The troubling trend toward collectivized punishment

The notion that anyone would be punished for someone else's crime is repulsive. But in the turmoil of police violence against peaceful protesters and rioters' destruction of homes and businesses, it's gaining new life.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Among the horrors of North Korea's prison camps is the regime's "three generations rule," which dictates that prisoners, their children, and their grandchildren — even if yet unborn — will live out their days within camp confines. Whole families are brutalized for one member's alleged crime.

We recoil from this, and rightly so. It is evil. It is also an exceptionally miserable example of collective punishment, a practice not eliminated but certainly dramatically curtailed in the modern West by Christian anthropology and Enlightenment individualism. Our ancestors could make sense of punishing entire families or towns or peoples for one member's wrongdoing, whether real or imagined. Now the notion that I would be punished for someone else's crime is repulsive.

But perhaps it is not repulsive enough. In the last week's turmoil of police violence against peaceful protesters and rioters' destruction of homes and businesses, this mode of retribution seems to have gained new life. It is a terrible regression.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Our country is no stranger to collective punishment, for all the stubborn individualism of our culture and Constitution. The Boston Tea Party, which has been much invoked of late in sympathy for rioting, was followed by the "Intolerable Acts," laws intended to punish the entire colony of Massachusetts for that initial rebellion. During the Civil War, Union General William Sherman was notorious for ordering his men to "enforce a devastation more or less relentless" in proportion to the harassment Union troops received in each locale. World War II internment of Japanese Americans was a type of collective punishment, as were the U.S. nuclear strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

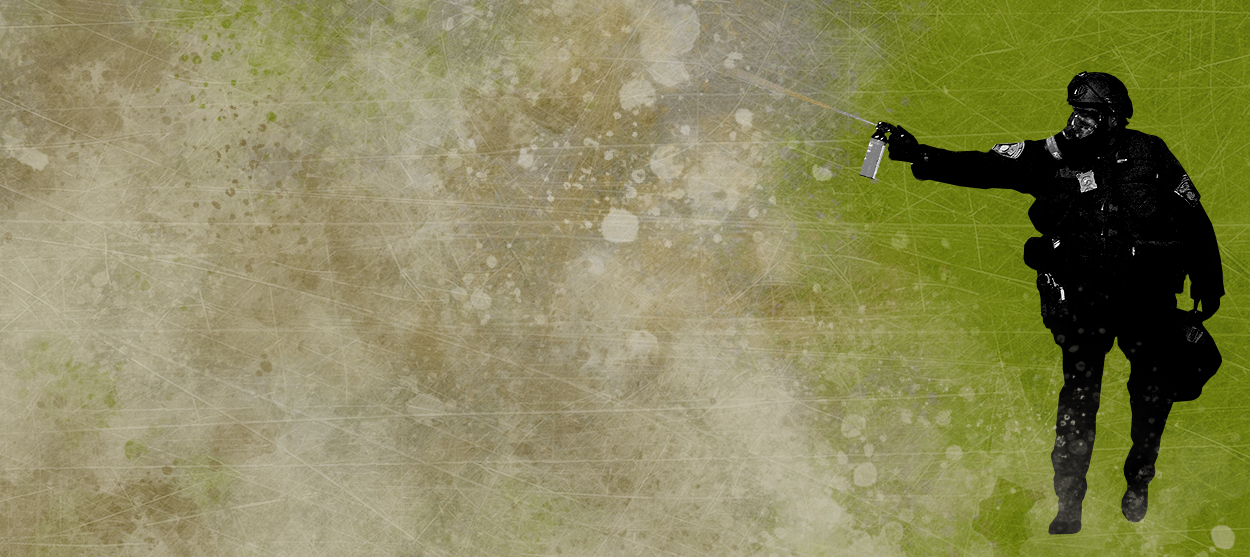

Black Americans especially have known collective punishment all too well, from the state, enslavement, and the lynch mob alike. After abolition, many states passed "black code" laws and adopted policing practices to replicate slavery's control and exploitation of the black population insofar as the new legal environment permitted. Police brutality against nonviolent protesters during the Civil Rights era and up through this very week continues this disgraceful tradition. Collective punishment is far from the only wrong here, but collective punishment it is. Whole crowds are being punished for the violence of a few.

And about that few: They're engaging in collective punishment, too, and those defending random destruction are endorsing it. (Some people rioting and looting are merely opportunists or looking to blow off steam; others are there to cause chaos in pursuit of goals unconnected to policing reform. I am speaking of those rioting because they are angry at the police.)

It is one thing to burn, say, a Minneapolis police precinct. It was a Minneapolis police officer, after all, who choked the life out of George Floyd. Set aside, for the sake of discussion, your views on the ethics, strategy, and consequences of burning the precinct. Whatever we make of all that, burning it is a punishment targeted to the party directly responsible for Floyd's death.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The same cannot be said of the hundreds of businesses damaged in the Twin Cities over the last week. Here is what my pharmacy looks like now:

Or scroll through the pictures of Bolé, a nearby immigrant-owned Ethiopian restaurant that also burned. Perhaps, still setting aside other considerations, you can make a case that Target — which reportedly donated $300,000 to the Minneapolis Police Department for surveillance cameras in 2004 — has a degree of responsibility for area police misconduct. But the pharmacy? Or Bolé? Or any of the other dozens of businesses that sustained smaller damages? No.

Our neighborhood, at least, will get along okay while looted stores are closed. Next to the Target, there's another grocery store which has already re-opened; we have other pharmacies; and numerous Asian markets are running, too. But in the Minneapolis neighborhood surrounding the burned precinct, rioters created a food desert. Many in the community had to rely on donations to get through the weekend because public transit is still suspended and everything in walking distance was destroyed or closed. They are suffering for a crime they did not commit.

Only under the irrationally expansive notion of guilt assumed by programs of collective punishment are these victims of the past week's ruin getting what they deserve. Those who defend this indiscriminate destruction should be clear on what they're defending — and clear that they are mirroring one aspect of the systemic injustice they rightly deplore.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day