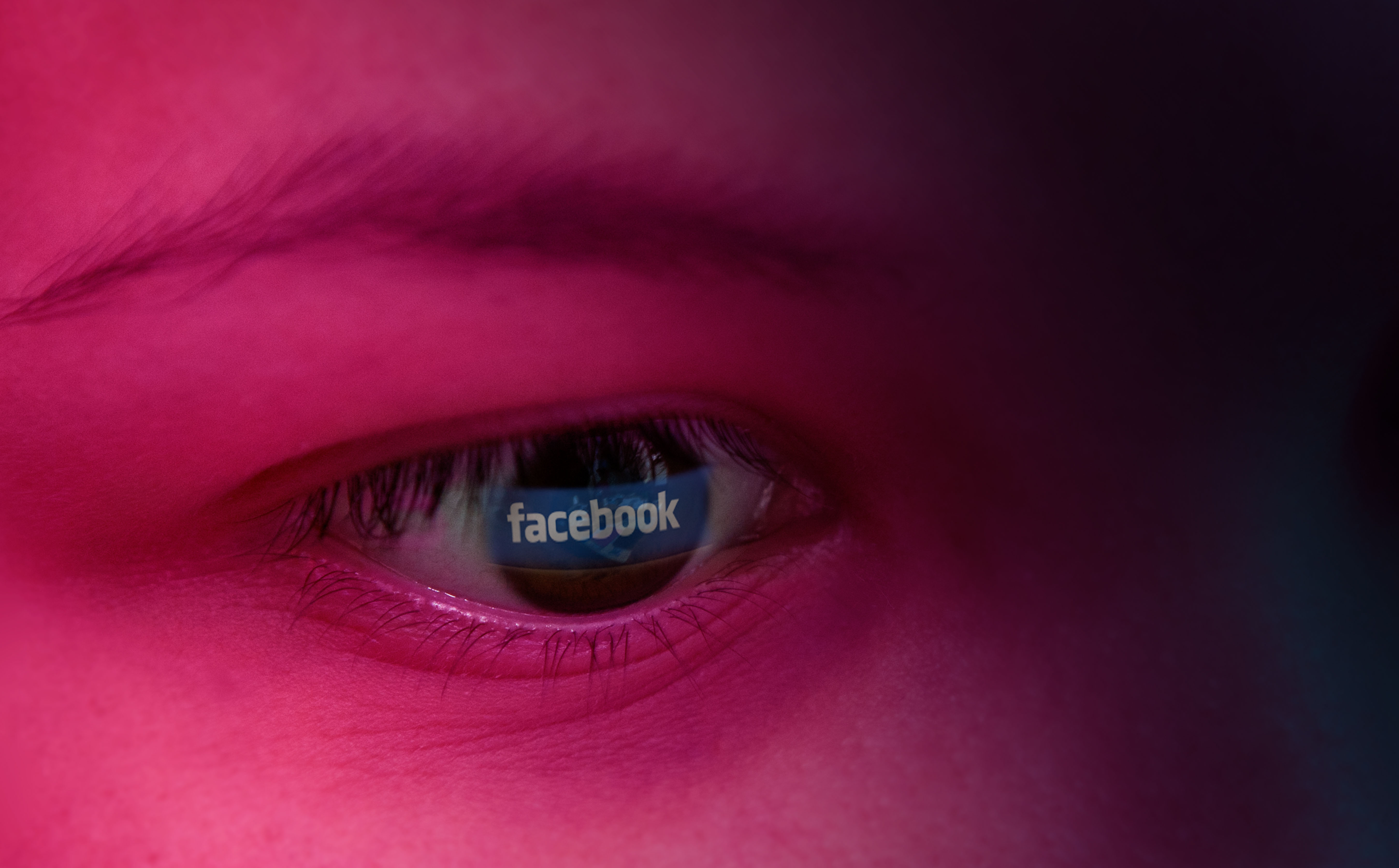

Is the anti-Facebook hysteria really about data privacy?

Americans sure don't act like they're very concerned about safeguarding it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Things could be even worse for Facebook. At least President Trump doesn't hate CEO Mark Zuckerberg with the white-hot intensity of a thousand suns, as he apparently does Amazon boss Jeff Bezos. That said, the Cambridge Analytica data-privacy scandal has already cost Facebook $50 billion in market value, with Zuckerberg's personal wealth down $15 billion. Whether or not Facebook stock rebounds depends in large part on whether users really do #DeleteFacebook.

Facebook's superpower is its nearly two billion users. If they and their valuable data stick around, so will Facebook's advertisers and investors.

Making sure that happy ending happens is why Facebook is quickly rolling out new features to give users better and clearer control over how their data is used. Even the social media giant's more devoted followers would have to concede the current interface is a hot mess. Too bad it took the biggest crisis in the company's history to nudge an update.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We'll see if these changes and some soothing words by Zuckerberg before Congress will reassure users. Facebook's next couple of quarterly reports will be scrutinized as perhaps none before. If they show no hemorrhaging of users, Team Zuck can probably breathe a massive sigh of relief.

Which they probably will. Despite all the alarm about Cambridge Analytica and Facebook's past lax privacy practices, it remains an open question how much people really care about data privacy, other than keeping their financial info secure. Much of the hysteria may actually be fueled by the perception that the data leak aided Trump's election victory, building on the outrage over Russian meddling on Facebook.

After all, Democrats who are now fretting that Cambridge Analytica's dodgy "pyschographic" profiling helped swing the election to Trump were unconcerned when the 2012 Obama campaign used similar techniques, though without violating Facebook's rules that were in place at the time. Likewise, Republicans are far less concerned about Russian activities on Facebook than their perception that Facebook, like other Big Tech companies, has picked the wrong side in America's culture war.

Indeed, there has always been a disconnect between public expressions of concern about privacy and how people actually behave in front of a monitor or look at their smartphone. For instance: One new Facebook feature makes it easier for users to employ two-factor authentication on their account. But how many people will actual take this simple security step to help stop hackers? If Google's experience is any indication, not many. Fewer than 10 percent of Google users have enabled two-factor authentication. Just too much of a bother for most of us. Much easier, I guess, to answer a survey question that expresses deep concern about privacy. Lots of polls show this, like a 2015 Pew Research survey that found 74 percent of Americans were "very concerned" about who could get info on them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But we sure don't act like we're very concerned, at least when it comes to social media. As a 2017 Harvard Business Review article on online privacy highlights, there is research suggesting "nearly 40 percent of Facebook content is shared according to default settings, and that privacy settings match users' expectations only 37 percent of the time." Yet people continue to login. Why? One reason, the HBR authors offer, could be the common psychological quirk of "third-person risk." It's the "Hey, it can't happen to me" syndrome.

A more likely explanation, however, is that people find a lot of value in using free internet services — whether Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram, or Twitter, Snapchat, or Google — and exchanging data for those highly-valued services is a worthwhile exchange. And it is. The ad-supported business model, driven by user data, is the beating heart of the internet economy and everything we love about it, from search to maps to cat videos.

So perhaps the concern about privacy is really just a stand-in for a broader unease with the disruption inherent in technological progress. Will the robots take my job? Will only driverless cars be allowed on the freeway? We are embarking upon a new economic revolution whose exact path forward and ultimate destination is uncertain. And, of course, there are some tech industry critics who are using today's privacy concerns as a convenient cudgel to attack the companies as they argue for heavy regulation and/or dismantling.

When Zuckerberg testifies before Congress, he needs to do more than show how he's fixing Facebook. He needs to begin making the anti-"techlash" case to policymakers that the data bargain is one still worth making, and that Big Tech is still a force for good in the U.S. economy and American society.

Time is of the essence. You never know when Trump will start tweeting about "Fakebook."

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day