How pandemics change society

History can tell us a lot about the ways coronavirus might transform how we live

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Black Death, the Spanish Flu, and other widespread disease outbreaks have transformed how people live. Here's everything you need to know:

Will Covid-19 change the world?

Yes, if it's similar to the pandemics of the past. Plagues and viral contagions have regularly blighted the course of human civilization, killing millions of people and wreaking economic devastation. But as each pandemic receded, it left cultural, political, and social changes that lasted far beyond the disease itself. The great outbreaks of history — including the Athenian Plague, the Black Death, and the Spanish Flu — transformed health care, economics, religion, the way we socialize, and the way we work. "Things are never the same after a pandemic as they were before," said Dr. Liam Fox, a former U.K. defense secretary who's studied these outbreaks for a forthcoming book. "The current outbreak will be no exception."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When was the first pandemic?

The earliest on record occurred during the Peloponnesian War in 430 B.C. Now believed to have been a form of typhoid fever, that particular "plague" passed through Libya, Ethiopia, and Egypt before striking the city of Athens, then under siege by Sparta. Thucydides chronicled Athens' misery in lucid detail, writing of sufferers' lesions, red skin, and bloody throats and tongues, and the apocalyptic scenes within the city's walls as "dying men lay tumbling one upon another in the streets." The plague would ultimately play a large part in Athens' eventual defeat by Sparta, and the sense of despair led to a surge in licentiousness among the population. In many pandemics across the ages, people have taken refuge in sex and drinking, as well as in increased religiosity. The Justinian Plague of A.D. 541 fueled the rapid rise of Christianity throughout the Mediterranean.

What caused the Justinian Plague?

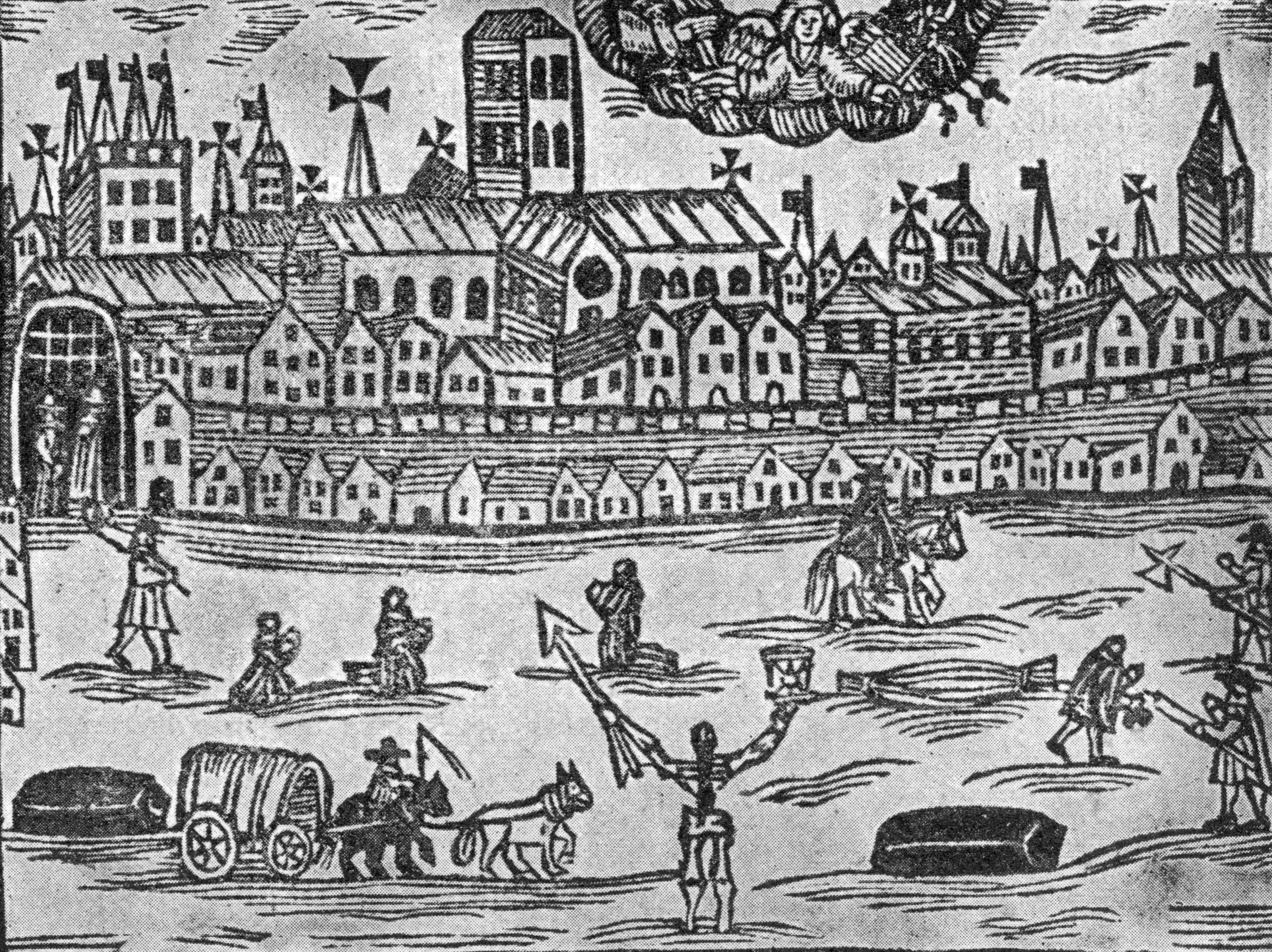

Yersinia pestis, a bacterium spread by fleas on rodents — the same culprit behind one of the worst pandemics in human history: the Black Death. Arriving in Sicily on a trading ship in 1347, the Black Death eventually spread throughout Europe and wiped out about 200 million people — up to 60 percent of the global population. People died horribly, afflicted with terrible aches, vomiting, and pus-and-blood-filled "buboes" in their armpits and groins. As the Black Death swept through Europe, it did, however, force authorities to institute health measures that remain in place today. Fourteenth-century Venice ordered mandated isolation periods, named quaranta giorni — or "quarantine" in English — to signify the 40 days of isolation imposed on incoming ships. Routine medical inspections became customary, and hospitals were built throughout Europe to treat the sick.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What other impact did it have?

The Black Death's biggest socioeconomic legacy was its role in ending feudalism. Feudalism was a medieval system that empowered wealthy nobles to grant the use of their land to peasants in exchange for their labor — with rent, wages, and other terms determined by the lords. By wiping out a huge swath of the working population, the Black Death created a labor shortage that gave peasants the leverage to negotiate new working terms — effectively bringing about the end of serfdom and paving the way for modern capitalism.

What about other epidemics?

In 1802, an outbreak of yellow fever in the French colony of St. Domingue (now Haiti) triggered a chain of events that led to the vast expansion of the United States. The epidemic, caused by a virus transmitted by mosquitoes, killed an estimated 50,000 French troops trying to control Haiti, forcing France to withdraw. The loss of this key Caribbean outpost was so economically damaging to France that Napoleon sold off 828,000 square miles of French territory in North America, extending from New Orleans to Canada, to President Thomas Jefferson for a mere $15 million: the Louisiana Purchase. That may have been the most consequential outbreak in the history of the Americas until the Spanish Flu erupted in 1918.

What was the Spanish Flu?

It was a virulent strain of H1N1 influenza that may have actually originated on a Kansas poultry farm. One of its first victims was a U.S. soldier stationed in Kansas. Unlike the bacterial plagues of the past, the Spanish Flu was a virus, which became more deadly when it picked up some genetic material from a virus infecting birds. Spreading like wildfire among soldiers in the trenches of France and Belgium and then around the globe, the pandemic "influenced the course of the First World War and, arguably, contributed to the Second," says science journalist Laura Spinney, author of a book on the Spanish Flu. The virus killed approximately 50 million worldwide, including 675,000 Americans. Among those struck down were a number of American delegates to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 — many of whom were opposed to making German reparations a condition of the Treaty of Versailles. With the Americans missing, delegates approved the punishing reparations, and the humiliation Germans felt was a key contributor to Hitler's rise. Like the Black Death, the Spanish Flu revolutionized public health, spawning the new fields of epidemiology and virology. It led several Western European countries to adopt universal health-care systems that are still in operation. "The Spanish Flu," says Spinney, "resculpted human populations."

COVID-19's possible legacy

The coronavirus has already had a huge and potentially enduring impact on everyday life. Our work and social lives have gone virtual, with even G-7 leaders conducting their meetings via videoconferencing. Movie studios, gyms, musicians, and karaoke bars are streaming their content straight into our homes. The outbreak has revived impassioned debates about the U.S. health-care system, possibly offering a boon for those in favor of universal coverage. And it may have an even wider geopolitical legacy. The Spanish Flu and the economic depression that followed led to a wave of nationalism, authoritarianism, and another world war. Spinney says the same could happen in the aftermath of the coronavirus, reversing the tide of globalization and fueling xenophobia at a time when countries should be united against a common viral enemy. "We've forgotten a lot of the lessons that we learned after the Spanish Flu and other pandemics," Spinney says. "We may be about to learn them again."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.