The dress that ignited the slave trade

When a portrait of Marie Antoinette wearing a simple muslin gown appeared in 1783, it caused a scandal. It also ignited a feverish demand for cotton.

Marie Antoinette is infamous for her lavish, over-the-top fashions. It is the first thing most people associate with the doomed queen — skirts as wide as they are tall paired with towering hairstyles, all draped in jewels and pearls. She was a fashion icon; if Marie wore a style, the rest of the court — and the Western world — followed suit.

She had the power to make or break an entire industry just by deeming something fashionable, and though it wasn't her intention, that is exactly what she did. Yet despite all of Marie's extravagant fashions, it was her most unassuming look that changed the world forever.

In 1783, portrait artist Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun painted Marie in a simple cotton gown known as a robe de gaulle. The thin, white fabric is airy and loose, cinched at the waist with a sheer, golden sash. Full sleeves and a softly ruffled neckline add volume to the otherwise unstructured shape. She doesn't wear any jewels or embellishments, just a wide-brimmed straw hat tied with a ribbon band, topped with a few relatively modest plumes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The painting has a graceful and arcadian feel to it, at least to the modern eye. The scene is refreshingly natural when compared with the ornateness of the typical rococo-era portrait. The gown gives off "an aesthetic of rustic simplicity," writes Katy Werlin in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion From Head to Toe.

Despite its humble appearance, though, Marie's portrait in the plain cotton dress had an impact that reverberated throughout the world in ways no one could have foreseen. It flipped the textile industry on its head, lighting the fuse laid out by a fast-changing world of exploration, the Enlightenment, and rebellion. It caused cotton, and the institution of slavery it stood on, to explode.

When Austrian-born Marie Antoinette was sent to France at just 15 years old to marry the dauphin, she entered a world of extraordinary opulence. Versailles was home to the most lavish halls and grounds imaginable, and the people who occupied it dressed to match. Marie dressed as she was expected to, in the finest French silks with jewels fit for a future queen. She was not the first to wear the over-the-top styles; she was simply in a position to take them to levels with which even the most privileged members of the aristocracy could not compete.

When Marie's husband, Louis XVI, ascended to the throne in 1774, he gifted Marie with the Petit Trianon, an idyllic château on the grounds of Versailles first occupied by Louis XV's mistress, Madame du Barry. The Petit Trianon was Marie's personal escape. She was given complete control of the estate; even the king could not enter if she did not invite him. Marie and her ladies would go there to step away from their lavish lifestyles and enjoy a simpler existence, undisturbed by the scrutiny and expectations of the court. Naturally, this extended to their clothing. They left their stiff silks behind in favor of light muslins and brightly patterned cotton chintz and indiennes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At this point in time, the vast majority of cotton came from India (hence "indiennes"), and thanks to the East India Company, it was spread across Europe. Native Americans had grown cotton in the southern United States for centuries, and as the colonists took over the New World, they, too, grew small amounts of cotton, but very little was exported.

Much of the American agricultural industry in its infancy was supported by indentured servants. While slavery certainly existed in the United States at the time of Marie Antoinette, its future was uncertain. Shortly after the American Revolution, the Northern states outlawed slavery one by one, and for a brief time, it looked as though the Southern states might do the same. That all changed as cotton began to rise.

It is not surprising that Marie would choose to be painted in the fashion she wore in her private oasis. She was by no means the first to be depicted wearing the provincial cotton dress that typified life at the Petit Trianon. Within the French court alone, Vigée Le Brun painted a few aristocratic ladies in the gauzy gowns, including Madame du Barry in 1781 and the Duchess de Polignac, one of Marie's closest friends, in 1782 and 1783. These women were both already controversial figures to the people of France, and while their choice of cotton gowns stirred up some level of dissent, it was nothing compared with the uproar that exploded when Marie's cotton-gown portrait was put on exhibition at the Salon of the Académie Royale.

The backlash was immediate. Salon visitors demanded the portrait be removed from public view, but the damage was already done. As Mary D. Sheriff states in The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art, "Vigée-Lebrun unwittingly showed her [Antoinette] as an immodest woman, providing enemies with yet more evidence against the queen."

There were many who saw the garment as alarmingly scandalous. It closely resembled a chemise — the simple dress that served as a base garment for women at the time. In other words, the queen appeared to be posing in her underwear. This accusation gave the cotton gown the name by which it is now most commonly known: the "chemise à la reine," or the "chemise of the queen."

Beyond the shocking nature of the gown's design, the fabric itself was a source of major uproar. Many of her fellow aristocrats saw the queen in such an inexpensive textile as a breakdown of the barriers between the classes. More importantly, though, cotton was seen by the French as a very English fabric, since India was a British colony. Cotton chintz had risen in popularity throughout the century in Britain and was a fashionable choice on that side of the English Channel by the 1780s. Therefore, it was perceived as incredibly unpatriotic for the French queen to so openly wear cotton. Her loyalties were already under question due to her Austrian heritage, and this dress only confirmed her lack of French allegiance. The queen's many critics were concerned that this choice would destroy the French silk industry.

Despite the controversy, the 18th-century fashionistas who were unafraid to take risks expanded the popularity of the chemise à la reine. In The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1780–1820, Aileen Ribeiro recounts how Marie sent chemise gowns to a few of her friends, including the famous British style icon Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire.

Soon, what was once seen as scandalous was now seen as stylish, and the chemise à la reine became a popular choice of dress for women across Europe. Paired with the rising affinity for Greek and Roman culture brought on by the Enlightenment, the plain white dress quickly took over the fashion world.

As everyone knows, Marie Antoinette was executed in 1793 for reasons that went far beyond her contentious dress. But although the queen was gone, the impact of her sartorial choice was just starting to make its mark.

The people of France had been right to be concerned about the popularization of cotton and other muslins. Throughout the next two decades, the French silk industry suffered greatly. While the French Revolution had a massive impact on the economy across the board, the demand for silk both in France and abroad came crashing down as the simple white muslin dress became the leading style.

However, as the Revolution progressed, the general French perception of the patriotism associated with cotton completely reversed. As Caroline Weber writes in her book Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution, "Once condemned as ruinous to the domestic silk industry, muslin could now be worn as a sign of patriotic ardor, along with even cheaper stuffs like cotton and wool, since the nobility's costumes at the Estates General had marked 'sumptuous silks and velvets as enemies of the Revolution.'"

By the end of the century, cotton and muslin had nearly completely replaced silk as the fashionable fabrics of choice. Yet the fall of silk and rise of cotton had implications that reached much farther than the borders of France. The Indian cotton industry could no longer keep up with demand, so Europeans were forced to look elsewhere for their supply. Up until the end of the 18th century, tobacco and rice and other food products dominated the American agricultural industry. That all changed when the demand for cotton suddenly skyrocketed.

While the simple cotton dress was rising in popularity, the Industrial Revolution was making major strides to aid in textile production. When Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1794, suddenly there was the technical ability to process cotton at a rate to keep up with demand. All that was necessary was the workforce to pick large volumes of cotton so it could be processed by the gin.

Of course, plantation owners looked to the cheapest possible option. The boom in the agricultural industry caused a boom in slavery to support it. According to American Slavery: 1619–1877 by Peter Kolchin, "annual cotton production rose from about 3,000 bales in 1790 to 178,000 in 1810, then surged more than 20-fold during the next half century." The slave population increased in turn, from about 654,000 slaves in the South in 1790 to more than 1.1 million in 1810, a number that continued to grow in the following decades.

Marie Antoinette and her fellow fashion trendsetters made cotton desirable. Technology and slave labor made it affordable. It was the perfect storm. The affordability increased the desirability, resulting in an even higher demand, which in turn increased the mass production so that the price dropped even further.

The cycle caused "King Cotton" and the institution of slavery that it stood upon to rule the South. Of course, we all know what happened from there. A simple dress launched an elaborate butterfly effect with far-reaching consequences that the young French queen never could have predicted when she took a step outside her lavish royal wardrobe.

Originally published at Racked. Reprinted with permission.

-

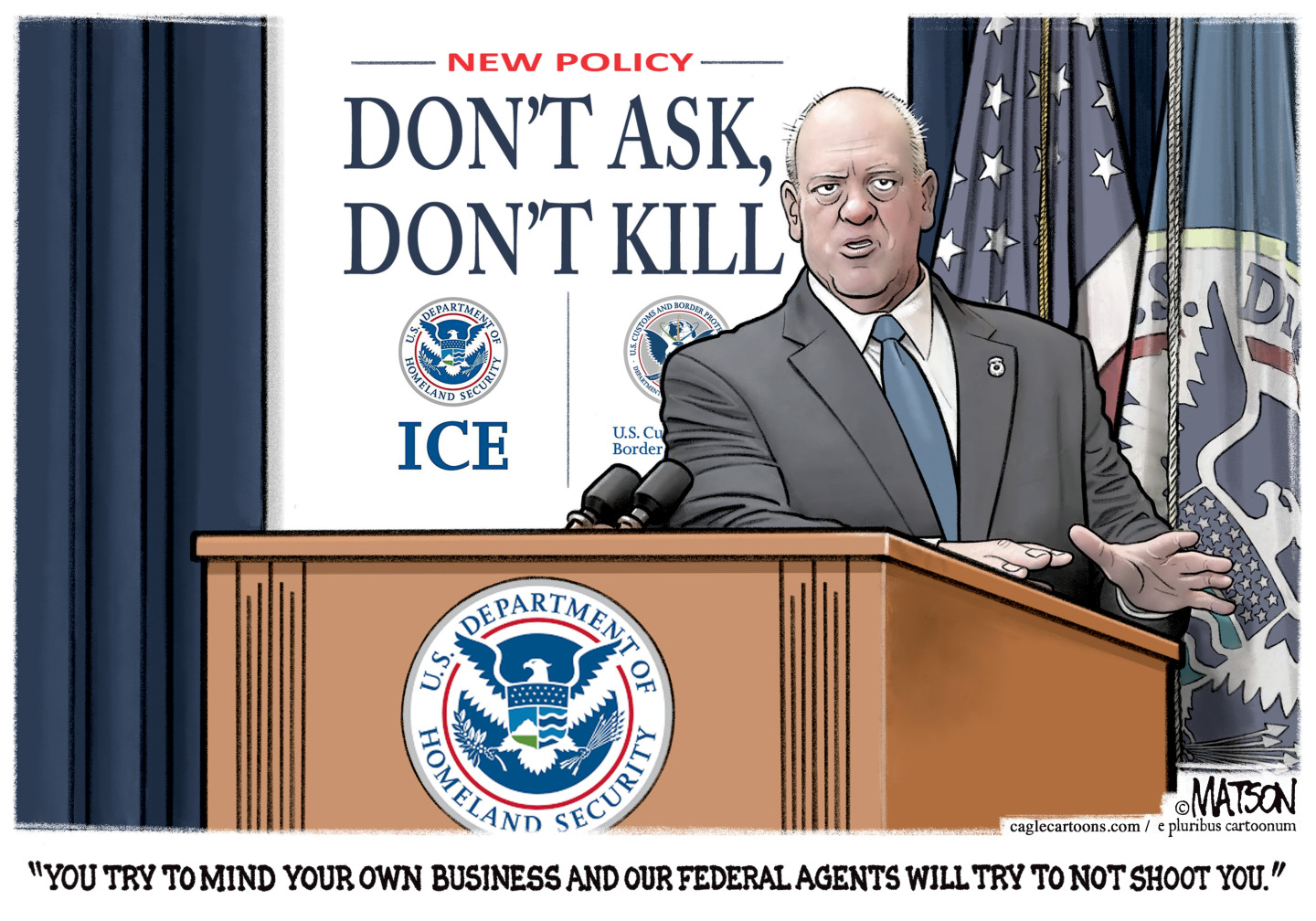

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’