What lockdown drills mean for my 1st-grade classroom

When the alarm sounds, a teacher's job is to be clear, comforting, and honest

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Lockdown drills are commonplace in America right now because of the horrific reality of school shootings. Whether they ultimately help our children is still up for debate, but one thing is for sure: We have to do them right when we do them at all. And doing them right means being honest, calm, loving, reassuring, and protective. That's a teacher's job, after all.

I'm a teacher, and I vividly remember one lockdown drill I facilitated with my students. They were first-graders, 6 and 7 years old, and this drill took place at the beginning of the year and wasn't intended to be a surprise. I put it on the daily schedule on the whiteboard, and we discussed it plainly at our morning meeting.

"Why are we doing a lockdown?" someone asked me.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I used to answer this question vaguely (and, quite frankly, dishonestly). I'd tell the kids we were protecting ourselves in case a dangerous animal came onto campus. I know other teachers who have done this and it's easy to understand why: Kids love animals, they're less scary than people, and there's a sense of mystery and even adventure in imagining some creature roaming the grounds.

But this is a disingenuous way to frame such a drill. And animals roaming the school can be a scary thought, too. The truth is that even young kids know what we're doing in these drills: We are practicing what to do if someone comes into the school to kill us. Students might not always say it, but they know. And even if they don't know the horrible details — that the weapon will be a gun, that it will most likely be wielded by a radicalized white male, that it will probably be 1,000 times more terrifying than anything they've ever experienced — they know something is deeply amiss.

So this time, when this child asked me why we were doing a lockdown drill, I answered more directly: "In case there's a dangerous person in the school somewhere, when we hide and turn off the lights, that person will think the room is empty." This may not be entirely true, but it serves its purpose while also being honest enough to pass muster.

"But what if they get in?" the student asked. And this is the tricky part: Sometimes kids need specifics. "What do they want to do with us?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"We have amazing security guards," I said, "who have been trained to stop people from coming in."

"But why do they want to hurt us?"

The kids gave me the type of undiluted, complete attention that I wish they'd use for math lessons. It's incredibly difficult to articulate to kids why a sick man would want them dead.

So I said this: "It's ok to feel scared and confused. I will be here the whole time, alongside you, and ask me for anything you need. We are together, and I know what to do. I don't really know why someone would want to hurt us, but what's important is that we are in the safest place in the school. We have done everything a school can do to be safe and protect ourselves."

