How lead poisoning wreaks havoc on American education

This might be the most underreported issue in school reform

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It didn't come up much during the presidential primary, but the fight over education reform is one of the biggest rifts in the Democratic Party. Simplifying somewhat, on the one side are leftists and teachers' unions, who favor traditional public education, teacher tenure, and generously funded schools. On the other are school reformers and a slew of billionaires, who favor stringent performance metrics for teachers and students, making it easier to hire and fire teachers, and privately-run charter schools.

Hence when John Oliver did a long segment on HBO about hideous mismanagement at some charter schools, the Center for Education Reform put out a $100,000 bounty for the best video response from an individual charter school.

It's an interesting debate — but the education reformers are missing some low-hanging fruit. Most research I've seen suggests that, on net, charters aren't that different from public schools. Some do better, a larger proportion do worse, and a larger proportion still do about the same. However, there is one simple and easy reform that would help American children, especially minority ones: Put a stop to lead poisoning. It turns out being poisoned with heavy metals is none too great for children's education — and a new study demonstrates that even very small amounts of lead poisoning can damage children's learning.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lead was thought to be a solved problem for quite some time, since leaded gasoline and paint were both phased out in the 1990s. It has come back in view due to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan (which isn't remotely resolved, by the way) — but still in a limited way. That ongoing disaster rather makes it appear as though lead poisoning is mainly an issue for crumbling Rust Belt cities with severe economic problems.

This is not the case. As Julia Lurie points out, data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that lead contamination is a serious issue all over the country. Only about half of states even report lead data from children's blood samples, but those that do show many counties with serious lead contamination — naturally those with high poverty and/or high minority populations.

And as a new NBER working paper demonstrates, even very small amounts of lead appear to have negative effects on children's education. The study looked at data from Rhode Island, where very thorough lead testing data allowed them to control for many confounding factors. The result:

[W]e show that reductions of lead from even historically low levels have significant positive effects on children's reading test scores in third grade... Estimates suggest that a one [part per billion] decrease in average blood lead levels reduces the probability of being substantially below proficient in reading by 3.1 percentage points. [NBER]

This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed, so such an effect is not an ironclad certainty. However, prior knowledge and common sense militate powerfully towards accepting its thesis. We know for a fact that lead causes brain damage and sundry social malfunctions — indeed, there is a strong argument it caused the mid-century crime wave. If there's even a moderate chance of protecting children's brains with aggressive abatement, we should seize it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And on the other hand, it's not like there's a risk of children getting too little lead.

Ideally the federal government should be the one to handle this problem. It has the deepest pockets, and the greatest reach throughout the country. Indeed, Hillary Clinton has proposed a pretty good lead abatement plan, attacking pipes, paint, and contaminated soil. But given probable Republican control of Congress, there's little chance this will pass in the near term.

However, the pockets of the school reform crowd are still quite deep. If the Gates Foundation decided to dedicate a significant portion of its $39.6 billion to systematic lead abatement, it could make a significant difference. It's a way to prevent child brain damage, improve school achievement — and all without needing to get in a brutal political fight with teachers. For a sensitive-minded billionaire, what's not to like?

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Russia: 19-year-old gunman killed at least 7 students, teacher at middle school

Russia: 19-year-old gunman killed at least 7 students, teacher at middle schoolSpeed Read

-

2 American students found guilty of killing Italian policeman

2 American students found guilty of killing Italian policemanSpeed Read

-

At least 18 killed, dozens wounded in suicide bombing outside Kabul education center

At least 18 killed, dozens wounded in suicide bombing outside Kabul education centerSpeed Read

-

Oregon becomes 11th state to require Holocaust education in public schools

Oregon becomes 11th state to require Holocaust education in public schoolsSpeed Read

-

Students at Ole Miss vote to remove Confederate statue from center of campus

Students at Ole Miss vote to remove Confederate statue from center of campusSpeed Read

-

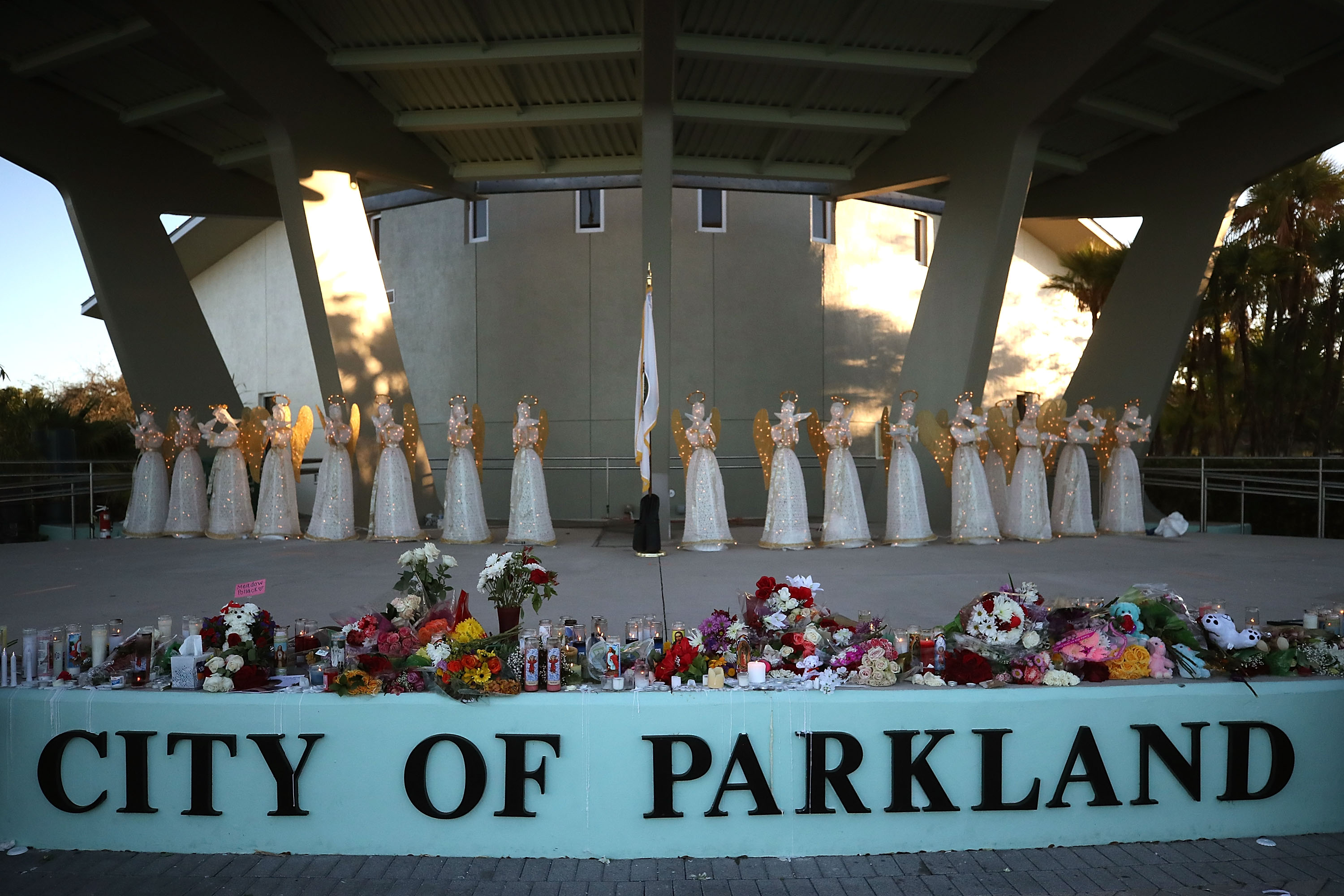

Judge rules police did not have a duty to protect students in Parkland shooting

Judge rules police did not have a duty to protect students in Parkland shootingSpeed Read

-

At least 79 students abducted by separatists in Cameroon

At least 79 students abducted by separatists in CameroonSpeed Read

-

Nikki Haley says China's 're-education camps' are 'straight out of George Orwell'

Nikki Haley says China's 're-education camps' are 'straight out of George Orwell'feature