Elvis, himselvis

Searching for the king in Graceland

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are some things — football, particle physics, heavy metal, and constitutional law among them — that I love, but don't love nearly as much as I love the way people love them. Give me a choice between watching the Super Bowl and watching people talk about the Super Bowl for two hours, and I'll always pick the latter: Listen to someone explain their passion, and eventually, they'll show you their soul. But at the very top of this list of loves, there can only be one man and one myth: Elvis Presley.

I love Elvis' music, his jumpsuits, his voice. I love his movies, from Love Me Tender (young Elvis playing rock n' roll in the aftermath of the Civil War; don't overthink it) to Change of Habit (grown Elvis romancing a nun; again, don't overthink it). I love the sexuality of young Elvis, which was so raw it achieved a kind of purity. I love the 1968 comeback special, which was once the only CD in my car for an entire year; I love "Hound Dog," which still thrills and baffles me as much as it did when I first heard it as a child. I love everything about Elvis, but I love his fans even more. I once went to an Elvis tribute artist competition (don't call them impersonators) in a casino on the Oregon coast, and felt the tremor of prayerful intensity that dominated the room when one of the good ones, one of the really good ones, took the stage. He performed "Baby Let's Play House," and for about three minutes, Elvis was alive.

The depth of desire needed to generate such magical thinking — such sheer magic, since I believed it, too — was enthralling, addictive. So I went to Graceland, Elvis' legendary home in Memphis, Tennessee. I had seen the fans and the imitators. Now, it was time to walk among the pilgrims.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When I arrived in Memphis this summer, Graceland was my first destination. Even if I hadn't had Elvis' home in mind, I would have been directed there soon enough. As you draw nearer to Memphis, the billboards beside the Interstate are soon dominated by his androgynously angelic face. "ELVIS LIVES," they proclaim, and you have to wonder whether Memphis itself has arrested all future development in the hope that sitting shiva for the king will make him come back someday. (After all, he was once a Shabbos goy.) Drive down a thoroughfare in Memphis and, aside from the cars, you can go for miles and see nothing to make you suspect that it is no longer 1977.

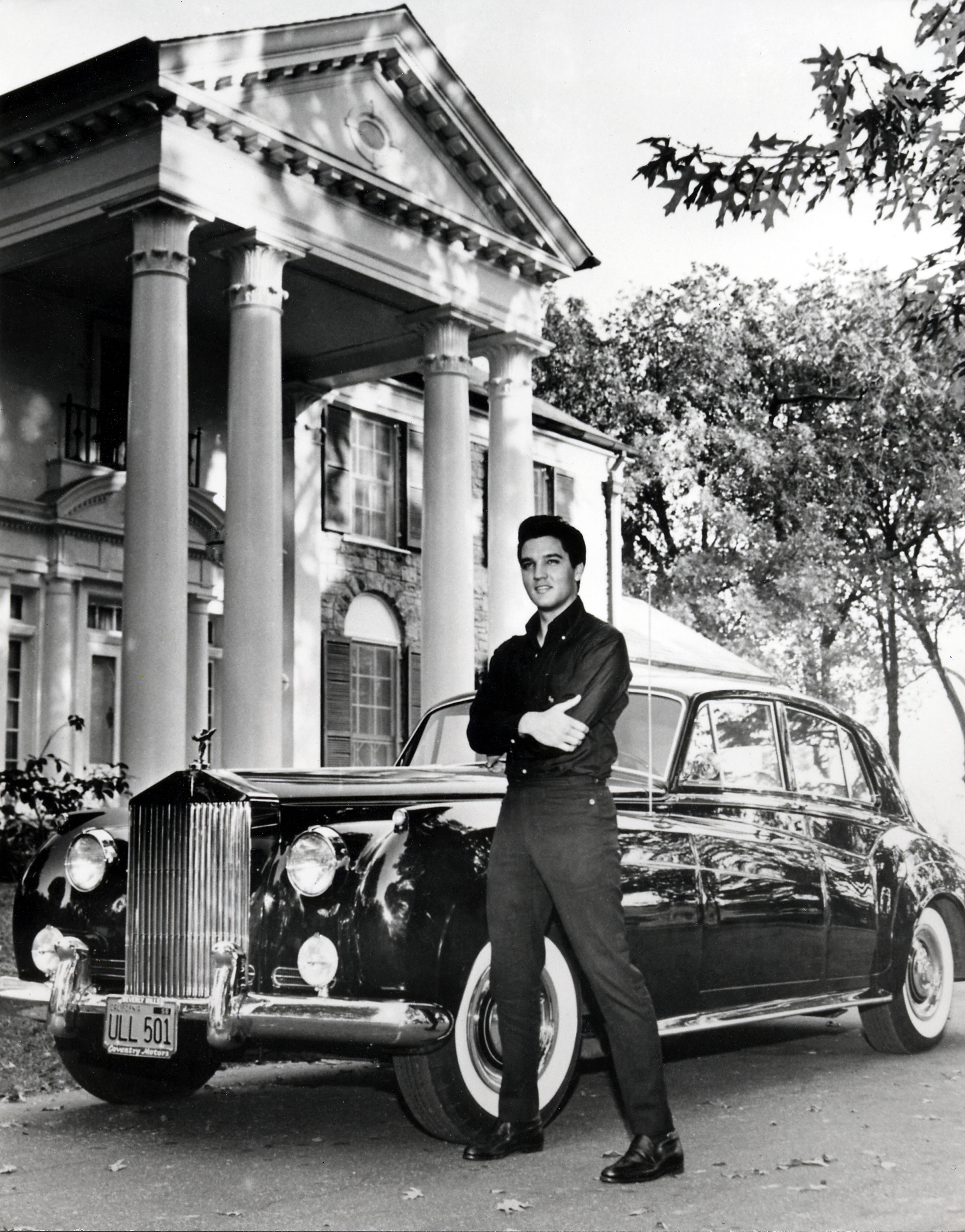

Memphis is a city of cracked asphalt, historic houses, and gaudy neon, and it is also, still, the city of Elvis Presley, who was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, but called Memphis his home long after his stardom achieved the kind of velocity that would have pushed another man, almost inevitably, to New York or Los Angeles. When he returned home from the Army in 1960, Elvis told reporters, "You'll never know how happy I am to be here. Someone asked me this morning what did I miss about Memphis, and I said, 'Everything.'"

Graceland is half theme park and half museum, and this moment is played over and over again on a TV screen in the former office of Elvis' father, Vernon Presley, which is curated to look exactly as it did in the days before Elvis left the building. During the same press conference, another reporter asks, "Did you leave any hearts, shall we say, in Germany?"

Elvis laughs and looks away, shyly, evasively, his face for a moment softening in bashful pleasure. "Not any special one, no," he says, looking back at the cameras. For the Elvis pilgrim, the real joy of this exhibit comes from the knowledge that "not any special one" is Priscilla, his future wife. At this point, the Graceland tour — which has already taken you through Elvis' living room and dining room, past the bedroom he kept for his parents and in whose closet Gladys Presley's dresses still hang, through the kitchen and down the stairs to the TV room where he watched three screens at once, past the jungle room with its green shag carpeting on the floor and ceiling, and out alongside the pasture where he rode his horses and the smokehouse where he shot his guns — will lead you into an exhibit detailing Elvis' life and career, including his wedding to Priscilla.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The space the exhibit takes up, with its glittering walls of gold records and "OY GEVALT ELVIS" buttons, is far more cavernous than Graceland itself. Compared even to the McMansions of today's suburb dwellers, Graceland is disarmingly small. It's not a castle built around a legend, but a medium-sized house bought and eccentrically decorated by a country boy who had suddenly come into some money. Graceland's upstairs, where Elvis retreated when he wanted to be alone, remains private: no tour goes there; no pilgrim visits.

It's not surprising, exactly, to see this kind of integrity on display in a tourist magnet that sells everything from postcards and key chains to Elvis-themed coffee and cross-stitch kits. But it is, at least in my experience as a lifelong lover of roadside attractions, a rarity. It seems that it must be difficult to profit so extensively from someone's likeness without eventually becoming somewhat jaded about the fact that they are, in fact, a real person. But this is not the case at Graceland. It is here because Elvis remains a myth, but its visitors come in search of the man.

Beyond the house itself, beyond the gold records, we walk past Elvis' movie costumes and his black leather jumpsuit from the 1968 special, past Priscilla's wedding gown and veil and TV screens playing footage of the couple on their wedding day (cutting the cake and sitting for a press conference, Elvis looking overwhelmed, Priscilla happy but composed, as if she has prepared herself for this kind of attention, at least for now). We walk past copies of checks displaying Elvis' contributions to local charities, past his Army uniform, and finally to the tuxedo he wore to accept the honor of being named one of 1970's 10 Outstanding Young Men by the United States Junior Chamber. It was the only award he ever accepted in person.

The honor was bestowed upon not musicians but humanitarians, and in Elvis' brief, uncommonly soft-spoken acceptance speech, it is possible to hear a man still working to understand how a few songs gave him the keys to the world, and what makes those songs — and maybe even their singer — worthy of such power:

When I was a child, ladies and gentlemen, I was a dreamer. I read comic books, and I was the hero of the comic book. I saw movies, and I was the hero in the movie. So every dream I ever dreamed has come true a hundred times. These gentlemen over here, these are the type of people who care, who are dedicated… I'd like to say that I learned very early in life that "Without a song, the day would never end; without a song, a man ain't got a friend; without a song, the road would never bend; without a song." So I keep singing a song. Goodnight. Thank you.

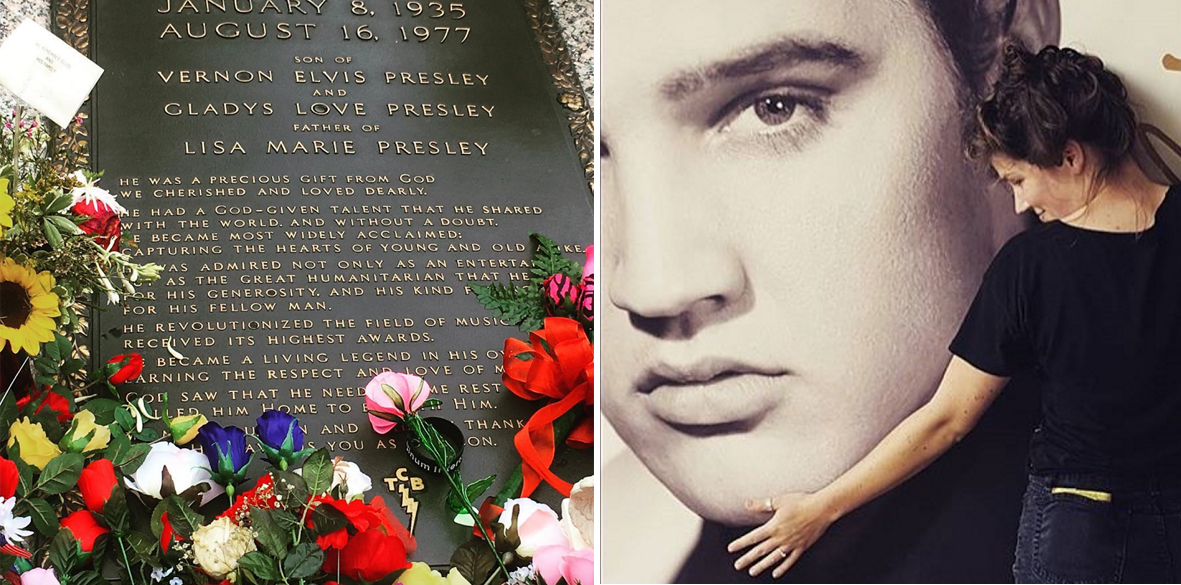

The museum progresses chronologically, ending in Elvis' death. Maybe there is a note of melancholy pervading the exhibit, or maybe I am feeling it all on my own. To me, it says: We loved you, and we killed you. That tuxedo — which is one of the few exhibits I didn't have in mind when I entered Graceland — is still on my mind when I emerge, blinking, into the sunlight, and walk with the other pilgrims to Elvis' grave. By this time, I know I am one of them.

It is Elvis week at Graceland, mere days before the 39th anniversary of Elvis' death. The following day, visitors will hold an all-night candlelit vigil. But for now, the bouquets and teddy bears and candles and heartfelt letters already cover Elvis' grave in bright drifts. The message is always the same: We love you, we love you, we love you. We will always love you. The greatest gift you ever gave was you.

Empty-handed, all I can do is look at these tributes, and try to read the story they tell. We are good, so good, I think, at loving. We can heap love on someone from afar; we can live in gratitude for years, for decades, if a sweet-voiced and loose-limbed country boy does nothing more than sing us a song. We are good at loving people who are distant enough to ask for nothing in return. We are good at the kind of love that makes a person into a myth, an idea. We have a harder time with the kind of love that means seeing another human being in all their complexity. We have a harder time with this kind of love because it is harder, because it is, maybe, the hardest thing on earth. But we want to learn it. We want to know it. So we come back to the site of some simple love gone wrong, a love whose power exceeded its use, and give not just tributes but apologies, tenderness, for years, for decades, for as long as we can, which turns out, sometimes, to be a very long time indeed.

I love Elvis, I think to myself as I leave Graceland, as much as I can love a human being I have never truly known. But, maybe more than anything else about him, I love him for the fact that both his presence and his absence created a space for people to come together and try to comprehend the capacity for destruction and redemption, the sheer power, of their love. I love the potential for intimacy and revelation such a space allows. I love that it has lingered long enough for me to find it. I love it even more than the key chain I bought.

Sarah Marshall's writings on gender, crime, and scandal have appeared in The Believer, The New Republic, Fusion, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2015, among other publications. She tweets @remember_Sarah.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions