The boring explanation for what went wrong with our pandemic response

COVID, Chipotle, and the risks of narrow expertise

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In October 2015, an e. coli outbreak struck the Pacific Northwest. It didn't take long to identify a number of Chipotle Mexican Grills as the culprits. Once the company knew the outbreak had originated in its restaurants, Chipotle shuttered more than 40 stores in the region attempting to contain it.

That might have seemed like the end of the affair, but it was only the beginning. The subsequent saga is now largely forgotten, but it's worth re-examining for its illuminating parallels with the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the two together points to something about the behavior of large institutions and narrowly trained experts in moments of crisis: Under pressure, tasked with a single goal, and subject to intense public scrutiny, they have to do something. Unfortunately, the result is often as much about panic and performance as it is about expertise.

Some of the similarities between these two crises are superficial. For example, both the original e. coli outbreak and the first confirmed COVID-19 case took place in Washington State, and in each case the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention drew criticism for its initial announcement of the problem. But other similarities, which I've noticed thanks to this 2016 deep dive, "Chipotle Eats Itself," by Austin Carr for Fast Company, are more instructive for exploring the risks of narrow expertise.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Both cases saw early confusion about the source of the danger. Speculation abounded about the origin of the novel coronavirus last year, and that question remains significantly unanswered. Chipotle stores were told to urgently throw away all cilantro — then informed a couple of hours later that was a false alarm. In fact, it was all false alarms: Though Chipotle overhauled its sourcing and preparation methods, it did so without ever actually identifying the ingredient that caused the first outbreak. These knowledge gaps fueled conspiracy theories about COVID and Chipotle alike, with the Chinese military and Monsanto or some other shadowy "Big Food" actor cast as the crises' respective villains.

Testing debacles are also a commonality. Test shortages were a major concern in the first six months of COVID-19, and our home testing options still lag behind those of other nations, like the United Kingdom. At Chipotle, there was confusion over what was known as "high resolution testing," a method of identifying whether food may harbor dangerous pathogens. Chipotle chose the less informative of two testing options, and one food safety expert retained by the company believed neither of its co-CEOs understood the difference between the two tests — or even what high-resolution testing really was.

More important than these, however, were the economic and personal effects as each crisis response got underway. Despite there being no evidence that locally produced food from small farms had anything to do with any of the outbreaks, Chipotle cut purchases from its vaunted small farm partners to centralize food sourcing so any future outbreaks could be more easily traced. In the pandemic, too, small business bore the brunt of the pain. Walmart earned the "essential" designation while many small stores were forced to close entirely.

Chipotle also reacted by instituting draconian food-safety checklists. Company leadership browbeat restaurant crews over compliance, tanking morale and, with it, enthusiasm for needed safety measures. The new rules allowed little room for individual judgment, discretion, or risk assessment, seeing these not as vital analytical tools but as evidence of insufficient commitment to safety. Low-level retail and food service employees have likewise been given enormous responsibility and very little leeway for prudential judgment in dealing with COVID-19.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The question is why expert-led crisis responses turn out this way. Why does our approach to safety favor bigness, standardization, and centralization? Why are top-down directives so often rigid, even when they're based on little to no certain knowledge of the crisis at hand?

One theory of the pandemic public health response, common in social and religious conservative commentary on the pandemic, is that physical health has become our society's consuming priority. "Because we value health above all, we subordinate the spiritual to the temporal," Matthew Schmitz wrote in First Things in March of 2020. "Important as health is, things begin to look strange when it is valued above all else." Schmitz argued that the hasty sorting of businesses into essential and non-essential categories was not a high-pressure, technocratic judgment call but a metaphysical argument of sorts.

That theory got a big boost when, in the wake of protests over the murder of George Floyd last summer, over 1,000 public health experts argued that mass protests during the pandemic were justifiable because racism was also an urgent public health issue. And around the same time, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio insisted to a Jewish media outlet that the struggle against racism was "not the same question as the understandably aggrieved store owner or the devout religious person who wants to go back to services." The protests would be permitted, he said, while much smaller religious gatherings would not.

Perhaps, as Schmitz and other conservatives charged, these statements showed our society in general and public health experts in particular are lacking in spirituality or a sense of the transcendent. Perhaps the rigid, large-scale pandemic rules were the logical result of belief in nothing beyond this physical life.

But does that really add up? The Chipotle comparision suggests another explanation. There, the stakes were far lower and less contentious — no one died from Chipotle's contaminated food, and it's hard to read metaphysical arguments into burritos. Yet in both crises, leaders with narrow expertise, operating under intense pressure, focused on solving the big problem in their own wheelhouse to the detriment of everything else. Panicked and feeling a need to perform, they laid down the law in the one area they knew well, unaware of or unable to adjust for the negative externalities that law would have.

And then they went a little further than may have been immediately necessary, too, using the moment's fear and uncertainty to push through changes that wouldn't have been acceptable in normal times. At Chipotle, many of the post-outbreak food-safety measures remain in place to this day, a "new normal" for a chain that once eschewed central preparation and embraced fresh, raw ingredients. What pandemic safety measures will stay in place after COVID-19 becomes endemic remains to be seen.

