Is rich people's excessive income about to strangle the economy?

An economy is healthier when the working class gets a fair share of national income

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

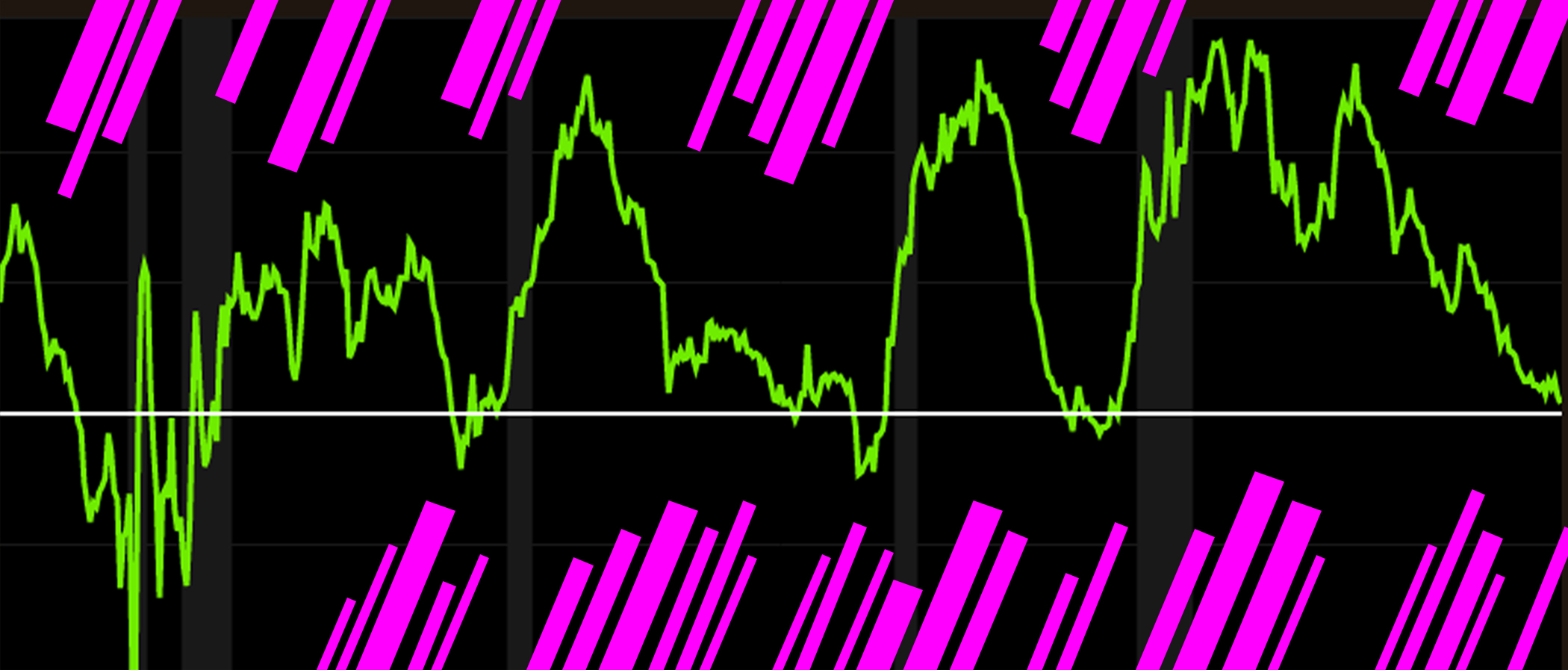

There is an economic warning sign which has gone off before every recession going back to the 1960s (and only delivered one false positive). It's called a yield curve inversion — and it just happened on Wednesday. Gulp.

Now, this doesn't guarantee a recession, of course. Even going back that far, we're only talking about a sample size of seven. But it certainly suggests there's a decent likelihood of another downturn happening soon. And while there would be many factors behind it if it does happen, there is one big one that can't be ignored: Rich people have too much dang money.

Briefly, the classic yield curve inversion is when the yield (that is, the interest that is paid to bond buyers) of a 10-year U.S. government bond goes below that of a 3-month bond. This is quite odd — typically investors receive a higher return for a longer-term loan, because they are taking on a greater risk — and it tends to indicate that investors are fleeing to safety, trying to lock in a half-decent return on their money before everything goes pear-shaped. (Incidentally, stocks were in the toilet Wednesday morning.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

However, as James Mackintosh points out at the Wall Street Journal, in most previous inversion events other types of bonds inverted too — the 10-year under the 5-year, and the 30-year under the 10-year — which hasn't yet happened. As Bloomberg's Joe Weisenthal supposes, it might just be a bond market signal that the Federal Reserve should cut interest rates.

At any rate, it is definitely the case that the U.S. economy is rather wobbly, along with most of the rest of the world. The eurozone — which never fully recovered from the Great Recession — is struggling, and regional keystone Germany is actually in recession. Trump's flailing trade war with China seems to have done little except harm both countries, and a bunch of bystander nations to boot.

Another thing Trump and the GOP have done is dump a giant pile of money on rich people with tax cuts, further exacerbating U.S. income inequality (which was already horrible). And all other things being equal, greater inequality means a weaker, more vulnerable economy.

The reasons are threefold. First, rich people spend a smaller fraction of their income, which saps demand for goods and services. Second, lack of broadly-distributed spending power means less prospect for profitable investment — why start a new business when most people's budgets are already tapped out? (As Matt Stoller argues, the investment problem is further exacerbated by galloping monopolization in most markets, which makes it all but impossible for new businesses to compete with existing behemoths, even if there are plenty of potential customers.) Finally, the one way the masses can keep up their consumption is by borrowing, which of course can't go on forever — and when the economy does hit a rock, the ensuing recession will be much worse as the whole population struggles to escape a big debt overhang at the same time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As economist John Kenneth Galbraith argued, one of the factors behind the great crash of 1929 was the "bad distribution of income." The top 5 percent of Americans accounted for about a third of income in those days, and as a result:

This highly unequal income distribution meant that the economy was dependent on a high level of investment or a high level of luxury consumer spending or both. The rich cannot buy great quantities of bread. If they are to dispose of what they receive it must be on luxuries or by way of investment in new plants and new projects. Both investment and luxury spending are subject, inevitably, to more erratic influences and to wider fluctuations than the bread and rent outlays of the $25-week workman. [The Great Crash]

Today the share of income going to the ultra-rich is about as great as it was in 1929.

Chester Bowles, the former head of the Office of Price Administration in World War II, argued brilliantly that the bedrock cause of the Great Depression was "lack of sufficient money in the pockets of Mr. and Mrs. Average Citizen[.]" In the '20s productivity and profits soared, but wages did not (sound familiar?). Eventually investment in new homes and factories sagged, and the rest of the vast corporate pyramid — built without a sound foundation of working-class consumption — caved in on itself.

If ever it has been demonstrated that prosperity cannot continue unless enough income is being distributed to all of us — farmers and workers as well as businessmen — to buy the increasing products of our increasingly efficient system, it was demonstrated in the twenties. If we need any demonstration of the fact that our economy can choke itself to death on too many profits, the twenties provide that demonstration. [Tomorrow without Fear]

A recession is coming, whether tomorrow or some future date. When that comes we should remember that a colossally top-heavy income distribution is a serious threat to our economy and take steps to fling money down the ladder.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day