Little Women puts Jo March's writing dreams at the center of the story

How one of Greta Gerwig's biggest departures from the book manages to feel authentic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

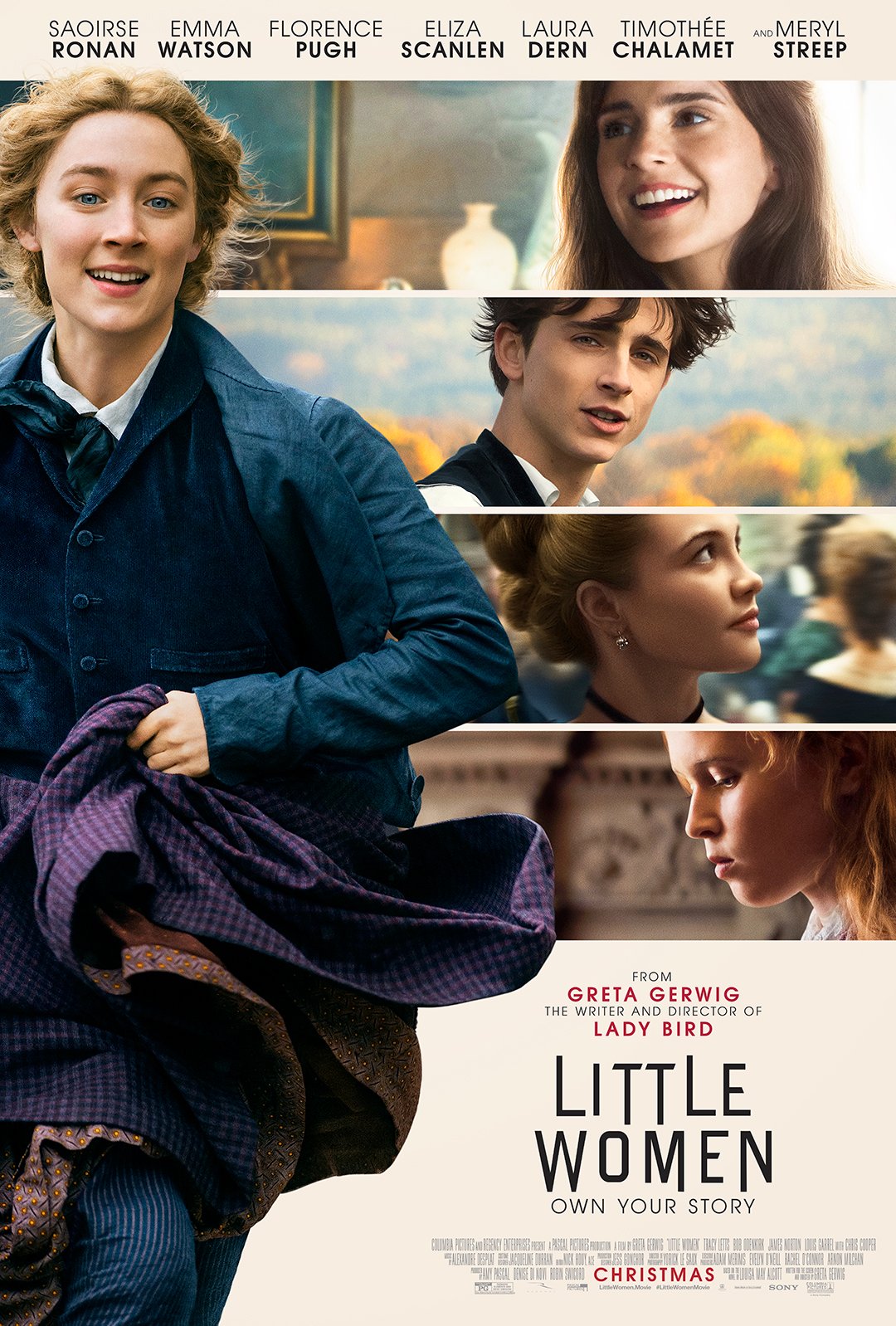

Everything you need to know about Greta Gerwig's adaptation of Little Women you can learn from the font. When the initial artwork for the movie was released this fall, fans were struck by the odd choice of lettering on the poster: a narrow and tall sans-serif font with uneven leading, which seemed out-of-step with 2019's otherwise bold movie typefaces.

The Little Women font wasn't a design firm's misguided attempt at something quirky and feminine, though. It was, rather, the exact same font used on the first edition covers of Louisa May Alcott's novel when it came out in 1868. The choice to conflate Little Women (the book) with Little Women (the 2019 adaptation) doesn't stop at the font, though; in an enormous and significant departure from the novel, Gerwig has her protagonist, Jo March (Saoirse Ronan), author Little Women herself in the movie as a sort of Alcott stand-in. It's a not-terribly-uncommon framing device that has been used by many other directors — often coming across as trite and lazy. But in this case, the change fits, elevating Alcott's original story from being one about unfulfilled artistic ambition, into one, uniquely, about craft.

When I was an impressible pre-teen, Jo March was my hero, as she was to many would-be writers. The literary sister in the March family, Jo aspired to be an author only to be cruelly admonished by Professor Bhaer, her eventual husband, for writing "thrilling" stories he considered to be trash. Jo eventually concedes he's right and burns her work; later, "[w]hen the professor shows up in Concord to declare his love, Alcott utterly abandons Jo's passion for writing," explains Hillary Kelly for Vulture on why the original Little Women wasn't exactly the wildly feminist novel it is often remembered as being. Gerwig, thankfully, doesn't let Jo reach the same miserable conclusion; instead, she blurs the lines between Jo (the character) and Alcott (the author), who indeed never married in real life and used her own childhood as semi-autobiographical inspiration for her book.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The result requires Gerwig setting up Little Women as a sort of frame story, book-ended by Jo negotiating with her publisher, first over a short story and later over the novel Little Women itself. This is made entirely explicit; as Dana Stevens points out in her review at Slate, "[t]he leather-bound edition of Little Women that serves as the movie's opening title, its red leather cover stamped in gold with the name 'L.M. Alcott,' reappears in identical form at the end — all except for the name, which has become 'J.M. March.'"

Presenting a story as having been written by one of its fictional characters was actually a common 19th-century metafictional literary device used by the likes of Dickens and Swift, although, interestingly, not by Alcott. Over the years, though, the device has become an uninspired crutch for framing a story: Bilbo Baggins, returning from his incredible journey in The Hobbit, is suddenly possessed to write his story down despite basically not having shown any inclinations prior. Film directors in particular seem unable to resist the trope: In David Fincher's Zodiac, the cartoonist Robert Graysmith decides to write true crime despite it never having been suggested previously in the movie that he was a writer. Maybe most inexplicably of all, in Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway — a bond salesman in Fitzgerald's original — is inspired to pen ... The Great Gatsby?

The difference with Gerwig's creative liberties, then, is that she makes Jo's craft the heart of the movie rather than a mere narrative shortcut. Instead of being a preternaturally gifted writer, we see Jo put in the work, from stretching her cramped, ink-stained fingers to her rush to put pen to paper when seized by inspiration. In one montage, she obsesses over her novel's structure, laying out pages to dry and staring at the result. Importantly, we see the hardships of her work too, including the gutting loss of her book-in-progress (due to a fit of rage by her sister Amy; today it might be forgetting to hit "save" before a computer crash). When arguing with Bhaer, she also mentions her numerous rejections in the pursuit of her dream of making a living through her writing. Gerwig's movie is a bildungsroman, certainly, but maybe even more so it is a kind of visual craft essay, illustrating that writing isn't something you're born with, or suddenly possessed by, but have to struggle through long years of hard work to improve.

Still, there is Jo's great compromise at the end of the film. The publisher wants her protagonist married off; Jo eventually agrees. What follows is Jo's marriage to the professor — at least he is marginally less odious in her version than in Alcott's — complete with a tonally odd, climactic rush to the train station to stop him from leaving for California. But rather than show Jo's wedding, as would otherwise be natural for a story that revolved around the central tension of who does she end up with?, we see a beautiful montage of the bookbinding process, complete with a shot of Jo (Alcott?) looking, with maternal love and affection, at her newborn novel. It's so striking a redirection of narrative focus that many have wondered if Jo didn't get married to Bhaer at all in Gerwig's version.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The younger version of me, the one who was crushed all those years ago by Jo's decision to marry Bhaer, is delighted by this ambiguity. Still, I've watched enough Hallmark movies in the past few days to appreciate that what is shown on screen — that Jo gets both the career and the man — is still radical in this day and age, too. What's unchanged by either reading of the ending is that while the "book within a movie" trope might be an old and often unrealistic cliche, Gerwig's Little Women makes Jo's novel more than just a book spontaneously pulled out of the ether for a convenient conclusion. When Jo passes her hands over those small, slightly-crooked letters on the cover of her novel at the end of the movie, it doesn't feel familiar. It feels, wonderfully, like something brand new.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal