Why I flew 2,000 miles to say goodbye to a freeway overpass

On our nostalgia for eyesores

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last Thursday, I left my apartment in New York City and flew 2,400 miles to say goodbye to one of America's worst pieces of infrastructure.

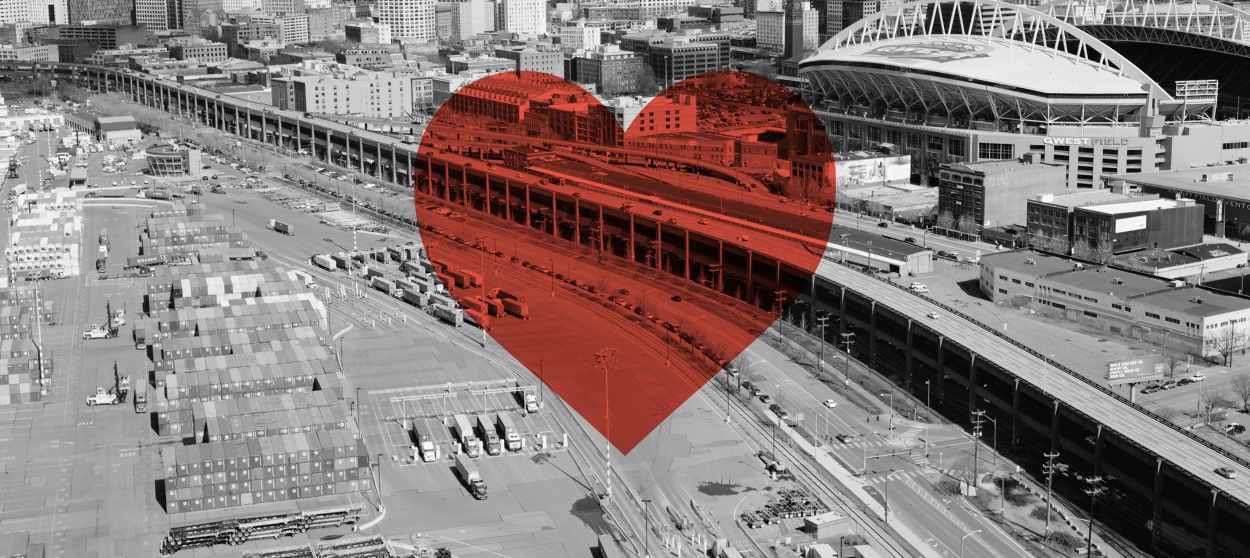

Seattle residents have despised the Alaskan Way Viaduct since even before it was even completed in the 1950s. Built to bypass downtown congestion, the double-decker freeway was made from some 122,000 tons of reinforced concrete and stretched for 60 years like a gash through the heart of Seattle's scenic waterfront, casting a damp and gloomy shadow over anyone making their way to the aquarium or ferry terminal or historic wharf below.

"That hideous concrete obscenity has blighted the cityscape for far too many decades," one resident recently told The Seattle Times, with another declaring "Seattle has quite probably the ugliest waterfront of any city in the world." In one Department of the Interior field report, researchers diplomatically allowed that "Seattle's Alaskan Way Viaduct may evoke the strongest emotions — both positive and negative — of any roadway in the country."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The viaduct is, therefore, a strange structure to feel sentimental about, much less to fly cross-country to mourn. I do not disagree with its critics; beyond its befuddling placement through two miles of the most beautiful real estate in the city, the eyesore shuttled 80 decibels worth of traffic overhead, muffling conversations below. That's not even to mention the fact that it was a death trap, looming heavily over the heads of tourists and residents as some 110,000 cars commuted across it daily. Simulations of the viaduct collapsing in an earthquake were as hypnotizing to watch as a bad disaster movie, and it seemed only through some miracle that the whole thing remained standing after magnitude 6.8 tremors in 2001.

No, the viaduct had to go, as 10 years of debates and some $325 million in preliminary research and engineering finally, exhaustingly concluded. (A last ditch effort to turn the viaduct into an elevated park, like the High Line in New York City, was shot down by more than 80 percent of city voters.) The State Route 99 replacement tunnel began its long comedy of errors in 2011, and after more than 29 months in delays, it opened on Monday to its first drivers. With that, the viaduct, closed since Jan. 11, at last became obsolete.

Born and raised in the Seattle area, some of my earliest memories are of that distinct thunk-thunk of traffic passing overhead. Later, my first journalism job would take me down through the viaduct's concrete legs as I followed the city's winding roads to and from the bus. The Alaskan Way Viaduct was such a part of life that it felt impossible to believe it would ever actually disappear. So when it was announced, after all the delays and dents in construction, that this was the final weekend to say goodbye before the viaduct came down, I secured my ticket back home, driven by some insane snap of nostalgia and loyalty, to look at it once more before it was gone forever.

I was hardly the only one; the response to its imminent demolition was overwhelming. An eight kilometer race through the new tunnel and across the overpass attracted 29,000 participants, the biggest walk/run event in the city's history. A couple from Beaverton, Oregon, drove all the way up to get married on the viaduct's top deck. Some 100,000 people ultimately turned up to walk its length on Saturday, posing for pictures and scribbling alternatively triumphant and mournful messages on the viaduct's rails in chalk and paint. In business windows along the route, signs wished the viaduct farewell: "Goodbye old friend," read one that made me immediately misty-eyed. "Ain't no lie, baby bye bye bye," sung another. "Farewell viaduct," somberly bid one more.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Part of the sentimentality came from the fact that, ironically, it was the viaduct itself that offered the best views of Seattle: the sweep of the shipping yards and wharves below, the expanse of the slate-gray Puget Sound, the distant swell of the Olympic Mountains on the peninsula beyond. If you caught your commute just right, you could see the setting sun turn the western sky tangerine and pink and deep hues of gold.

It was a democratic gift, one afforded to all the workers snaking their way home on an overpass built for pure, ugly efficiency. Now that picture of the Sound will be the exclusive purview of the million-dollar high rises along the waterfront, which, once blocked by a freeway, will now look out at one of the most beautiful scenes in all the world.

When I think of the viaduct now, in the past tense, I remember another sign I saw on Saturday: "Can you really love something if you don't let it change?" it asked. The sign made me think about how we fall in love, so unexpectedly, with our city's worst features — how thousands of people showed up for the demolition of the Kosciuszko Bridge in New York or the implosion of the Georgia Dome in Atlanta, and how a fist-sized piece of the Kingdome, where the Seahawks, Mariners, and SuperSonics used to play, is tucked away at my home in a safe space, like an urn of a beloved relative's ashes.

Part of this certainly comes from our juvenile curiosity to see things pulled down, but there is also something I'd like to think is more spiritual about bidding urban structures goodbye once their purposes have been rung out and their cement corners start to show cracks. Some part of me understands that for its 60 years of service, the Alaskan Way Viaduct deserves to be more than a cautionary tale taught to city planning students. That there was a time when you didn't know the city unless you'd seen a sunset from the freeway's upper deck.

So on Saturday, 2,000 miles from my new home, I took a minute to look out at the choppy waters of Elliott Bay. I committed to memory the low concrete guardrails, the hump of Bainbridge Island. I looked from downtown in the north toward the stadiums rising in the south. For that one instant, I held the viaduct's whole morning in my view. Then, for the last time, I stepped lightly away, leaving it to change.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.