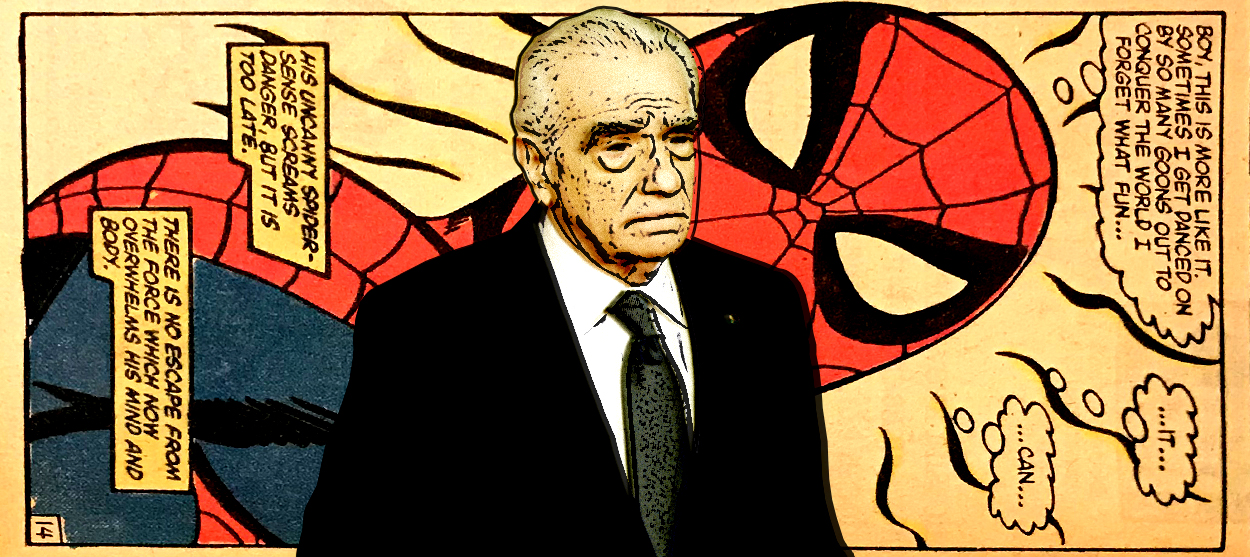

Martin Scorsese is right. But it's not just a Marvel problem.

The Irishman is as much a product of capitalism as The Avengers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It has been over a month since Martin Scorsese, intentionally or not, declared open war on Marvel. In early October, the director — on tour for his first Netflix film, The Irishman — told the British film magazine Empire that comic book movies are "not cinema," dismissing the multi-million dollar industry as making, essentially, "theme parks" rather than "the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences."

In the weeks that followed Scorsese's remarks, all hell broke loose: Francis Ford Coppola jumped on the pile to call Marvel movies "despicable," legions of people who watched and enjoyed such films as Thor: The Dark World "canceled" Scorsese, and Disney head Bob Iger passive-aggressively announced he'd like to have a "glass of wine" with the Goodfellas director but that "I don't think he's ever seen a Marvel film."

In an attempt to clarify that no, he really, truly hates Marvel movies, Scorsese published a New York Times op-ed on Monday bemoaning "a perilous time in film exhibition," which has left Americans fewer and fewer choices of what they can see at their local theater. Scorsese identified this as a feedback loop where consumers don't even know to want anything other than Marvel anymore. "That's the nature of modern film franchises," he wrote, adding that such products are "market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted, and remodified until they're ready for consumption."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But while Scorsese gets a lot right about Marvel and the modern movie industry, what he gets glaringly wrong is his implicit suggestion that streaming services like Netflix aren't doing the exact same thing.

Speaking personally, I can get on board with the core of Scorsese's argument: that there is rarely "revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger" in modern franchise films, which are formulated to break box office records and rake in as much money as possible for studios (I'm not a cynic: just look at the number of directors who have left Marvel projects, citing aggressive studio oversight hampering their vision). Still, arguing about what constitutes "true art" is not only futile, it's frankly a boring variation of a conversation cultured intellectuals have been having for hundreds of years. Far more interesting is Scorsese's observation that "in many places around this country and around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen."

It's true that outside of major cities, it can be near impossible to see the kinds of arthouse, independent, foreign, or classic films that Scorsese undoubtedly considers "cinema." (It bears noting that Scorsese wishes such movies were the blockbusters of our time, the way Hitchcocks' were of his; for a variety of reasons, that ship long ago sailed and will not be returning to the harbor). Part of this is owed to studios flexing the demands they can get away with putting on theaters: Disney, as one recent example, strong-armed every exhibitor that wanted to show Star Wars: The Last Jedi into agreeing to wildly restrictive terms, including that the movie be shown in the theaters' "largest auditorium for at least four weeks," The Wall Street Journal reported. Such a hostile theatrical climate led directors asked by The New York Times earlier this year if there is a future for showing anything besides blockbusters in cinemas to despair. "I don't feel particularly optimistic about the traditional theatrical experience, especially for independent films," La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz said, echoing many of his colleagues' sentiments.

Recently, reports have also emerged of Disney refusing to allow theaters to screen any of their older titles, including the 20th Century Fox catalog now in its possession. Explained the Times, "There's a clear business rationale for Disney to create scarcity. The company is counting on the combined library of Disney and Fox films to draw subscribers to its upcoming streaming service Disney+, which launches [Nov. 12]."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Scorsese's primary argument has to do with these restrictions; that the country has a shrinking number of screens that can financially justify showing something other than the 17th reboot of Spider-Man. "But, you might argue, can't [people] just go home and watch anything else they want on Netflix or iTunes or Hulu? Sure — anywhere but on the big screen, where the filmmaker intended her or his picture to be seen," the director writes in his op-ed. But Scorsese's faith in streaming as a substitute, if not quite replacement, for the movie theater is misplaced.

For one thing, it is streaming itself that is destroying the ability for people to watch the films he considers art: Disney+ is the reason for Disney's clampdown on the titles in its vault. What's more, Netflix and other streaming services rarely offer "movies older than a college student," in the words of Film School Rejects, which notes: "Of the 1,350 drama titles [available for streaming on Netflix U.S. in 2017], only 97 were released prior to 2000. Even if we consider 1920, the year when the oldest of these films (The Daughter of the Dawn) was released, the 'starting point' — that is, not even going back to the late 1880s/1890s, when film was first invented — then 82 percent of film history is represented in a measly 7 percent of streaming Netflix's drama library."

Even more misleading, though, is Scorsese's rave that Netflix "alone allowed us to make The Irishman the way we needed to." That's not to say Netflix didn't — when I saw Scorsese speak at the New York Film Festival press conference, he addressed how Netflix was the only studio willing to fund the expensive, complicated, cutting-edge cameras that allowed the director and his crew to digitally "de-age" the actors. But Netflix's decision to get behind Martin Scorsese's new movie was as calculated as any made by Marvel over the years. It is good business to win an Oscar in a major category, something Netflix is clearly lusting after. Additionally, the streamer bagging a Scorsese flick makes fools of the few dusty institutional holdouts of the streaming era, like the prestigious Cannes Film Festival, which still does not allow Netflix movies in competition. And while Scorsese praised Netflix for allowing his film "a theatrical window," the fact that The Irishman is in theaters likely has more to do with it still being a requirement for submitting to the Oscars than anything else.

Scorsese's main charge against Marvel is that its pictures are rendered sterile and uninspiring by the capitalist process of market-research, audience-testing, and vetting to make the best consumer product possible. But there is perhaps no greater villain than Netflix when it comes to relying on data and algorithms to decide its programming. It is Netflix, after all, that has produced terrible Adam Sandler movie after terrible Adam Sandler movie because they do really, really well with home viewers. The streamer has also canceled beloved, critically-acclaimed shows just for failing to garner the requisite number of eyeballs. Netflix — like Marvel — is a company first and foremost, and its ultimate concern is its bottom line, not some altruistic respect for art.

Of course, excoriating streaming without any qualification isn't fair either; there are a number of services out there that attempt to offer an alternative to the norm, like the wonderful Criterion Channel or my personal favorite, Mubi. Such services — as well as the controversial but growing acceptance of pirating otherwise unavailable and out-of-print films — are exactly the access that allows people who live in cinema deserts to appreciate movies as more than just celebrities phoning it in while wearing Spandex costumes. Yet these smaller streaming services, just like America's arthouse and rep theaters, are fighting an uphill battle against giants like Netflix, Amazon, Apple, and soon, Disney, for viewers — and doing so without the ability to throw money at original projects by big-name directors like Scorsese. Filmstruck, a predecessor to the Criterion Channel, lasted only two years before it was shuttered by AT&T; another independent streaming service, Fandor, faced layoffs in late 2018 and today is a shadow of its former self.

As Scorsese notes of Marvel, "It's a chicken-and-egg issue. If people are given only one kind of thing and endlessly sold only one kind of thing, of course they're going to want more of that one kind of thing." And if people in America's growing regions without repertory and arthouse cinemas can't find the likes of Scorpio Rising and Strangers on a Train online either, at this point how would anyone know any different?

It's a vicious cycle, which — short of ending capitalism itself — has no clear solution. It is why Scorsese ultimately finishes his op-ed on a pessimistic note: "For anyone who dreams of making movies or who is just starting out, the situation at this moment is brutal and inhospitable to art." And unless your name is Martin Scorsese, streaming will be no salvation either.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.