Inside Sao Paulo's 'Crackland'

A social experiment in Brazil's financial center provided crack addicts with jobs, beds, and the freedom to use drugs openly

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

(Almudena Toral)Luz, the downtown historic district of the Brazilian city, should be a cultural gem — packed as it is with the kind of baroque and neoclassical buildings seen largely in Europe.But over the past several decades, this once-vibrant neighborhood has been consumed by Brazil's crack epidemic. Ragged, sickly bodies laze on the streets amid garbage, makeshift shelters, and shopping carts filled with soiled belongings. People light up openly, day or night. Some wear their pipes around their necks like a talisman.Cocaine rocks come cheap and easy here, with the next hit less than a few dollars away. Hundreds of homeless have set up camp on a few blocks at the district's center, but thousands more pulse in and out of the area regularly seeking that same brief, soaring high.Welcome to Cracolândia.

(Almudena Toral)Similar "Cracklands" exist in cities across Brazil, which is home to some one million crack users thanks to its shared borders with Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia — three of the world's largest cocaine producers.As the oldest and largest of these crack havens, Sao Paulo's Crackland has been the target of local and state-level rehabilitation campaigns, many of which have involved aggressive police enforcement and involuntary treatment in facilities that function more like prisons than health centers.In January 2014, the city tried a new, progressive approach to dealing with addicts. The program, called De Braços Abertos ("With Open Arms"), and introduced by then-Mayor Fernando Haddad, offered crack users housing, medical care, food, and even part-time custodial employment. Those who worked were paid a small wage, which they were free to use on anything they wanted — including drugs.Instead of being plagued by random arrests and forced clearings, Crackland's busiest and most dangerous block was monitored 24/7 by police officers ordered to treat addicts as "sick people" instead of criminals. The quarter also teemed with a support staff of emergency health personnel, social workers, and ministers.

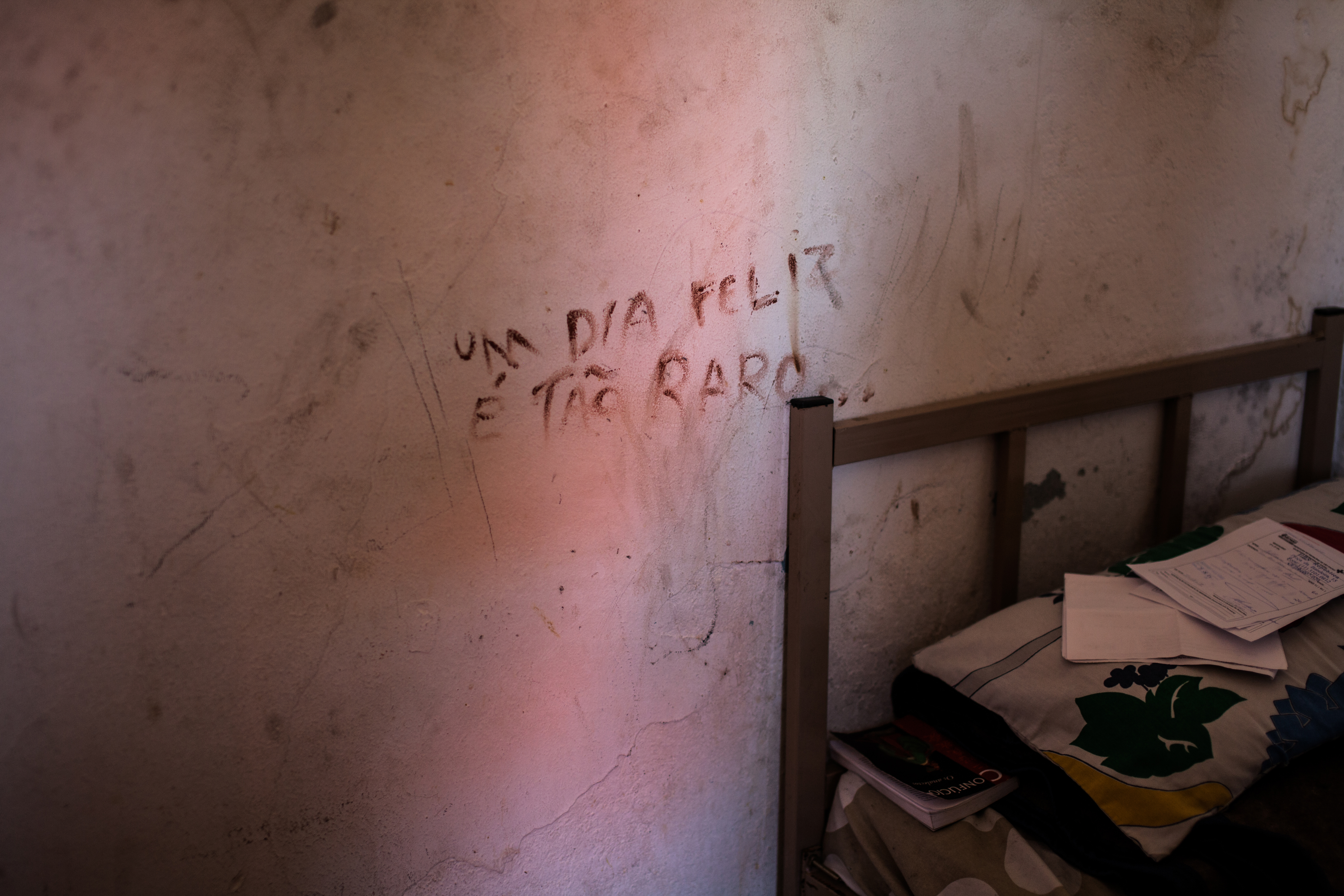

(Almudena Toral)Toral met a range of users — from those taking the De Bracos resources with no intentions of quitting, to women who desperately wanted to get off drugs and needed the shelter, promise of safety, and aid.One woman Toral spoke to was pregnant with her fifth child — the other four had been kidnapped, abandoned, or had abandoned her. Now she had stopped using in the hopes of keeping this baby, but she depended on the program's medical services to get her through her pregnancy."She definitely saw it like it changed her life, being able to access housing and being able to have a bed to sleep in and being able to choose who she slept with or who she didn't," Toral said. "Maybe it sounds silly, but for some of these women, that wasn't a choice before. It was definitely a pure source of hope for her."

(Almudena Toral)By many reports, the program was a success. One study found that almost two-thirds of the De Bracos Abertos' participants reduced their drug intake within one year.But with the election of Sao Paulo's Mayor Joao Doria, who took office in January 2017, De Bracos Abertos' time was up. Doria ran on a campaign to clean up Sao Paulo, which included the promise to scale down the program. In May 2017, bulldozers and hundreds of military troops — armed with gas grenades, rubber bullets, and raid dogs — descended on Crackland, dismantling it entirely.Doria called the operation a raid to arrest traffickers and seize drugs and guns. But his bold move won little support from the neighborhood locals or the displaced addicts who said they received no advanced warning. Meanwhile, addicts find space where they can, in nearby parks or around the city, but are often raided by police and sent scattering again. The original Crackland may be gone, but the city's crack epidemic is far from solved."Nothing there in Crackland was black and white," Toral said. "It's a place full of contradictions. There was a lot of sadness and a lot of anger, but there was also a lot of joy and hope. … When you get to meet individual people and individual stories, it's remarkable how these contradictions play in each one of them. So many of them had normal lives before and families before falling into drug addiction. They were mothers and daughters."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kelly Gonsalves is a sex and culture writer exploring love, lust, identity, and feminism. Her work has appeared at Bustle, Cosmopolitan, Marie Claire, and more, and she previously worked as an associate editor for The Week. She's obsessed with badass ladies doing badass things, wellness movements, and very bad rom-coms.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day