The problem with authors writing fan fiction

The notion of canon has been forever altered, in no small part because of the creators themselves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

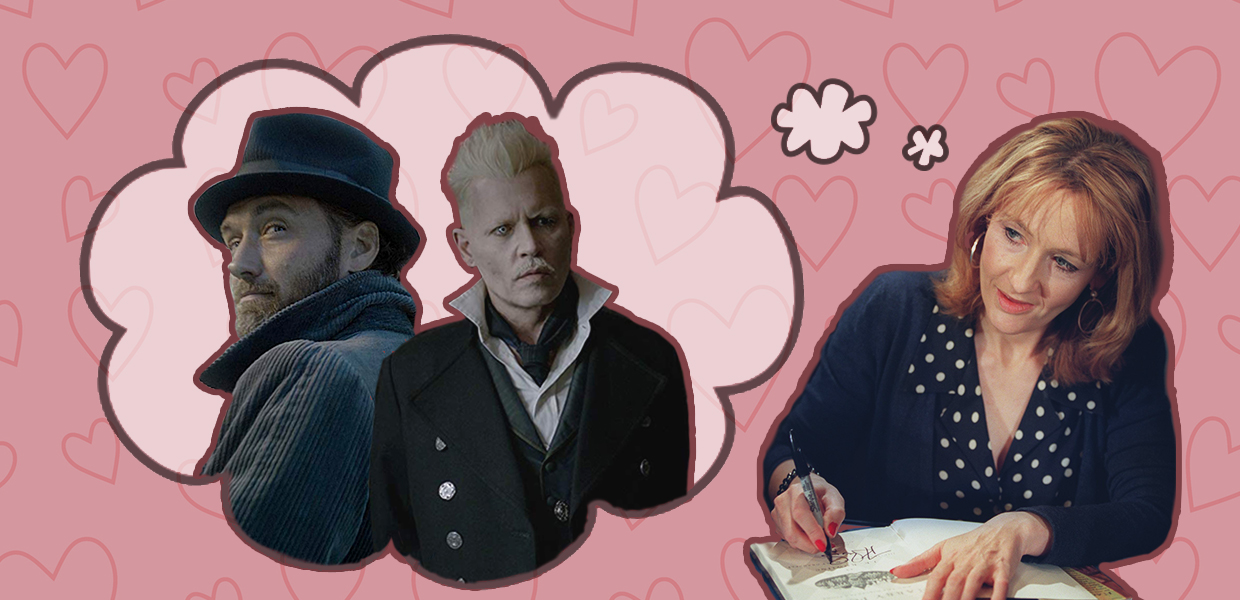

The internet was abuzz a few weeks ago after author J.K. Rowling revealed that the characters Albus Dumbledore and Gellert Grindelwald had an "incredibly intense" and "passionate" relationship with a "sexual dimension." Though this unsolicited declaration was especially bizarre and meme-worthy, it was only the latest of several years worth of post-series changes to the Potterverse. Hermione is (possibly) black, Nagini is an Asian woman, wizards don't have indoor plumbing, etc. Since the final book of the original Harry Potter series was published in 2007, Rowling's website Pottermore has become a fountainhead for excess information about the wizarding world. Conveniently, much of that information has fallen into the category of diversity, as if Rowling thought she could retroactively add queer wizards and wizards of color and pretend they were there all along. Perhaps, like the horcruxes, we just didn't know they existed until the end.

The massive wave of jokes that came at Rowling's expense after the Dumbledore-Grindelwald reveal showed how dismissive fans have become of her updates, and this isn't the first time fans have poked back at the creator. As Rowling has continued to build on her franchise, with the Fantastic Beasts films and the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, some fans have taken to being more discriminate in what they understand to be canon — the original seven books, no more and no less (well, maybe less, if you want to cut the epilogue).

Rowling is not alone. In fact, in recent years, the very notion of canon — the official, undisputed, author-sanctioned account of every event that has occurred in, and all attributes of, a fictional universe and its inhabitants — has been transformed into something so pliable to the whims of creators that it's been made fragile, something meant to be broken and disregarded. Now more than ever before, fans have taken on the position of arbiters of their fandoms, calling out disingenuous revisions and editorial fouls and taking charge of their favorite fictional universes — as very well they should.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It wasn't too long ago that canon and fan fiction — always linked but always in clear opposition to each other — were much more clearly delineated. One belonged to the creator and the other to the fans. One static and authoritative, the other fuel for ever-changing and evolving conversation but with shared agreement that it was something separate. But in the last several years, there's been an uptick in the number of creators who, by continuously editing and expanding and retroactively changing their creations, have blurred those lines. Before, the canon was the canon and was respected as such. Now it's not that simple.

Though a large part of Rowling's continued wizarding world updates must surely be commercially motivated — more movies, books, and plays means more money — another, more innocent reason might be her desire to improve the text by fixing some of the mistakes she made the first time, some of which, like the lack of diversity, have been pointed out by fans.

George Lucas, the Star Wars creator has been dragged across the hot coals of fan anger so many times it's hard to keep track. When he introduced fans back into the world of Star Wars with the prequels, he aimed to expand the universe's mythology. But that resulted in him sloppily overinflating the story, characters and the logic of the universe. The Force and midichlorians, the circumstances around Vader's rise and Luke and Leia's birth — in diving back into his universe, Lucas repeatedly stumbled over his own feet, opening his writing up for critique by fans who noticed odd additions and inconsistencies.

Though fans have come to appreciate the prequels more with time (this year being the twentieth anniversary of Episode 1), many wrote them off when they first appeared, claiming instead to be fans of only the original trilogy and refusing to acknowledge the prequels as canon.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are plenty of other examples of canon sequels or plotlines that fans have ignored or totally rejected, too: X-Men: The Last Stand, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Willow's relationship with Kennedy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the final minutes of the finale of How I Met Your Mother (an alternate ending was filmed that many fans find more satisfying), and another entry in the Star Wars universe, The Star Wars Holiday Special.

Originally, fan fiction introduced a more democratic way for people to engage with their fandom, stories inspired by the universe and characters, products of imagination and extrapolation. Some creators' work became almost synonymous with fan fiction, as though the very worlds they created outgrew them. And that wasn't necessarily a bad thing, because there was a clear line between the original works and what came after.

Fans engage with fandoms as self-contained worlds, places where we can suspend our disbelief because we connect to the characters, setting, or story. When creators ungracefully step back into those worlds, leaving their footprints all over, their changes might not stick because they don't feel native to the works as we first knew them. Suddenly we become aware of the fiction as, well, fiction. In going back, the creator may put even more of a spotlight on their mistakes the first time around, and, as in a game of Jenga, once you pull the wrong block, the whole tower starts falling down.

That isn't to say that creators can't return to their work or change anything. Back in the late nineteenth century, before gifs and memes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, sick of his famous fictional detective, tried to kill off Sherlock Holmes. But the death caused public uproar, and eventually Doyle did his own bit of narrative backpeddling, resurrecting Holmes to the excitement of his many fans. And later this year, too, Margaret Atwood will be reopening the book on Gilead more than three decades later. Though The Handmaid's Tale is a classic with a famously ambiguous ending, the Hulu TV adaptation (produced by Atwood) has been filling in a lot of the blanks in the novel, and the forthcoming sequel to the book will continue to expand our understanding of that world. How fans will react will depend on how seamlessly and logically the sequel will fit with the classic, the canon.

But perhaps the problem is larger than writers who can't bear to step away from their laptops. Our current culture is one of things super-sized, expanding, more. More sequels and spinoffs and tie-ins. More movies, TV series, video games, and books. Star Wars and Harry Potter don't just belong to Lucas and Rowling; the canon for each is more than what each writer produced, the original trilogy and the seven books, respectively. Fan universes expand so rapidly nowadays that the canon becomes large, unwieldy, constantly open to edits and excess. It makes sense that writers would want to participate in that process and go back in for another shot at their creations. But that also means that fans can pick and choose or outright reject these updates, and, in our social media age, they're going to be loud about their choices.

In the long run, maybe it's best if authors leave fan fiction to the fans.

Maya Phillips is an arts, entertainment, and culture writer whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, Vulture, Slate, Mashable, American Theatre, Black Nerd Problems, and more. She is also a web producer at The New Yorker, and her debut poetry collection, Erou, is forthcoming in fall 2019 from Four Way Books. She lives in Brooklyn.

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?