The rootin' tootin' life of T. Boone Pickens

The billionaire, who died Wednesday at 91, was one of those extraordinary figures who seems to exemplify the strangeness of the American character

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

T. Boone Pickens, who died on Wednesday at the age of 91, was one of those extraordinary figures whose life seems somehow to exemplify the strangeness of the American character. Even his name seems impossible, something from a caricature.

Pickens was born in rural Oklahoma in 1928, on the eve of the Great Depression. The story of his early years might well have been written by Horatio Alger. His father worked in the oil business and his mother was employed by the wartime Office of Price Administration, where she was in charge of rationing, among other commodities, petroleum. He spent his childhood doing the sorts of things one expected of children in rural America back then — handling various chores for his aunt and grandmother, who lived next door; delivering papers; participating in the Boy Scouts; playing sports; and becoming a proficient clarinetist.

After graduating from high school, Pickens briefly attended Texas A&M before transferring to Oklahoma State University (then Oklahoma A&M), where he earned a bachelor's degree in geology. After graduating he was employed for a time by the old Phillips Petroleum Company. He became a wildcatter in 1956, in the heady days when the memory of Thomas Baker "Dry Hole" Slick, a onetime failed "lease man" who discovered what was then the largest oil field in Oklahoma in 1912, was still fresh in young imaginations.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Two and a half decades later, Pickens' Mesa Petroleum was one of the world's largest independent oil outfits. Pickens began acquiring other firms, using a practice, he later claimed, he had first discovered as a paper boy, when he pushed other boys out of their routes, expanding his deliveries from 28 to 156.

There is no use pretending that Pickens' business career is worthy of celebration. His corporate raiding in the 1980s exemplified something new and vicious in the attitude of American businessmen that would mean the final destruction of the old pragmatic post-war consensus on the carefully regulated mixed economy. It is a small comfort that he devoted a considerable amount of his sometimes ill-gotten gains to the quixotic cause of Oklahoma State Cowboys football, donating more than $265 million to the athletic department. (Statues of both him and Barry Sanders stand outside the 55,000-capacity Boone Pickens Stadium.) Well-meaning liberals grumbled at the time that the money ought to have been put to better use, but one suspects that at some level he recognized that what he had gained fortuitously ought to be spent on something frivolous. This seems to me very wise.

Pickens's own political views were often surprising. He had few fixed principles. His mind ran on a bizarre admixture of prejudices, and sentimentality. The same man who did more than anyone else to drum up the ridiculous "Swift boat" controversy during the 2004 election was also a great lover of animals who devoted considerable resources to attempting to ban the butchering of horses. (In this campaign he was joined by a far-flung group of allies that included Bo Derek and Willie Nelson.) After Hurricane Katrina he and his company BP (Boone Pickens, not British Petroleum) gave some $7 million to relief efforts; at his own expense he had numerous planes chartered for the express purpose of rescuing stranded dogs from the flooding. He gave millions to hospitals, parks, YMCAs, and medical research institutions.

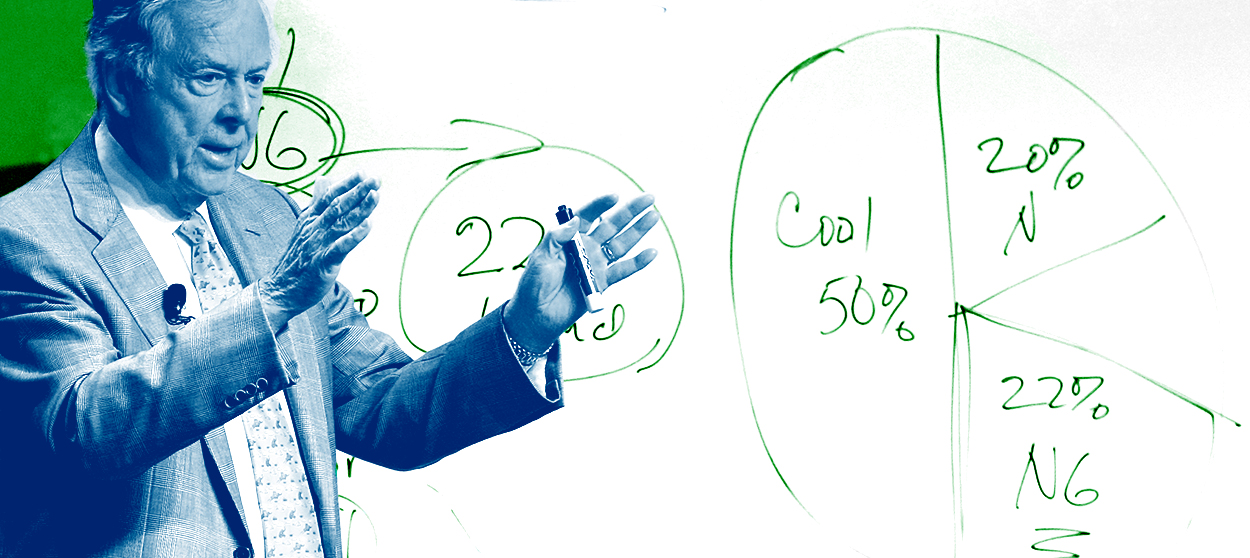

But the most remarkable development in his political evolution came in the late 2000s, when Pickens became convinced of the peak oil hypothesis and became an advocate of alternative energy. In 2007 he began construction of — it could not have been otherwise — the world's largest wind farm in Texas. This project was eventually stalled, but he didn't abandon his advocacy. The next year he released the so-called "Pickens Plan," a kind of Green New Deal avant la lettre which was endorsed by, among other individuals and groups, Michael Bloomberg and the Sierra Club. It called for $1 trillion to be invested in alternative energy, and he spent nearly $60 million promoting it with a then-novel social media advertising campaign and appearances on Jay Leno and The Daily Show.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Was there a mixture of self-interest and humanitarianism in all this? Almost certainly. At the time there was probably no one in the country who stood to benefit more financially if the Pickens plan had been adopted. But there was also, I think, a sincere attempt to grapple with the profound human and ecological costs of everything that made Pickens wealthy beyond reckoning. He was a very greedy man, but undeniably a generous one as well.

Everything about Pickens — his long and adventitious career, his shifting viewpoints, his idiosyncratic personality, his quiet but unmistakable agnosticism about the realities of capitalism — reminds us that the American people are, for good or ill, utterly unlike any other.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention