The universal pain of unaffordable child care

This isn't just a rich people problem

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It looks like doing something about child care will be a big part of the Democrats' 2020 campaign. Ideas like a national day care system have taken hold among liberals. And one of the party's major contenders, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, already has a plan to make child care affordable and more widely available.

Conservatives are not on board with this. They often view universal child care as a niche concern for well-to-do, upwardly striving two-earner couples, and a blinkered effort at social engineering: "Incentivize one way of parenting — all parties working full time, which many parents don't even want to do — while forcing other people to pay for it," as National Review Online's Heather Wilhelm put it.

Pick through the data, though, and the liberals have the better of the argument. The pain caused by America's unaffordable child care crisis isn't confined to any one class of people, it's pretty universal.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, among families with married parents, having both parents in the work force — and thus presumably needing child care in the first place — is actually much less common the further you travel down the class ladder. The Center for American Progress (CAP) released a paper last week that looked at all families with a child under 5 and a mother who works, married or not (just over five million in all); and they found the share of families who pay for child care rises significantly with income and education level. All of which might seem to back up conservatives' beefs at first blush.

But the CAP paper also has a lot of complicating details.

Three fourths of the families where the working mom has a graduate or professional degree may pay for child care, but it's still 35 percent and 39 percent when the mom has less than a high school education or just a high school degree, respectively. That's a lot of families. Forty percent of families making less than twice the federal poverty level (FPL) for a family of four pay for child care. That's less than the 76 percent of families making over six times the FPL, but it's still significant.

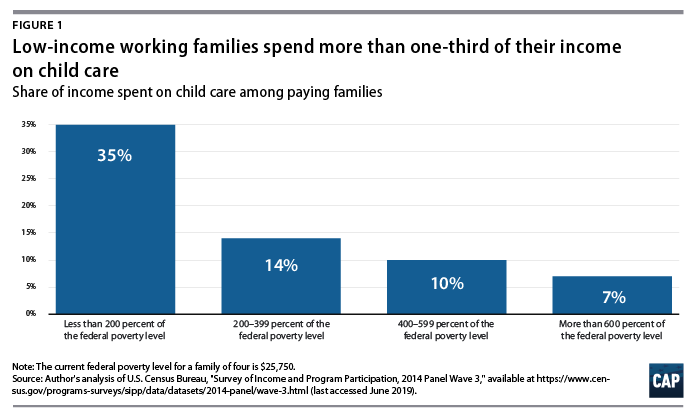

More to the point, even if lower class families use child care comparatively less often, their household budgets get absolutely brutalized when they do. The families where the working mom has a high school education forked over 14 percent of their monthly income to pay for child care. For less than high school, it was 17 percent, and for families making under twice the FPL — a third of all the families that CAP looked at — it was a whopping 35 percent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To give you some context, the Department of Health and Human Services considers seven percent of income to be the upper threshold of affordability. Even the families in the highest education and income groups CAP looked at were spending 7-to-8 percent of their income — barely within the range of affordability. For all 5.1 million families with a child under 5 and a working mom, the average payment was 10 percent of their income a month.

The pain of the child care affordability crisis, in other words, is widely shared up and down the class ladder.

It's also a crisis that really is driven by the basic structure of the modern American economy: Inequality is yanking costs of living higher for everyone, even while middle-class wage stagnation forces more parents to work to keep up. That cities have become the economy's sole islands of job creation is packing more and more people into the places where this ratchet effect is the most intense. Meanwhile, child care itself isn't really amenable to economies of scale or to new efficiencies through technological innovations, which puts a hard floor under how much the service costs, even with child care providers paying their employees paltry sums. Often times, it's lower-class American families who are smashed the hardest between the hammer and the anvil: Getting the second parent into the labor market is the only way to raise their incomes, but they can't because the cost of child care remains stubbornly unaffordable.

Conservatives complain that subsidizing private child care providers, as Warren's plan would do, simply makes the cost problem worse. But this ignores that all the economic logic that powers the affordability crisis exists whether we subsidize or not.

The real problem with subsidizing is arguably that it doesn't challenge that underlying economic logic. That's also a problem for conservatives own preferred solution — a more generous child tax care credit. It's even a problem for a universal child allowance, which is better than a tax credit because it isn't tied to work and doesn't require recipients to jump through the hoops of the tax code to get it. All of these ideas basically amount to throwing money at the problem, without altering the market structure at work, and hoping everyone can keep up.

That's really the argument for direct government provision of day care and child care. The crisis is driven by how private providers are caught between the need to make a profit and the fact that even really low pay for their employees still leaves child care brutally expensive for the everyday family. There's only so much blood you can squeeze from the stone. The federal government could hire enough providers to provide everyone quality service, and pay them good salaries, without having to worry about making a profit or even breaking even.

We should certainly endeavor to make America's child care system as fair and neutral as possible for families of all sorts; for moms and dads who both want to work, and for moms (or dads) who want to stay home. For example, a recent proposal by the People's Policy Project would combine direct government provision of child care with a universal child allowance, and an extra top off on the allowance for families who choose not to make use of child care.

But the child care crisis isn't just a crisis for liberals who believe women should have equal access to the labor force. And it's not the sort of thing that merely a more well-designed tax credit can solve.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney