Jack Welch's legacy looks very different than it did 20 years ago

What we ultimately learned from the legendary CEO

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

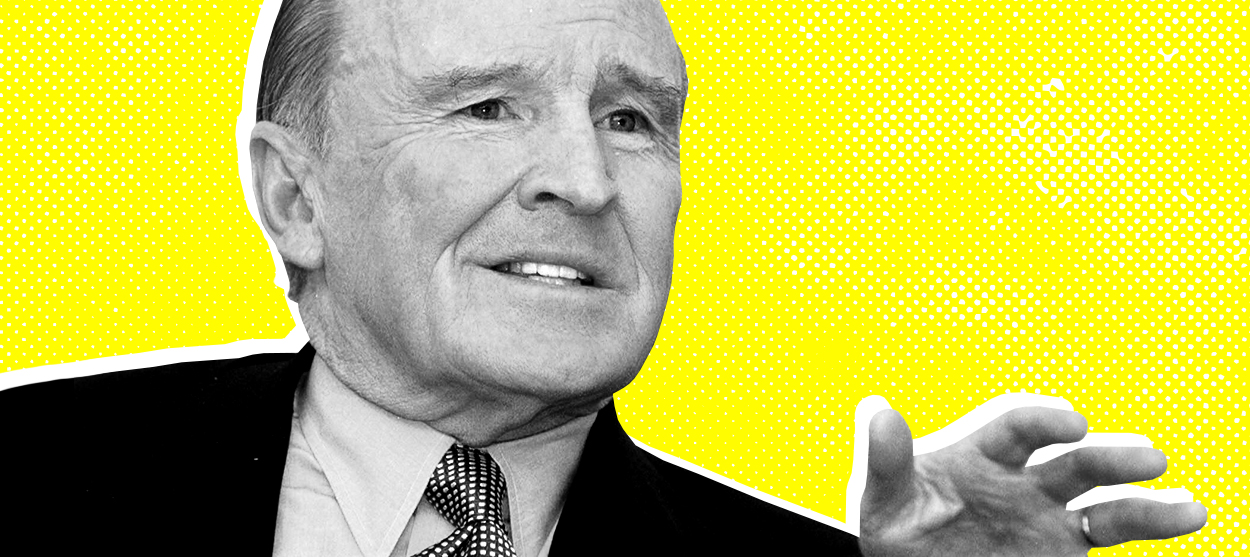

Jack Welch, the CEO who ruled General Electric from 1981 to 2001, died on Sunday.

Upon his retirement, almost 20 years ago, Welch was a legend — hailed as a "white-collar revolutionary" by The New York Times, and named "Manager of the Century" by Fortune — for taking an already famous manufacturing powerhouse and remaking it into a sprawling and wildly successful conglomerate with its hands in everything from health care to entertainment to big finance.

Upon Welch's death this past weekend, however, GE was a decimated shadow of its former self. And Welch's own legacy, to put it bluntly, lies in ashes: A warning for others of the dangers in 1980s-style Wall Street financialization, and of an overwhelming focus on shareholder value above all else.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Welch's rise to become GE's chief executive was certainly old school. He was born in Massachusetts in 1935, to a railroad conductor father and a stay-at-home mother. He got his doctorate in chemical engineering in 1960, and joined GE's plastics division that same year. He then rocketed up through the company's internal ranks, becoming vice president in 1972, vice chairman of the board in 1979, and then finally both CEO and chairman in 1981.

But when it came to management style, Welch was something else entirely; he earned both praise and criticism for an approach that could be characterized as either efficient or brutal, a hard-charging strategy that came off as abrasive while also profoundly remaking the company. Welch cut through layers of bureaucracy and personally oversaw a whole host of corporate governance decisions, while instituting a new performance assessment and ranking system that showered rewards on the top 20 percent of management, tried to help the next 70 percent become more like the top 20 percent, and then culled the bottom 10 percent annually.

Welch brought that same Darwinian sensibility to dealing with GE's various business arms, issuing a famous edict to "fix, sell, or close." During his first five years as CEO, Welch reduced GE's employee population down from 411,000 to 299,000, in a merciless effort to cut out any part of the company that didn't meet his exacting standards for creating value. That garnered him the nickname "Neutron Jack," after the bombs that kill human populations off with massive radiation bursts but leave more buildings and infrastructure standing.

There's plenty one could say to criticize this sort of management style, and its consequences for the human beings who actually make a company run. But how Welch defined "creating value" is arguably where his most consequential and tragic error lies.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Years after his retirement, in 2009, Welch told the Financial Times that shareholder value — the corporate governance philosophy that a company should focus on maximizing returns to its shareholders to exclusion of all else — was "the dumbest idea in the world." But while Welch ran GE, you could find few better exemplars of putting "shareholder value" into practice: It wasn't just that Welch laid off over 100,000 workers; he closed huge swaths of GE's domestic factory operations — up to and including the company's famed light bulb manufacturing — and sent them overseas where labor was cheaper. "If I had my way, I'd put every GE plant on a barge," he once declared.

To further juice General Electric's stock market value and its returns to the ownership class, Welch took the billions he saved from all those closures and layoffs and embarked on a sweeping quest to buy up companies in sectors and industries far beyond GE's original core competencies in manufacturing, engineering and electronics. The company became a massive conglomerate, with major stakes in health insurance, pharmaceuticals, finance, entertainment, and more. By the time Welch retired in 2001, GE's annual revenue flow had increased five times over, and its stock market value had exploded from $14 billion to $410 billion.

Then it all fell apart.

The first blow came almost immediately with the stock bust of 2001, which massively reduced GE's market value. Of course, it massively reduced everyone else's market value too. Then came the 2008 financial crisis. Welch's most fateful move was arguably the creation of GE Capital, a mammoth $500 billion financial operation, entangled deeply in credit cards, insurance, subprime mortgages, shadow banking, and more. When the financial markets imploded, GE Capital went with them, and was ultimately only saved by a $12 billion injection from private investors and another $139 billion federal bailout. Several years later, it became obvious the entire long-term health care insurance industry had badly underestimated its future costs — and GE Capital had, of course, bought a major stake in the sector, leading to another multi-billion dollar hit.

Granted, GE was not helped along by other decisions made by Welch's successors; the company has churned through several CEOs since. But it's undeniable that Welch's governance and strategy laid the shaky foundations of "the house that Jack built," even if the blows that ultimately decimated the structure didn't come until after he left. GE's been slowly carving off its various arms — in finance, health care, energy, biopharmaceuticals — and selling them for spare parts; it's been kicked off the Dow Jones; its business model continues to struggle.

Focusing on shareholder value and stock market capitalization ultimately turns a company into an abstraction, its life sustained by financial flows that are less and less connected to the underlying fundamentals of the company — its workers, its resources, its infrastructure, the real needs it provides to the people it serves. When the good times end and the money dries up, what's left of the company may not be able to stand on its own.

After retiring, Welch became a consultant and an author and a TV pundit (and occasional conspiracy theorist, as he accused the Obama administration in 2012 of juicing its employment stats to win re-election) while the worlds of business and finance — not to mention the rest of the country — have been left to reckon with the aftermath of the corporate philosophy Welch did so much to champion and exemplify.

When Welch retired in 2001, The New York Times' editors wrote that "his legacy is not only a changed G.E., but a changed American corporate ethos, one that prizes nimbleness, speed, and regeneration over older ideals like stability, loyalty, and permanence." If nothing else, Welch left us with a very concrete demonstration of where that particular set of priorities ultimately takes you.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.