Stanley Fish's 6 essential reads

The literary theorist recommends works by Thomas Hobbes, Ford Madox Ford, and more

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

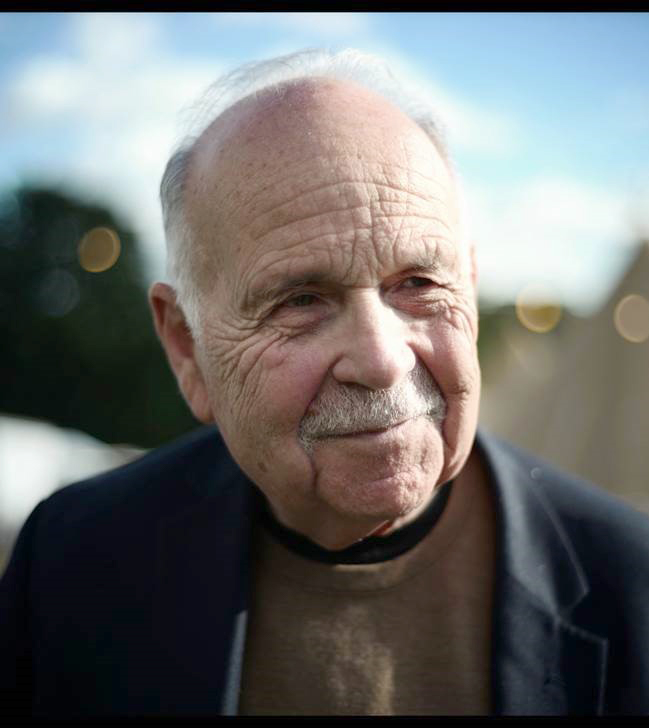

Stanley Fish is a prominent literary theorist and legal scholar whose books include How to Write a Sentence. His latest is The First: How to Think About Hate Speech, Campus Speech, Religious Speech, Fake News, Post-Truth, and Donald Trump.

Paradise Lost by John Milton (1667).

Any question anyone has ever had about anything — creation, life, death, salvation, astronomy, heroism, faith, sex, marriage, history, science — is posed and plumbed in this supreme achievement of mind. Paradise Lost reads you.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Pilgrim's Progress by John Bunyan (1684).

This is at once the ultimate quest story and a psychological primer deeper than Freud's. Bunyan's hero becomes aware that he shoulders an unbearable burden (it is original sin), and his efforts to rid himself of it are thwarted when his fears and anxieties take external form and attack their host.

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford (1915).

A story that's chock-full of monstrous betrayals is narrated by a participant who understands nothing of what has happened. "Empty" is too full a word for him. The maintenance of this personhood-free persona is extraordinary and unmatched in any novel I know.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How to Do Things With Words by J.L. Austin (1962).

Austin posits a firm distinction between language that mirrors the world of fact and language that creates the facts to which it then refers. But his book-length search for criteria to outline that distinction fails. The implication (which Austin would resist) is that our words never quite match up with the thing we call reality.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn (1962).

For the traditional picture of scientific work as cumulative — generations of scientists adding to an increasingly precise account of nature — Kuhn substitutes one in which scientific descriptions follow from assumptions and methods currently authorized by the profession. When change occurs, it is because a paradigm has been dislodged and replaced. Humanists love Kuhn and Austin, because they provide a defense against the charge that literary and historical interpretations are not grounded. In Kuhn's wake, they can say that nothing is.

Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1651).

A deeply undemocratic message, delivered in some of the best English prose ever written. Knowledge, to Hobbes, was conditional upon man-made conventions that set the terms of what can be said. Preserving peace requires hewing to those conventions. Otherwise, pluralism, and chaos, ensue.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day