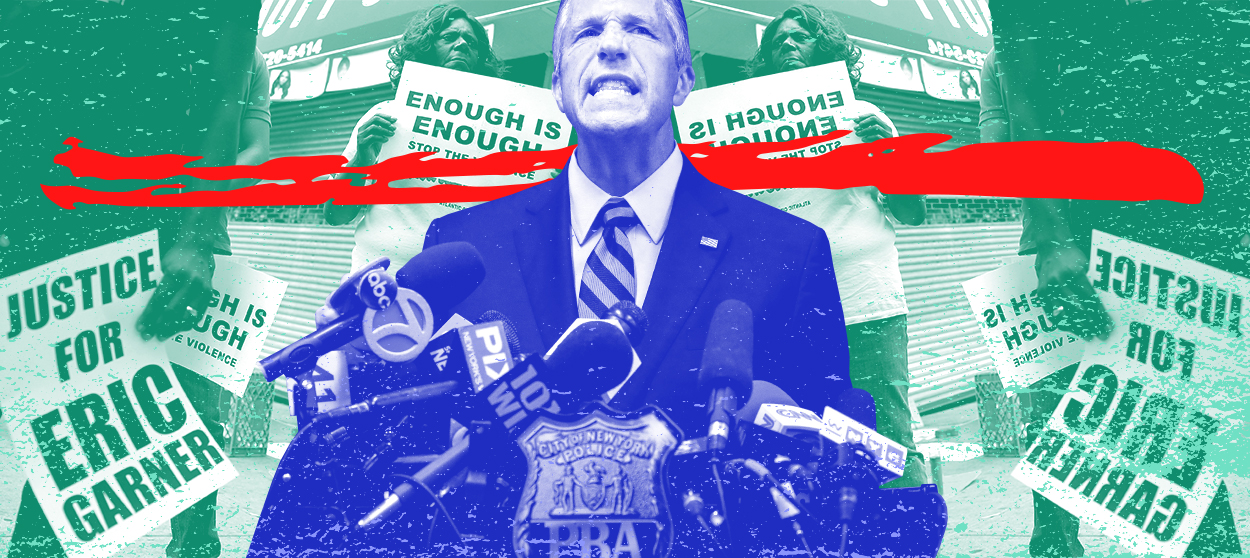

The unjust power of police unions

After Eric Garner, it's time for police reform

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

To hear Police Benevolent Association President Patrick Lynch tell it, New York's rank-and-file are the real victims in the Eric Garner case.

On Monday, Officer Daniel Pantaleo was fired from the New York Police Department. An administrative judge earlier this month ruled that Pantaleo was reckless when he used a chokehold to subdue Garner in the summer of 2014. Garner's death was caught on viral video, as were his complaints that he couldn't breathe as police brought him down. Pantaleo's firing, after five years of investigations and inaction by city leaders, struck many observers as long overdue.

After the firing was announced, though, Lynch went before the news media to express his rage and victimhood.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Our police officers are in distress, not because they have a difficult job, not because they put themselves in danger, but because they realize they are abandoned," he lamented. Lynch even seemed to hint that New York officers should stage a work slowdown in response to the firing. So much for "protect and serve." If there was a chance that Pantaleo's firing might offer some measure of healing in the Garner case, Lynch's news conference effectively wrecked it.

It was an ugly but unsurprising moment. Police unions like the PBA are great at protecting the jobs of rogue and subpar officers. That leads them to resist accountability in matters like Eric Garner's death, which means they are often destructive to the necessary task of building trust between those officers and the communities they serve.

This isn't just a New York issue.

In 2017, The Washington Post reported that more than 1,800 officers in the nation's largest departments had been fired for misconduct over the previous decade — and that thanks to protections offered by union contracts, more than 450 officers got their jobs back. In Philadelphia, a 2013 report revealed that 90 percent of officers fired for cause — for cases involving matters as seemingly clear-cut as shoplifting and sexual misconduct — had been restored to duty after arbitration, usually with full benefits and back pay.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"It's very hard to maintain discipline in a police department especially when at every turn you have cases that wind up getting overturned, people brought back, and in many cases for some very, very serious allegations," Philadelphia's then-Commissioner Charles Ramsey fumed at the time.

That lack of accountability can be dangerous. One recent study found that when Florida sheriff's deputies secured the right to collectively bargain, for example, violent incidents increased by 45 percent.

Police officers are like any other workers in the public and private sectors. They deserve to be protected from the whims of their employers. Some of the first police unions were created a century ago because officers were underpaid, overworked, and subject to terrible working conditions.

Over time, though, police unions have become powerful players in their local political scenes. Their endorsements can make or break candidates for local government office, and their opposition can stop criminal justice reform efforts in their tracks. In return, those candidates — once elected — are often overly deferential in negotiating contracts with those unions. By one count, more than half of more than 600 contracts reviewed by scholars give police unions the power to select the arbitrators who will decide if an officer firing sticks or not. That leaves even reform-minded municipal and departmental leaders nearly powerless to clean house.

Reform is possible, however. Police unions are able to avoid accountability for their members thanks to their political power. The answer, then, is also political. Communities have to generate grassroots political movements that are just as capable of putting pressure on the municipal officials who, ultimately, give their approval to police contracts.

That's what happened in Austin, Texas, where activists campaigned for more than a year to improve the police disciplinary process. In November, the city council there approved the creation of a new Office of Police Oversight with new and expanded investigative powers that advocates say could make Austin's police department one of the most transparent in the country.

"Police union contracts are ripe for reform because so often accountability, transparency, and oversight are tied up in them," the Austin campaign's organizers wrote in an April op-ed in The New York Times. "Yes, the process can be long and taxing, as we know. But the rewards are substantial."

Policing in America isn't easy or safe. It's just been a week, for instance, since six Philadelphia officers were shot in a single standoff. The public, though, has a vital interest in ensuring its police officers are competent and honest — and in reducing the number of cases, like Eric Garner's, where suspects are injured or killed. Old union pros like Patrick Lynch will no doubt oppose the accountability process every step of the way. But getting there is possible.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

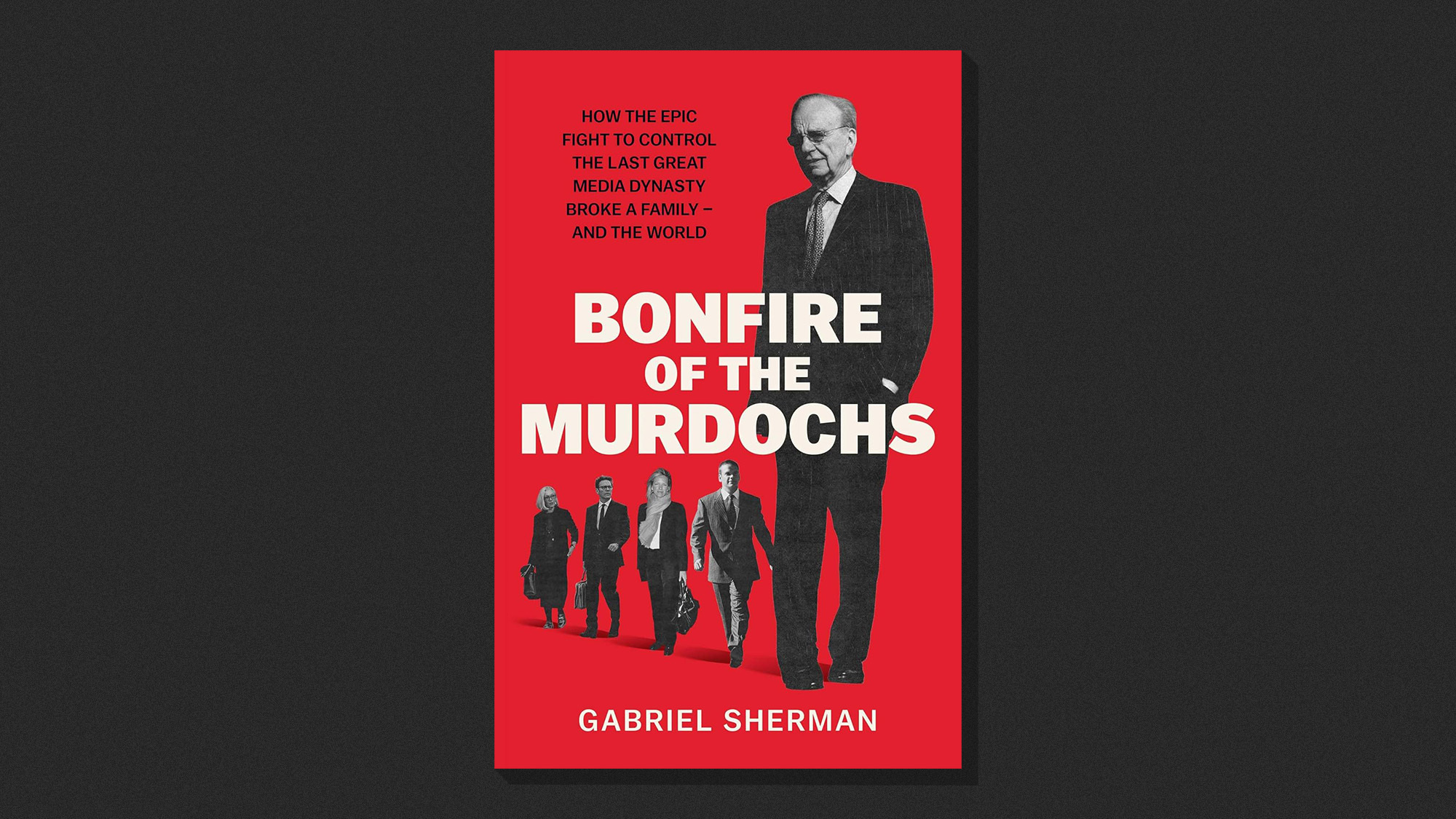

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

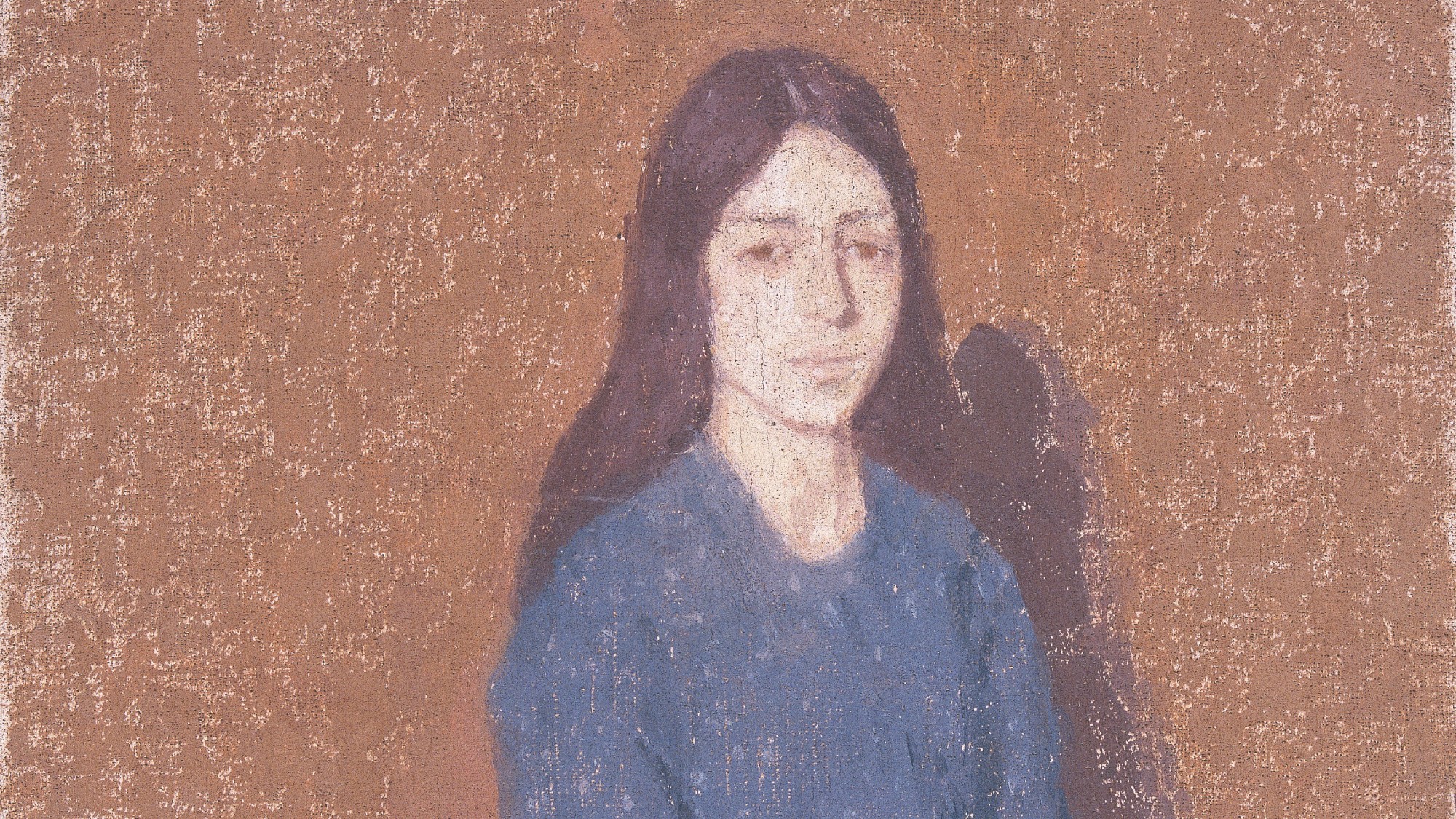

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed