

Quietly and without great fanfare the laser weapon has arrived, and warfare will never be the same.

This week Lockheed Martin, the defense contractor behind the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, announced it was exploring ways to put a laser on the controversial fighter. The U.S. Navy has already fielded a laser weapon on the USS Ponce. And the U.S. Army is looking for ways to use lasers to protect troops in the field from artillery shells, missiles, and drones.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

All of this is just a start. As lasers grow smaller and more compact, eventually they will be mounted on everything from bombers to tanks. A quiet killer at the speed of light, lasers may some day dominate the battlefield as we know it.

A laser inflicts damage with heat produced by focused light. This heat can burn a hole in the skin of airplanes, set a pickup truck's gas tank on fire, and even burn holes in people. Pointed at an artillery shell in flight, a laser can heat the shell until the explosive inside detonates.

Engineers have known how lasers work for decades but have been held back by various problems, chief of which are power generation and storage. A laser needs a lot of energy — in the tens of kilowatts range or higher — to be usable as a weapon. And it needs it instantly.

Despite the technological hurdles, there are reasons why research has persisted. Lasers have many advantages over conventional projectile weapons. A laser moves at roughly the speed of light, or 186,000 miles per second. Unlike a missile, an accurate laser beam can't be avoided. Lasers aren't affected by strong winds and can't be blown off target.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Laser weapons are invisible, operating at an optical wavelength the human eye cannot discern. They are also silent and unlike bullets and shells, do not produce miniature sonic booms. Unlike conventional weapons, which utilize a controlled explosion to generate energy, lasers have no recoil.

Lasers are also affordable. A single Griffin short-range missile costs at least $115,000. A shot from a laser costs usually costs less than a dollar, the price of the energy used. The actual laser system is more expensive — the laser on the USS Ponce cost $40 million, including six years of research and development — but expect the price tag to fall as they become more common.

These futuristic weapons do have their drawbacks. They are complicated, delicate systems that generate a tremendous amount of heat and need to cool between shots. The farther a laser travels through the air the weaker it becomes. Particles in the air such as dust, water droplets, sand, or snow can scatter the laser beam, quickly reducing its power.

There are few ethical problems with laser weapons. Lasers appear to be just as humane — or inhumane, depending on how you look at it — as any other weapon. Where users like the U.S. military might run into trouble is if a laser is mounted on a drone, but in that case, like other drone-mounted weapons, it's the ethics of drone warfare up for debate and not the weapon mounted on it.

Laser weapons are rapidly entering service. The U.S. Navy believes it could have a plan to equip the fleet with lasers by 2018. The U.S. Air Force has issued a challenge to the defense industry to put a laser weapon on AC-130 gunships by 2020, and there is consideration toward putting them in B-1 and B-2 bombers.

It's difficult to say what the broader implications are of the laser battlefield, from operations against terrorists to full-scale conventional war. We may be entering an era where everything and anything can be shot down, with implications for the future of manned aircraft. This may push future forces to be even quicker and more agile. Today it's one thing to be targeted and another to be hit; in the future being targeted and being hit will be the same thing.

Whatever the implications are, the U.S. military wants to find out first.

Kyle Mizokami is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Daily Beast, TheAtlantic.com, The Diplomat, and The National Interest. He lives in San Francisco.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

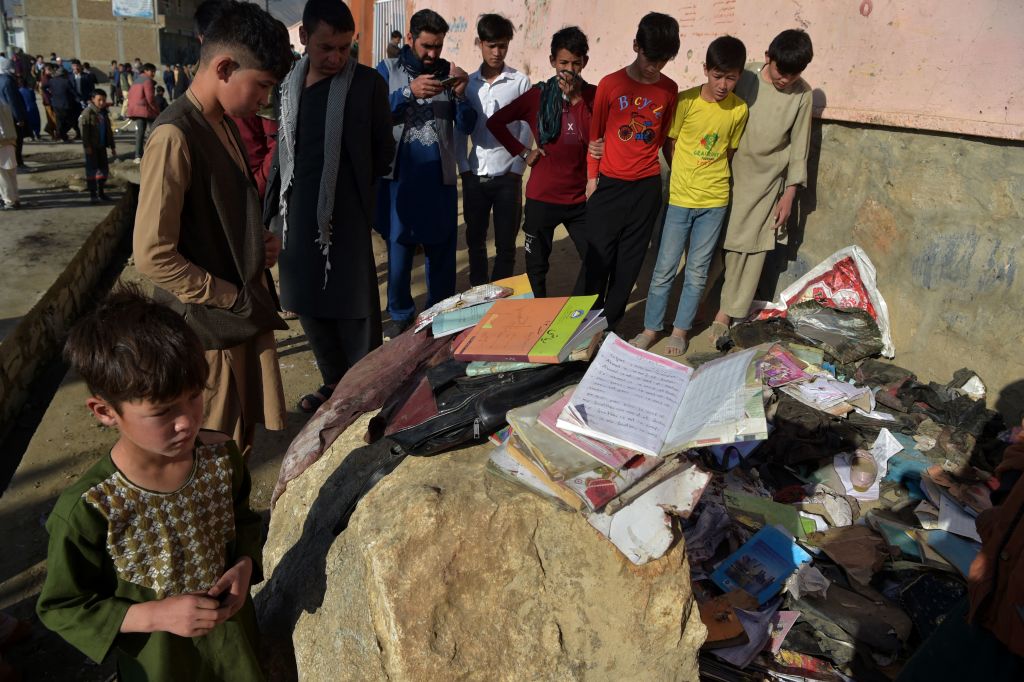

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

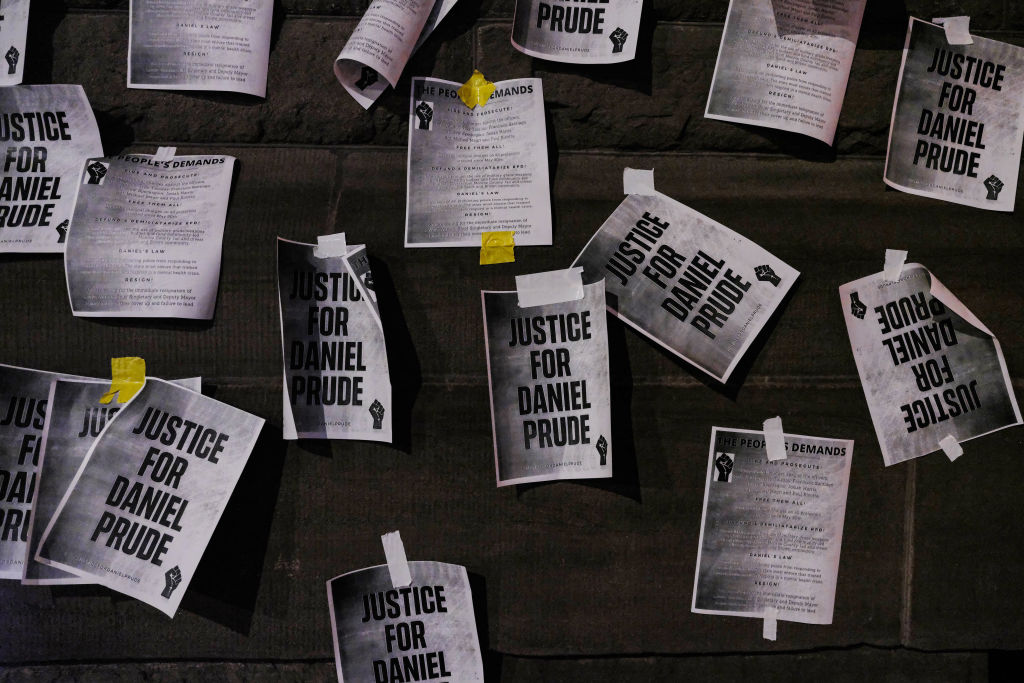

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

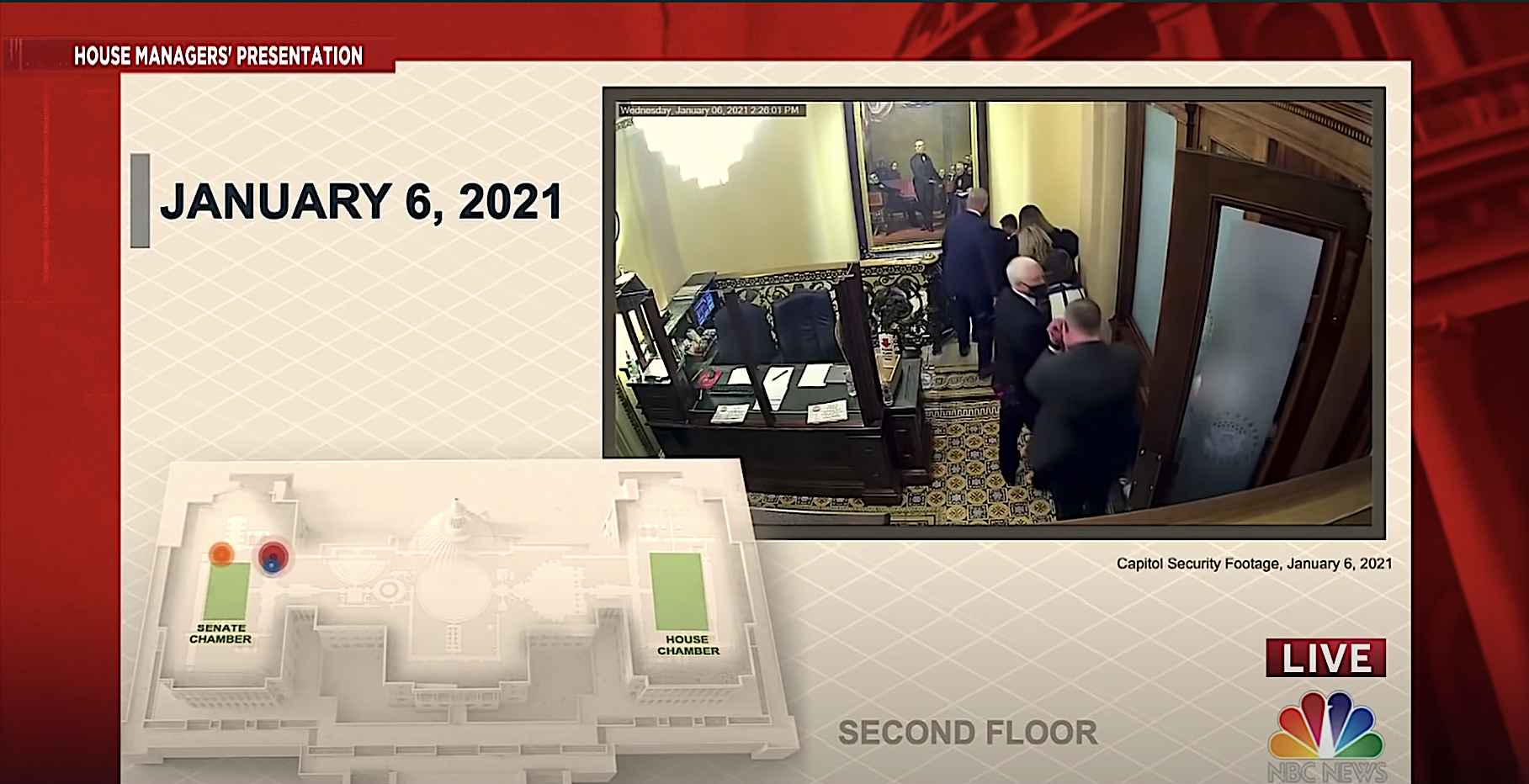

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read