America is on the verge of a tech panic. And Silicon Valley isn't helping.

If those fabulously wealthy folks are gloomy about tomorrow, what hope do the rest of us mere mortals have?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Microsoft cofounder BIll Gates muses about taxing robots to slow down technological progress. Tesla CEO Elon Musk wants to regulate artificial intelligence, calling it "a fundamental risk to the existence of human civilization." And Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg thinks mass tech-fueled unemployment might make a universal basic income necessary.

What's this all about? Isn't Silicon Valley supposed to be a font of perpetual, over-the-top optimism? I thought we could solve just about any problem with enough applied data or a really clever algorithm. If those fabulously wealthy folks are gloomy about tomorrow, what hope do the rest of us mere mortals have?

After all, it's been a terrible decade for the U.S. economy. A horrific financial crisis was followed by a historically weak recovery. Every silver lining seems surrounded by a big dark cloud. America is creating lots of jobs, for instance, but wage growth remains so-so. And we're probably still not back to full employment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But one part of the American Growth Machine that does seem to be fully in gear is the technology sector. The world's four most valuable public companies are American tech giants: Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Amazon. The U.S is also home to some 100 startups worth at least $1 billion each — more than twice as many as Asia and six times as many as Europe. What's more, tech innovation may be stronger than economic data suggests. Recent research finds tech equipment prices are probably falling faster than official measures show. That implies innovation in the digital economy is even faster than we think.

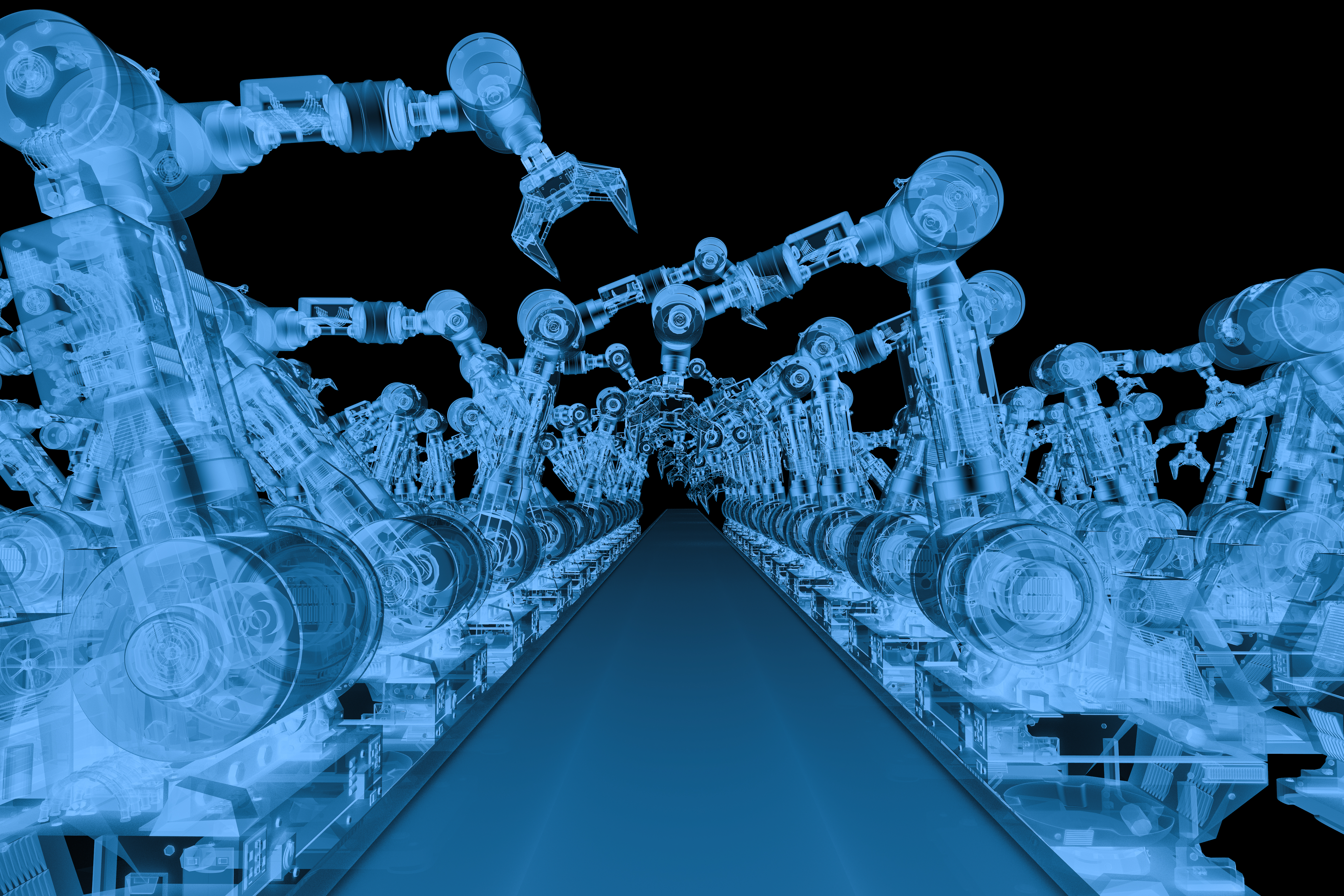

And things could get even better. All that innovation has yet to really show up in the productivity numbers that feed into GDP and income growth. But sometimes growth lags behind innovation as businesses work out how to best use new technologies. For instance: It took factories decades to efficiently reorganize themselves around the installation of electric motors. In the 1980s, economists wondered why the computer revolution was having so little observable economic impact. But then came the 1990s internet boom. And some experts think a host of new tech and applications — AI, robotics, e-learnings, big-data analytics — may be ready to transform the physical economy, generating faster growth and higher incomes.

Unless, of course, we screw things up with an anti-tech backlash. As I wrote for the The Week last year, it's not a huge leap from populist politicians blaming trade for all our troubles to blaming robots. There will always be opportunists who play on people's fears. And those concerns might only increase as tech further disrupts the economy and workers' lives. We might be entering an extended time of "technopanic," according to analyst Adam Thierer. Imagine a bell-shaped curve illustrating a "cycle of panic." Starting at "trusted beginnings," Thierer explains, the curve ascends left-to-right to "rising panic" and peaks at "the height of hysteria" before descending to "deflating fears" and finally "moving on."

Unfortunately, we are still probably on the fearful left side of the technopanic curve with the worst yet to come. An analysis by Baylor University researcher Paul McClure found 37 percent of Americans fit the definition of a "technophobe," and are more worried about losing their job to a robot than a romantic breakup or public speaking.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But here's the thing: We need more innovation spread throughout more of the economy to boost living standards over the long term. So maybe the tech community should focus harder on thinking of ways — innovative education and retraining applications seem critical — to make sure the economy, as Dartmouth University political scientist Russell Muirhead writes in a recent essay, "produces wealth and work." Americans need to hear a plausible story about how that happens, and Silicon Valley has a role to play in helping tell it. It's certainly in the self interest of Big Tech to do so given how activists are using fears of tech-driven joblessness to argue for expansive regulation or antitrust actions against them. At least in the near term, that's a far more likely scenario than AI enslaving humanity.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.