How the geeks inherited the Earth

Geeks are winning at business and politics and culture. Is it too much to ask for a little respect?

In 2008, the United States elected its first Trekkie president.

Wired highlighted Barack Obama's self-identification on the campaign trail — "I grew up on Star Trek. I believe in the final frontier" — and proclaimed Obama "a big geek" and "also the first geek president." Obama seemed to embrace the label. He's guest-editing Wired's November issue.

Geeks: You've come a long way, baby.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It goes beyond politics, of course. We see the ascendance of geeks in tech, business, and pop culture, too. The wealthiest person in the United States, and usually the world, is proto-geek Bill Gates, the uncool computer baron from the 1980s. Right up there with him are Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, Amazon's Jeff Bezos, and Google's Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

Today's only reliable Hollywood blockbusters are based on comic books. Doctor Who is almost cool (even if bowties still aren't), and you can find sonic screwdrivers and other Tardis paraphernalia in gift shops and bookstores patronized by non-geeks. You could draw a pretty straight and solid line between nerd basement staple Dungeons & Dragons and Game of Thrones, the most talked-about show on TV for several years running. Celebrities un-self-consciously discuss their love of comic books on late-night TV and in magazine profiles. Jeff Goldblum is a legitimate movie star. Hackers and rogue IT guys are either public heroes or Public Enemy No. 1, depending on your point of view. Video games are now a $23.5 billion industry in the U.S., $99.6 billion worldwide.

The geeks have inherited the Earth.

Lord knows they didn't start out at the top. Dictionaries trace the word "geek" back to 19th century England, a variation on "geck," meaning fool, from Germanic dialect. A related word in Dutch, "gek," means mad or silly. In early 20th century America, "geek" meant carnie — or "a carnival 'wild man' whose act usually includes biting off the head of a live chicken or snake," according to Webster's New International Dictionary circa 1954. By the 1980s, geek had assumed its modern definition of a socially awkward person with unfashionable interests, notably computers, science fiction, and comic books.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Being called a geek was never a compliment. They were always the outsiders. In popular culture, geeks have long been comic relief or objects of derision or pity. Even when nerds took their revenge against the jocks, their aspirations were so modest: tolerance, a girlfriend, a quantum of respect.

For geeks, things began changing in the 1990s. There were little clues. On the quintessentially '90s TV show Friends, Rachel dated Ross the geeky paleontologist, not Joey the beefy actor. A respectable Shakespearean actor, Patrick Stewart, signed on for a Star Trek reboot, and The Next Generation was a mainstream hit by the time it ended its run in 1994. By 1999, the hunky Keanu Reeves was starring as a hacker messiah in The Matrix, and geeks were no longer comic relief on TV — in fact, they had their own show (which they shared with the freaks).

Probably the biggest factor in the rise of the geeks, however, was technology. In the 1980s, computers were no longer room-sized mainframes, but they were largely tools. In the '90s, utilitarian Microsoft Windows crushed Apple's Macintosh fiefdom, forcing Steve Jobs into retirement (and over to Pixar). But by the end of the decade, Apple and Jobs were back with the iMac, a colorful consumer machine geared toward the burgeoning internet. Thanks to the internet, geeks in Silicon Valley and Seattle and a few other tech capitals were suddenly millionaires. AOL bought Time Warner. The world was crazy — anything could happen.

What did happen, of course, was the dot-com bust. But the geeks were more necessary than ever. Every company needed an IT team — and if you wanted to rent your own, Best Buy had (and still has) its "Geek Squad." Napster got sued to (virtual) death, but it had convinced everybody to listen to music on their computers, and Apple jumped on that to churn out a series of consumer electronic revolutions that made tech not just useful to people but objects of desire. Tech wasn't just PowerPoint and Excel anymore, it was iPods and iPhones.

Moreover, the internet gave people with particular interests a place to follow them, and to build a community, and for technically inclined people who felt more comfortable in cyberspace than among flesh-and-blood people, the internet changed everything. Once online networking became easy, it turns out geeks had plenty of company. The people who helped connect people and aided their quest to find their niches — Facebook and Google, for example — are billionaires.

Money, prestige, and power aren't everything, of course. And not all geeks have any of those. But most of the geeks of the 1980s seem to be doing alright, and today's young geeks, still finding their place in the world, have destigmatizing role models in pop culture and brighter-than-average career prospects.

But have geeks really risen to the top, past the jocks and the cheerleaders, the punks and rebels, the drama club weirdos, the future farmers and business executives of America? Obama, remember, can sink a 3-pointer and trash-talk on the court as well as make the Vulcan hand sign (and he sometimes gets his geeklore wrong). Plenty of titans of business and finance were never geeks, and Congress is full of glad-handing alpha male and female types.

And do we even want geeks to take the reins of society and business and government? Geeks aren't necessarily benign. (Google "gamergate.") Sure, Google aspires to "do no evil," but the company knows more about you than most of your friends, probably, and it makes money off that knowledge. So does Facebook. Edward Snowden, whether you like what he did or not, rocked the boat, hard. Would the new boss be any better than the old boss, or just less socially graceful?

It turns out we are about to have an imperfect test of where we stand on the geek question.

First, a short note about semantics. Nerds and geeks are generally understood to be different social subgroups, though the difference is subtle and has diminished over the years. Nerds were generally smart and unpopular, while geeks were technically savvy, unpopular, and had particular uncouth interests. With geeks, there was always an undercurrent of obsessiveness — precursor to the modern phrase "geeking out." Think of it this way: Obama is a geek, but Hillary Clinton would be considered a nerd, whip-smart and always meticulously prepared, never the most popular kid in class. Donald Trump is neither. He's the bully, the self-obsessed rich preppie. In the John Hughes classic Pretty in Pink, he's James Spader's Steff McKee, the wealthy jerk out for revenge because he was turned down by the girl from the wrong side of the tracks.

Here's the thing: For most of recent history, the geekier candidate has lost the presidential election. Before the current Vulcan-in chief was elected, back-slapping political scion George W. Bush beat John Kerry and Al Gore (another Star Trek fan), "big dog" Bill Clinton beat septuagenarian Bob Dole and George H.W. Bush, Bush beat the even-nerdier Mike Dukakis, former movie star Ronald Reagan beat Walter Mondale and Jimmy Carter, and so on, back at least until Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower beat the bookish Adlai Stevenson, twice.

If America picks the female wonk over the tough guy, that's one more data point to consider.

Collectively, geeks probably don't care if they conquer the Earth. Presumably they just want to have an equal shot at success and happiness as the groups they coexisted with — happily or not — in middle and high school. If they are typically faring a little better, or a lot better, who's to complain?

But this much seem inarguable: The world of 2016 is much more accepting of differences, and much less tolerant of perceived bullying, than the world of 1986, or 1956, or anytime before that. If we take that to be self-evident today, good. Anything else would be highly illogical.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

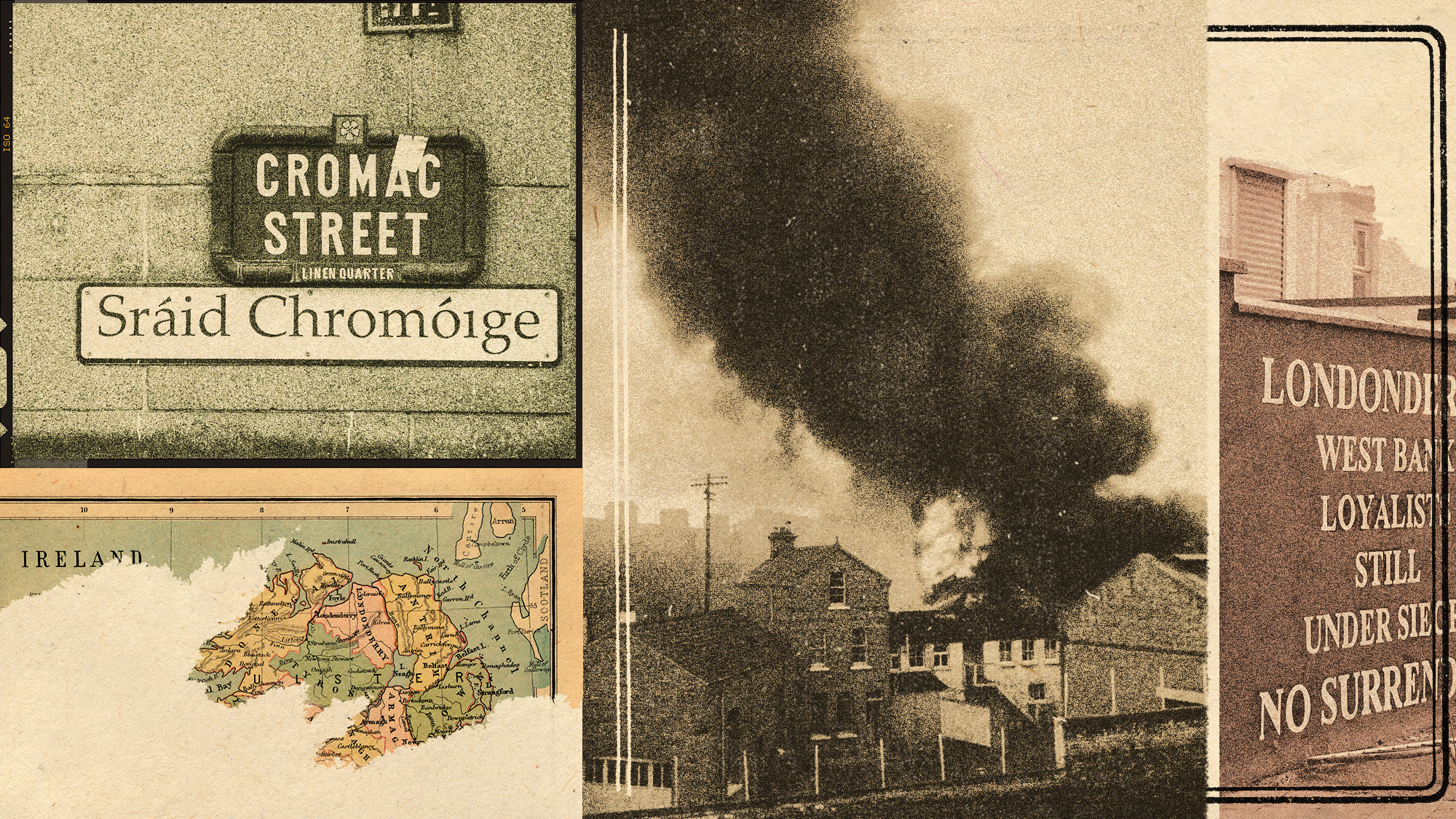

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels