When U.S. history became a little less black and white

Travel back in time with the country's first color photographs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Think back to the iconic scene in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy wakes up and realizes she isn't in Kansas anymore. The prairie's monochromatic hues have been abruptly replaced by poppy reds, electric blues, and — of course — golden-brick yellows.

Developing the first colored photographs was a little bit like that. Before people had stared stoically out from somber street scenes; now it was as if they could leap right out of the image.

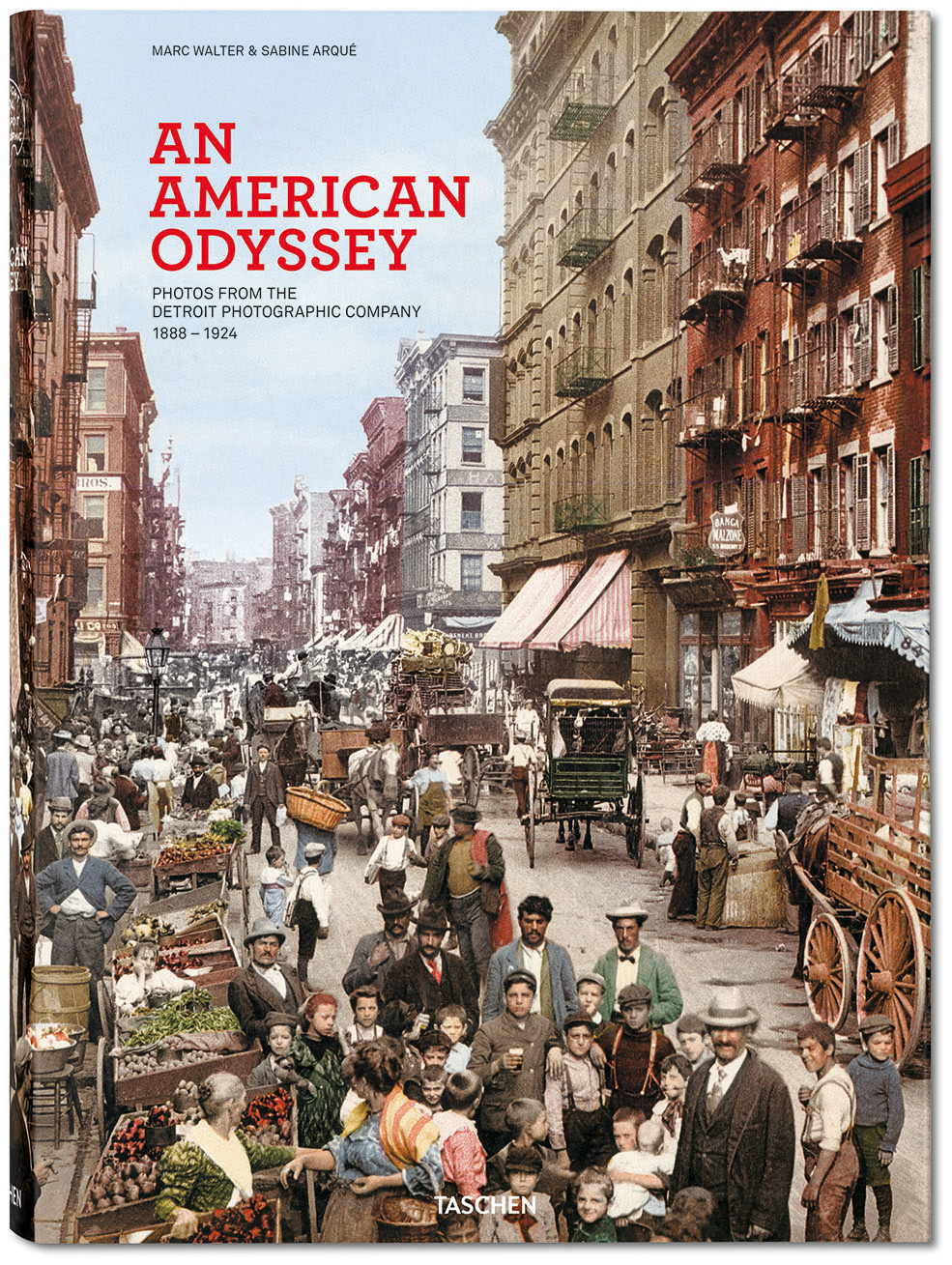

Collector Marc Walter has teamed up with publisher Taschen to document that moment in a new book, An American Odyssey, which features hundreds of images from the period.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The United States cannot claim credit for developing the technique that turned photos technicolor. That honor belongs to Switzerland, where workers pioneered the process in the mid-1890s. They used a monochromatic glass negative, and merged lithography — a flat surface is treated to repel the ink except where it is required for printing — and photography to create photochrom prints.

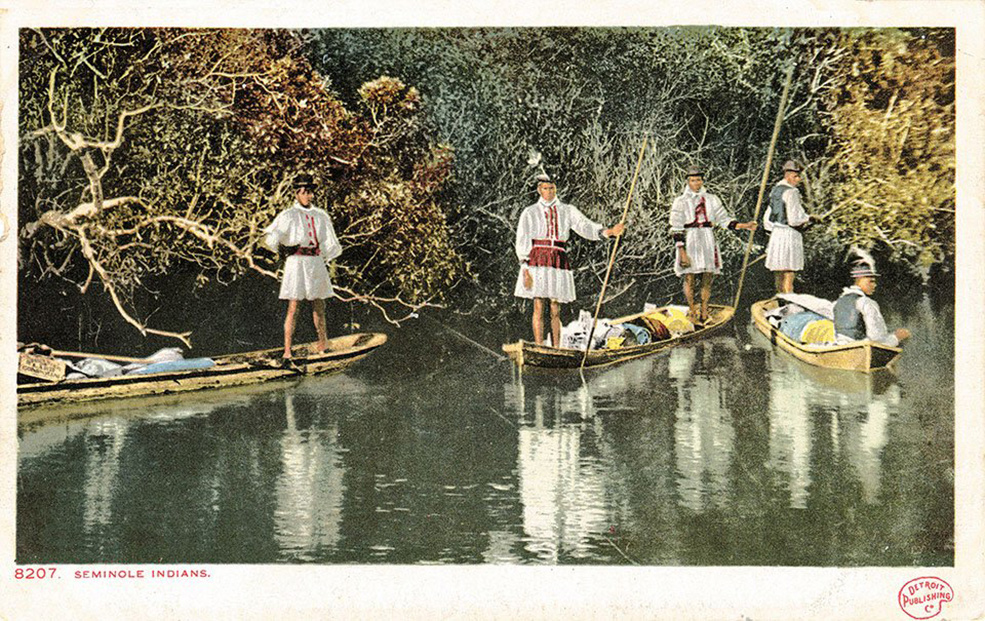

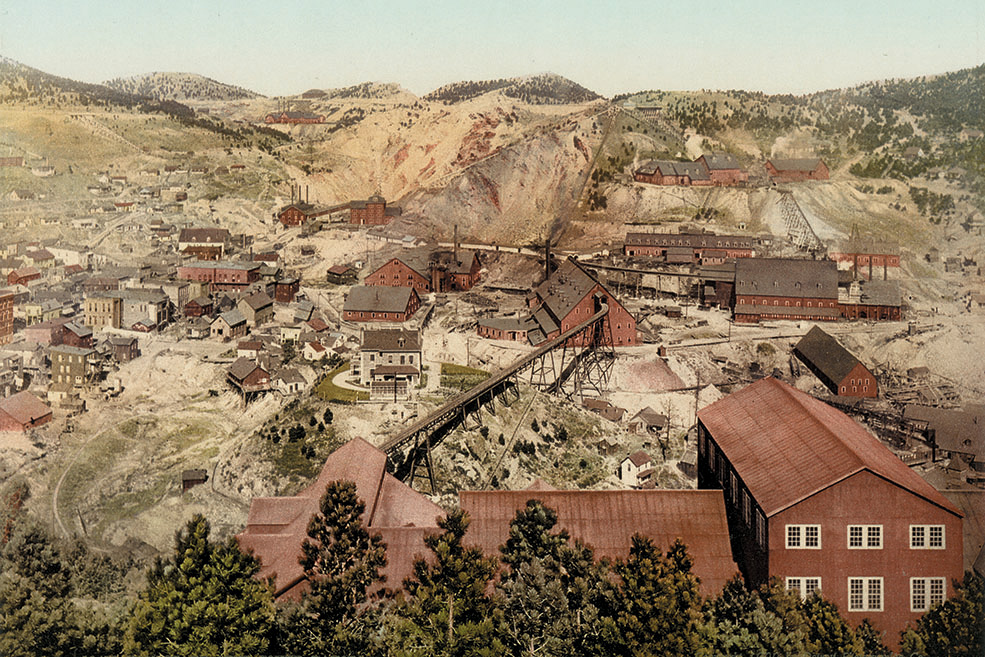

The process produced multiple prints of a single image, spawning the commercial market for color-photo product. Sensing a surefire moneymaker, the Detroit Photochrom Company (DPC) opened a factory, licensed the technique, and hired William Henry Jackson, a Civil War veteran and well-traveled photographer who had already made his mark capturing people and landscapes. The hire gave DPC access to more than 10,000 of Jackson's glass negatives.

Suddenly, Americans could purchase richly colored images of places such as Little Italy and the Grand Canyon, which had been depicted only in black and white before.

In 1898, when Congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act, which allowed private companies to publish postcards, DPC was perfectly prepared to churn out its colored images as souvenirs. Between 1888 and 1924, experts estimate that DPC made over seven million prints.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The lights went out in 1932, after DPC found itself unable to keep up with a newly crowded industry. The recession set off by World War I didn't help the company either. The collection scattered into private holdings across the nation, seemingly forgotten as colored images turned from novelty to ubiquity.

But Walter, who has gathered one of the world’s largest sets of photochroms, certainly didn't forget. An American Odyssey features more than 600 pages of images from The Walter Collection.

It's like entering Oz all over again.

Loren Talbot is the photo editor for The Week magazine. She has previously worked for Stuff, Maxim, Blender, and Us magazine, as well as for the Sweet Genius production company. She is a graduate of both Marlboro College and Pratt Institute. Her part-time job is adventurer.