Jim Marsden, a Kansas State University meat scientist and Chipotle's top food safety expert, is paraphrased in the Fast Company story as saying that "not knowing the exact cause of the e. coli outbreak meant the company had a chance to fix everything." To conservative ears, that might sound eerily like left-wing social engineering — "Never let a crisis go to waste" — but in this context, of course, it's nothing of the sort. It's just narrow expertise at work.

This explanation means the public health response to the pandemic, though obviously imperfect, was not about spiritual poverty or political radicalism. And it means the answer to inflexible, sweeping pronouncements of narrow expertise is not the abandonment of liberalism or some even more sweeping political change. It's boring, technocratic stuff.

It might include reforming and broadening the education and training that public health and safety experts receive. It might mean making their curriculum more interdisciplinary, teaching them to think and talk about trade-offs and risk assessments in ways that don't minimize the crisis at hand but illuminate different approaches and allow different disciplines to work together.

Throughout the last year and a half, public health experts have been carrying out their mandate, and they've generally done about as well as could be expected in an incredibly difficult time. But maybe it's time to rethink that mandate itself. Maybe it's time to foster a broader — and therefore more humane — style of expertise.

Addison Del Mastro writes on urbanism and cultural history. Find him on Substack (The Deleted Scenes) and Twitter (@ad_mastro).

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

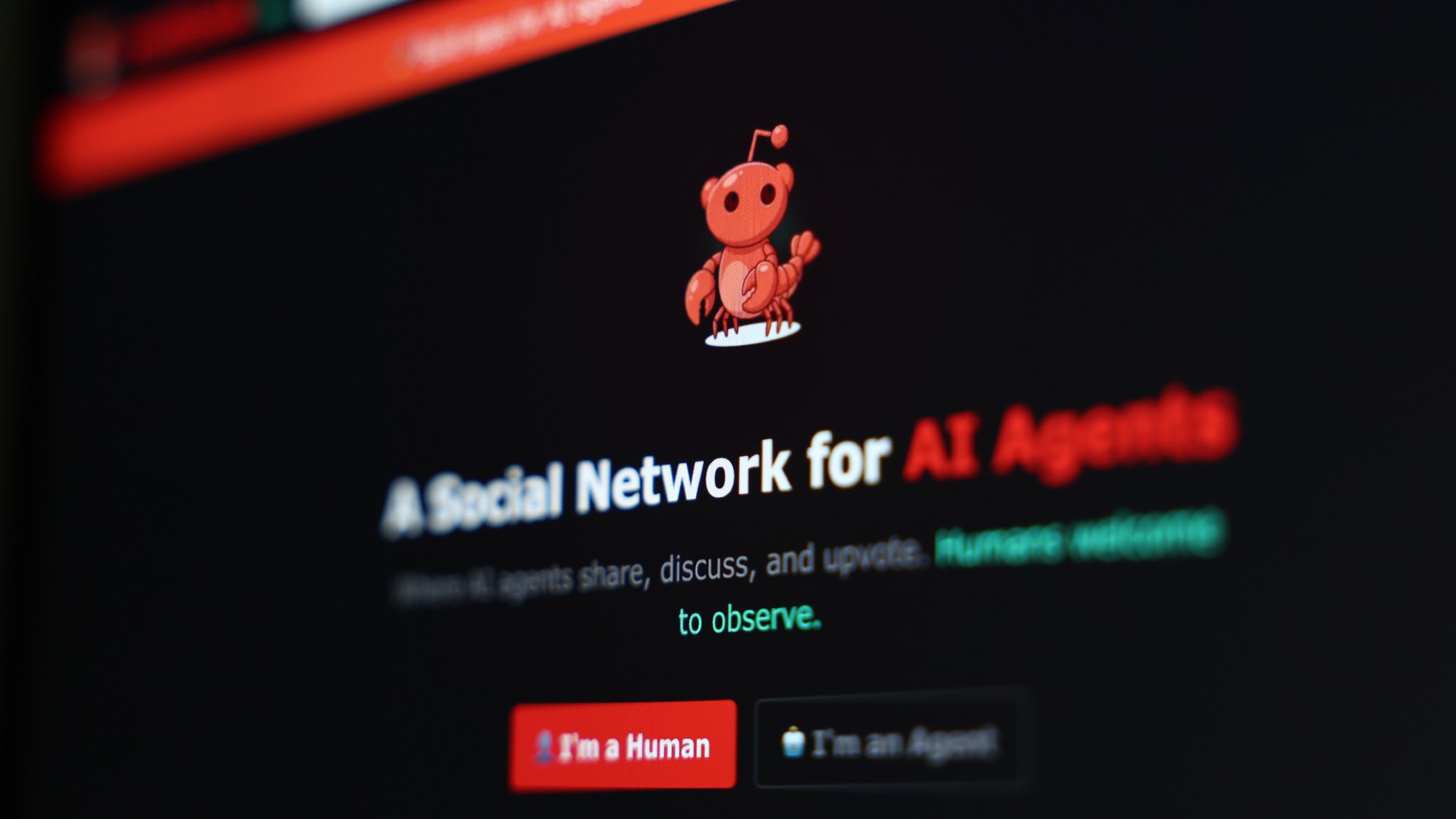

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg