What Apple revealed about the surveillance state's big weakness

What happens when the government isn't a big customer?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

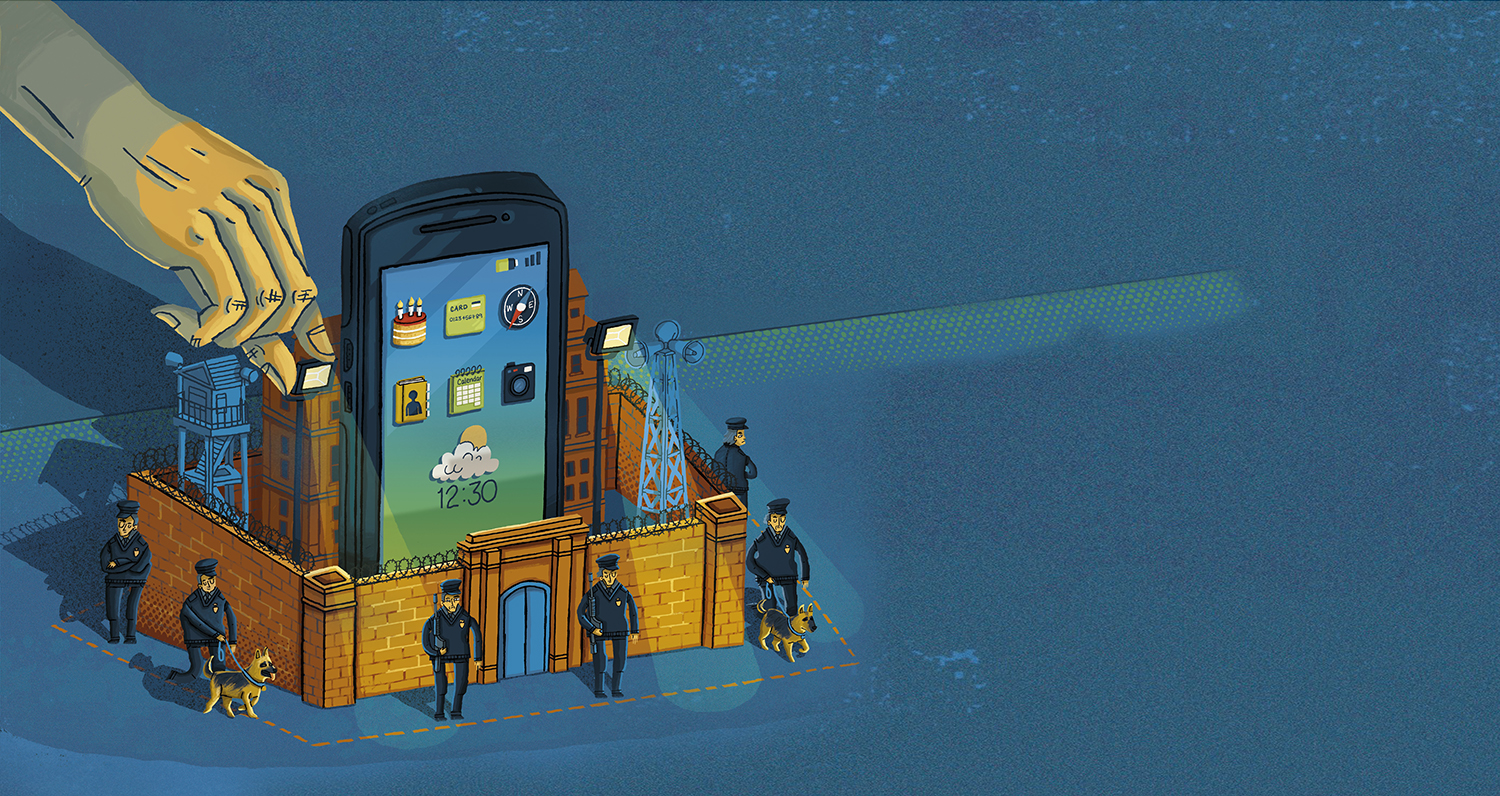

Modern technology has long made for an uneasy coexistence between American business and American government. And on Tuesday, the FBI chose to pick a legal fight with Apple that could upend that already fraught relationship.

There's also a hidden irony: Libertarians and fans of limited government will no doubt cheer Apple's refusal to comply with the surveillance state. But one of the reasons tech companies often acquiesce to government pressure is something else cheered by limited government fans: lower government spending and a reliance on the private sector.

First, the details of the case: Back in December, two shooters killed 14 people in San Bernardino, California, and the FBI has one of their iPhones. The agency wants Apple to install specially designed firmware — the software that runs the guts of the device, as opposed to the software for the apps and music and such that everyday users can fiddle with — just for that iPhone, which would allow the FBI to quickly and easily break through its privacy and encryption protections.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Apple CEO Tim Cook penned a blistering public letter explaining the company's refusal to comply: Once a version of this new firmware is created, it's out there in the world, with the potential it could be stolen, replicated, and reused where it wasn't intended.

On top of that, the court case itself could set a "catastrophic" precedent, as Nicholas Weaver, a researcher with the International Computer Science Institute in Berkeley, explained in a blog post.

The same logic behind what the FBI seeks could just as easily apply to a mandate forcing Microsoft, Google, Apple, and others to push malicious code to a device through automatic updates when the device isn't yet in law enforcement's hands. [...] Foreign universities, energy companies, financial firms, computer system vendors, governments, and even high net worth individuals could not trust U.S. technology products as they would be susceptible to malicious updates demanded by the NSA. [Lawfare]

In other words, if the FBI wins its court case against Apple, it could set off a chain reaction that lumps all devices sold on American soil into a kind of pariah class on the global market.

So you'd expect other Silicon Valley firms and major tech companies to come out of the woodwork in Apple's defense. But they haven't. Google mumbled something about how this "could be a troubling precedent." A coalition to reform government surveillance put together by Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook released a statement that didn't mention Cook's letter, but did say companies shouldn't be required to put "back doors" into their products. But Amazon, Microsoft, Twitter, and Facebook all demurred from commenting directly.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If you dig through the reporting, one big reason the other companies may be skittish is because of another big entanglement private enterprise often has with public government: Namely, it's one of their biggest customers.

Amazon, for example, runs much of the cloud computing for the Central Intelligence Agency. And just this week, Microsoft announced a deal to upgrade the Defense Department's computers with Windows 10. Apple, by contrast, has less need for government business. Its rivals "are a little bit uneasy doing things on the law enforcement side that might disrupt their ability to win contracts," Marc Rotenberg, president of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, told The New York Times.

In 2014, the government spent $447.6 billion on private contracting, including well over $60 billion on knowledge-based services, over $40 billion on research and development, and around $60 billion on technology services and equipment. All this makes the government a very big source of business for private enterprises across the economy.

It wasn't always so. Back in the day, the government tended to build its own buildings, clean its own buildings, and develop its own equipment in house. That started to change in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as the government came to rely more on the private sector. The original argument was that, thanks to market competition and the profit motive, private companies were better at creating efficiency, value, and well-designed institutions. So by doing less in house and relying more on private contractors, the government could both save money and deliver services better.

But even if you buy this argument, the modern world has brought an unexpected complication: The government also relies on cooperation from communication and technology companies in order to do a great deal of its surveillance and data gathering. And many Americans expect these companies to push back against government intrusions into privacy rights. But that's a lot harder for Silicon Valley to do when the government is also one of their biggest customers. Microsoft, for instance, helped the NSA bypass its own encryption. And the documents released by Edward Snowden showed other companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, and Yahoo all knuckled under at various points to the government's data gathering.

Today, the government slightly overpays people with high school education compared to the private sector — but it grossly underpays people with college and advanced degrees. If it was politically willing to spend the money, the government could attract a lot more quality resources and top tier talent to provide for its own logistical and technological needs. Such an approach might be "bigger" in terms of spending and operations, but it could allow also Silicon Valley and other companies to untangle themselves from the government, freeing them up to say "no" more often to its requests — and push back at the surveillance state.

Your biggest customers are the customers you really don't want to piss off. Perhaps it's better if the government isn't one of them.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

What to expect financially before getting a pet

What to expect financially before getting a petthe explainer Be responsible for both your furry friend and your wallet

-

Pentagon spokesperson forced out as DHS’s resigns

Pentagon spokesperson forced out as DHS’s resignsSpeed Read Senior military adviser Col. David Butler was fired by Pete Hegseth and Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin is resigning

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews