How can a computer glitch bring an airline to its knees?

It turns out that airline tech infrastructure is absurdly outdated

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After a crippling outage wreaked havoc on its computer system earlier this week, Delta canceled more than 1,000 flights and delayed some 2,800 more, frustrating passengers and no doubt putting a damper on many a holiday.

What happened? Here's how Delta Chief Operations Officer Gil West explained it:

"Monday morning a critical power control module at our Technology Command Center malfunctioned, causing a surge to the transformer and a loss of power," West said. "When this happened, critical systems and network equipment didn't switch over to backups. Other systems did. And now we're seeing instability in these systems."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So, basically, there was a power cut, and it screwed everything up. But as Delta continues to do damage control, the question remains: How is it that something as seemingly elementary as a power outage can bring the nation's second-largest airline to a screeching halt? Aren't there back-up systems in place? Stopgaps? Reserve power?

Yes, yes, and yes.

Gil Hecht, CEO of computer risk management and disaster recovery company Continuity Software, says Delta, like most major airlines, likely had one or more back-up systems in place to take over in an emergency like this. Often a company has an extra system housed in its main data center identical to the main system, plus another one in a separate data center in case both local systems are taken out in a major event, like a fire. Some companies even have a third redundant system that is cloud-based or housed in a separate location.

"Some of these disruptions should not have occurred," Hecht says. "Delta IT did something wrong that caused its redundancy structure to not function as needed. The problem was not the power failure itself; 99.9999 percent of power failures never cause service disruptions."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So, it shouldn't have happened. And, like so many of us have been before, Delta was at the mercy of its IT workers to get the problem fixed. But this definitely is not the first time a tech hiccup brought a major airline to its knees, and it certainly won't be the last. Just last month, more than 2,300 Southwest Airlines flights were canceled due to a "computer glitch." Why does this keep happening?

At the heart of this recurring problem lies a lot of outdated infrastructure. As the Wall Street Journal reports, many airlines rely on tech from the 1990s, which isn't particularly reassuring for travelers. Each year, airlines invest a sizable amount of money in updating this infrastructure — in 2016 alone, Delta has invested $150 million in upgrades and new systems — but these upgrades happen in a relatively patchwork fashion.

And making it even worse, Hecht says most airlines use manual testing to verify their data protection, meaning a human being actually has to take time out of their day to test the system on a regular basis. Other industries, like banking and finance, rely on automatic systems to lower the risk of a full blackout. Automated systems can be pricey, and while Delta's outage is probably costing the company a hefty sum (Southwest's outage last month was expected to cost the airline up to $10 million), an hour-long outage in the banking sector would create far more mayhem and profit-loss, so finance companies are more likely to pay up for automated systems.

This recent outage has inspired some soul-searching within Delta.

"It's not clear the priorities in our investment have been in the right place," Delta CEO Ed Bastian said. "It has caused us to ask a lot of questions which candidly we don't have a lot of answers for."

It took Delta several days to get everything back on track, partially because airlines are limited by the main service they provide: travel. As West put it, "When Delta doesn't fly aircraft, not only do customers not get to their destination, but flight crews don't get to where they are scheduled to be. When this happens, unfortunately, further delays and cancellations result. And flight crews can only be on duty for a limited time before rest periods are required by law."

In other words, one glitch, no matter how small, can be the first in a very long line of precariously-balanced dominoes. When one falls, it can take hundreds of flights down with it.

Industry analyst Henry Harteveldt said that for Delta, the most important thing will be figuring out why the multiple backup systems failed. This is even more paramount for the company than discovering why the system malfunctioned in the first place.

"It's not unlike an airplane accident where you want to go in and understand what caused the accident and how you can prevent the accident from occurring again," says Harteveldt. "These systems are very massive and complex in nature, and I think the employees feel frustrated that an airline like Delta that clearly invests a great deal in its aircraft, in its training, and in its technology, could have been brought to its knees by a system failure."

The next time you buy a flight, we suggest you invest in travel insurance, and pack an extra set of clothes, just in case.

Kari Paul is a Brooklyn-based writer covering technology, politics, and culture. Her work has appeared at VICE magazine, New York magazine, Elle, Cosmopolitan, and Quartz. You can follow her for more at @kari_paul.

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

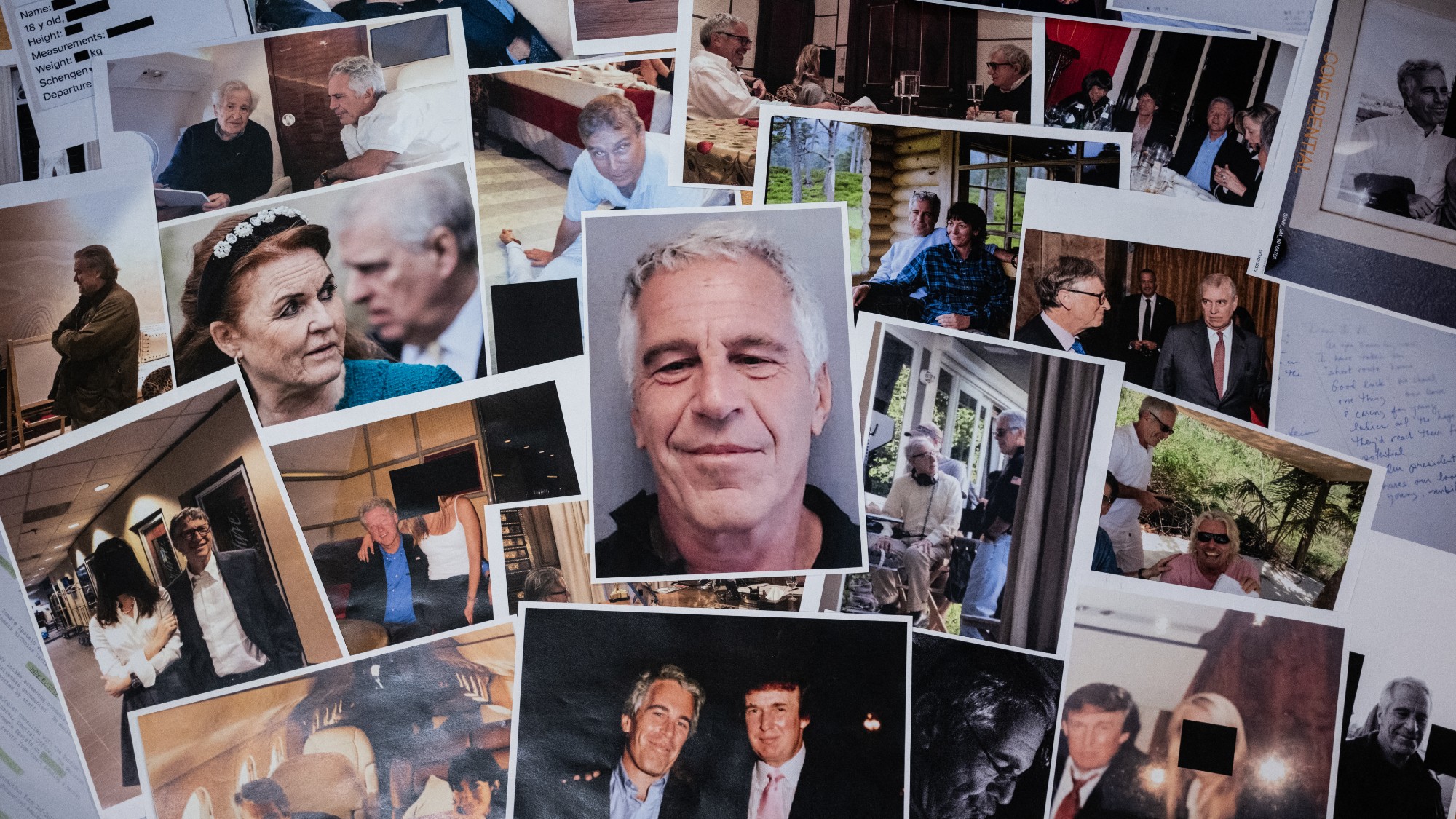

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral

-

Jeff Bezos: cutting the legs off The Washington Post

Jeff Bezos: cutting the legs off The Washington PostIn the Spotlight A stalwart of American journalism is a shadow of itself after swingeing cuts by its billionaire owner