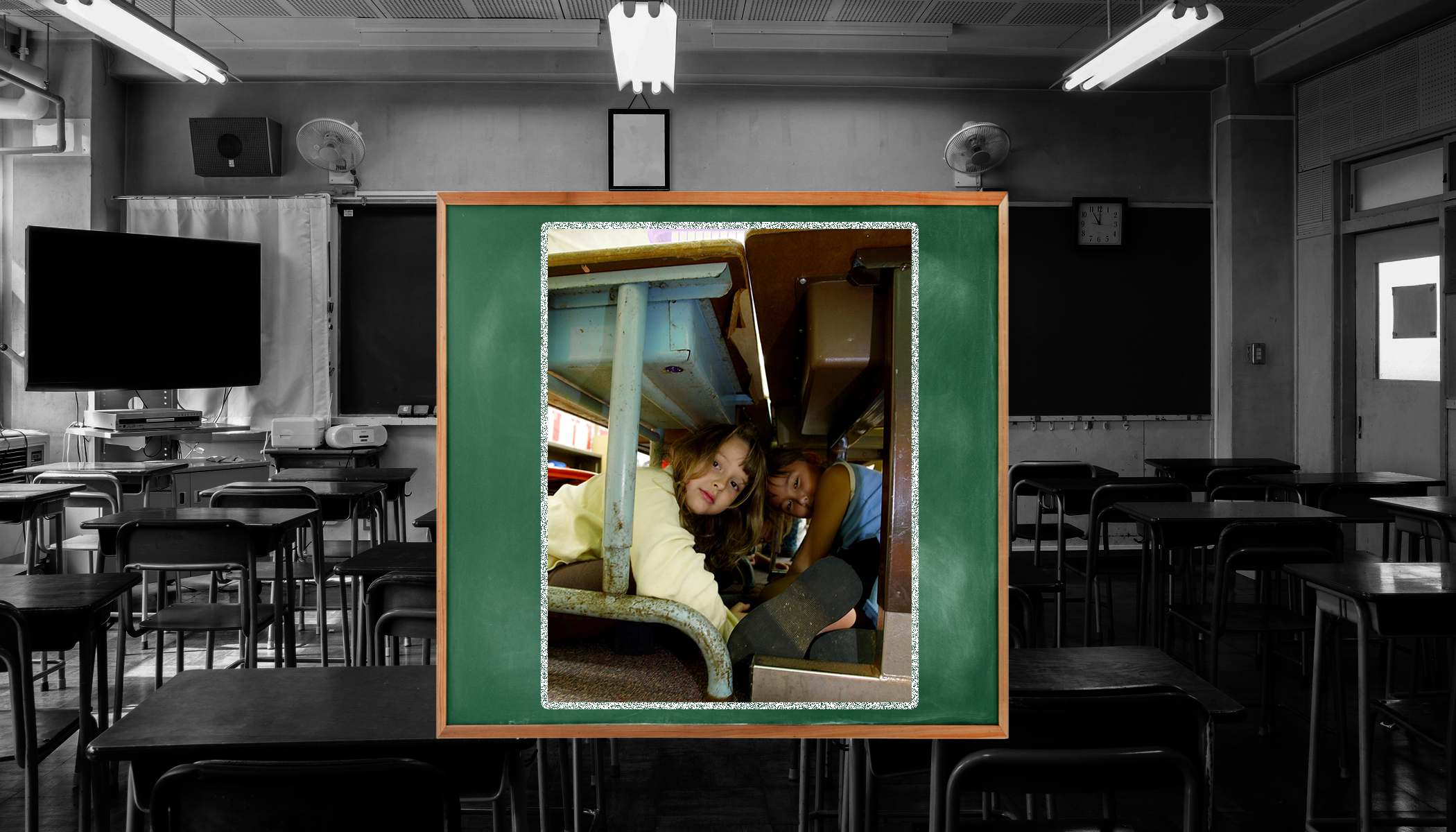

Later that morning, the alarm sounded, and the kids filed into the large bathroom in the corner of the classroom. I closed the blinds, turned off the lights, and locked the doors, then joined the kids. There were nervous giggles. Some kids forgot to be quiet. After all, expecting kids to crowd around a toilet and be totally chill about it is unreasonable.

I took out a picture book and, as we'd rehearsed earlier, I did a "silent picture walk." I flipped the pages, pointed to different parts of the drawings, made faces, and, essentially, read them a book without actually reading it. It's an excellent way to pass the time silently, and it honestly doesn't matter what the book is — kids think the experience is unique.

When the voice came through the P.A. announcing that the drill was over, we spilled out of the bathroom. A girl came up to me and said:

"Was there actually a person out there?"

"No," I answered. "This was a drill."

"What's … a drill again?" she asked, and I realized — not for the first time — that assuming kids know all of our strange adult conventions is always a mistake. A mistake that could, in some cases, make kids think they're living through an actual emergency.

"A drill means it isn't real. It's practice."

"Oh. Okay!" she said, and skipped away to recess. I sighed with relief.

We don't really know the long-term effects lockdown drills have on children. When done poorly — and maybe even when done thoughtfully — they can cause trauma and make kids fearful of attending school. But if a school or district is going to do lockdown drills, they are an opportunity to show students that teachers and other adults at school are there to protect them. We are their guardians, their keepers. There is literally not a single thing more important to us than these kids' safety, and they should never doubt that. Sometimes I even tell kids "it's even more important than math or reading."

"What about handwriting?" a cheeky kid once asked.

"It's close," I said, "but safety still wins."

"You should pay closer attention to my handwriting," he replied. "It's beautiful."

It was beautiful. And his lovely penmanship should be more important than cowering in a bathroom, pretending someone wants to shoot bullets into us. As teachers, we can provide honesty and clarity paired with a thick mantle of safety, even if it really is a thin veneer, because ultimately there may be nothing more loving than true comfort.

Bret Turner is a first-grade teacher, father, and children's musician. He is a contributor to PBS Kids and Teaching Tolerance, he's a sourdough bread baker, and has a three-legged dog. You can find more of his writing here.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’