Meet the cyborg plants of the future

Your garden is going to get a lot smarter

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Your garden is going to get a lot smarter.

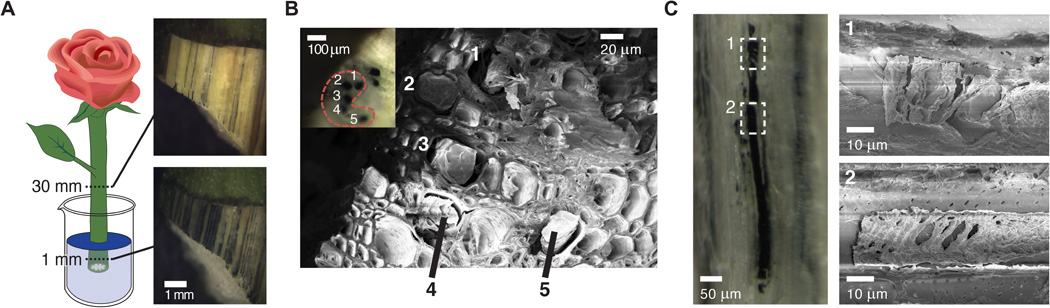

Researchers at the Laboratory for Organic Electronics at Linköping University in Sweden have created cyborg roses by inserting tiny electronics into the plants' vascular systems. Why would anyone want to corrupt one of nature's most beautiful flowers? The scientists believe their research, outlined in a recent paper in Science Advances, could allow us to better understand and even control how plants grow, producing more resilient plants without relying so much on chemicals or genetic modification. All of this has large implications for agriculture.

Here's how it works: The researchers gave the roses a synthetic polymer, which the flowers absorbed in the same way they would suck up water. Once inside, the polymer formed wires that can conduct electricity without interrupting the flow of water and essential nutrients. This lets the researchers tap into the electricity that runs through the rose and create circuits.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"The experiment opens the door for electronics that can plug into plants," writes New Scientist. "The team used the xylem wires to make a transistor — a basic building block of computing and electronics. They tacked gold electrodes and probes along the length of the plant, then connected it to an external resistor and ran a current through it."

Today, our go-to method for controlling how a plant grows and thrives is exposing it to chemicals or altering it genetically. There could be a better way, but as the paper points out, researchers still have a lot of unanswered questions about plant biology, which makes it hard to come up with new, more efficient, and perhaps safer methods. Electronic plants could be filled with sensors and keep track of their own internal workings, relaying the information back to researchers. Perhaps someday a farmer could flip a switch that tells his crops not to bloom before an incoming frost.

"Changing some traits, such as flowering time, may be too disruptive to an ecosystem if done permanently, especially if those changes could propagate through forests and fields," writes Tia Ghose at Livescience. But the researchers say electronic commands could be reversed to prevent that from happening.

There are a lot of hurdles, of course, and this technology has a long way to go before proving practical. For example, if these circuits were to be used in edible plants, researchers would have to prove they don't harm the final product, and guarantee they wouldn't unexpectedly appear on anyone's dinner plate. Also, as Rachel Feltman at the Washington Post points out, these experiments were done on plants that had already been cut, "so it's not clear how long the bionic flowers would be able to bloom with their electronic components in tow."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jessica Hullinger is a writer and former deputy editor of The Week Digital. Originally from the American Midwest, she completed a degree in journalism at Indiana University Bloomington before relocating to New York City, where she pursued a career in media. After joining The Week as an intern in 2010, she served as the title’s audience development manager, senior editor and deputy editor, as well as a regular guest on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. Her writing has featured in other publications including Popular Science, Fast Company, Fortune, and Self magazine, and she loves covering science and climate-related issues.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years