Millennials are becoming financial Neanderthals

And that might be unkind to Neanderthals

All age groups are investing less in stocks since the 2008 recession. But for millennials, the youngest group — who have most of their working lives left ahead of them, and can therefore afford to take the most risk — the fall has been particularly precipitous.

Just 27 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds reported owning shares in individual companies or as part of a fund, down from 33 percent in April 2008, according to the latest Gallup poll on the matter.

So what's different for millennials? Over at Bloomberg, Jeanna Smialek argues that they have become extremely risk averse due to the two financial crashes we have seen in our lifetimes: "As the oldest millennials approached college graduation in 2002, they witnessed a 78 percent plunge in the Nasdaq index as the bubble in technology shares burst. As they reached their mid-twenties in 2008, the Standard & Poor's 500 Index dropped 38.5 percent, the worst single-year performance since 1937. The gauge dropped 57 percent from October 2007 through March 2009."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But I don't think that's a great excuse. Millennials haven't just been exposed to two big financial crashes; they have also been exposed to some pretty big booms, such as the current great bounceback from the 2008 recession. I am a millennial. I was born in 1987, and even in my lifetime — the period during which we millennials were supposed to have been "scarred" — stocks have actually appreciated a lot, and are making all-time highs:

[YCharts/Standard & Poors]

Over the last 200 years stocks have vastly outperformed every other type of asset. In the long run, it is much smarter to give your investable money to productive businesses that produce a return than stash it in a bank account, or gamble on a depreciating asset like real estate, or speculate on a shiny but totally unproductive asset like gold. This is basic information available to everyone, not some deep secret available only to the elite.

Now, it's important to mention that millennial investment in stocks may be down as a whole because young people just don't have the money to invest. Wage growth has been relatively weak since the recession. And unemployment and underemployment is still high, and if you're unemployed you're not going to be able to invest even if you wanted to.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But actually, the data shows that even millennials who do have the money to invest are avoiding stocks. A UBS survey released earlier this year found affluent millennials hold 52 percent of their money in cash and 28 percent in stocks, compared with 23 percent and 46 percent for older people. So even affluent young people today are putting their money into bank accounts and securities that pay close to zero interest. That means getting a negative real return, as even 1 percent or 2 percent inflation is more than zero interest. That isn't building wealth. That's willfully destroying it.

As for stocks, 46 percent of millennials with more than $100,000 to invest say they will "never be comfortable in the stock market," one survey released in February found. And 52 percent of millennials said they are "not very confident" or "not at all confident" putting money in stocks for retirement, according to a February 2013 survey by Wells Fargo.

To someone who grew up in the shadow of the Great Depression — where stocks crashed in 1929, and didn't fully recover until 1951, this kind of behavior might be sort of rational. But to millennials who have seen decent stock market gains during their lifetime, it really isn't. It's willful ignorance. The nature of compound interest means that the earlier you start investing, the better, and the sooner you can retire.

Now, I'm not going to deny that during and after the crisis there wasn't something apocalyptic in the air. Financial panics are frightening, and the recovery has been slow and lackluster. But we're now almost six years past the crisis. Today, corporate profits are actually at record highs. And while the crisis resulted in a big stock market crash, the crisis wasn't about stocks, it was a crisis of subprime lending, shadow banking, and (arguably) high oil prices.

And yet it seems that the millennials are still acting like we're near the end of the world, the stock market was the problem in 2008, and sitting on cash is a smart thing to do even with interest rates near record lows.

This is totally boneheaded, and lots of people are going to wake up in 20 years when they're closer to retirement and regret it.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

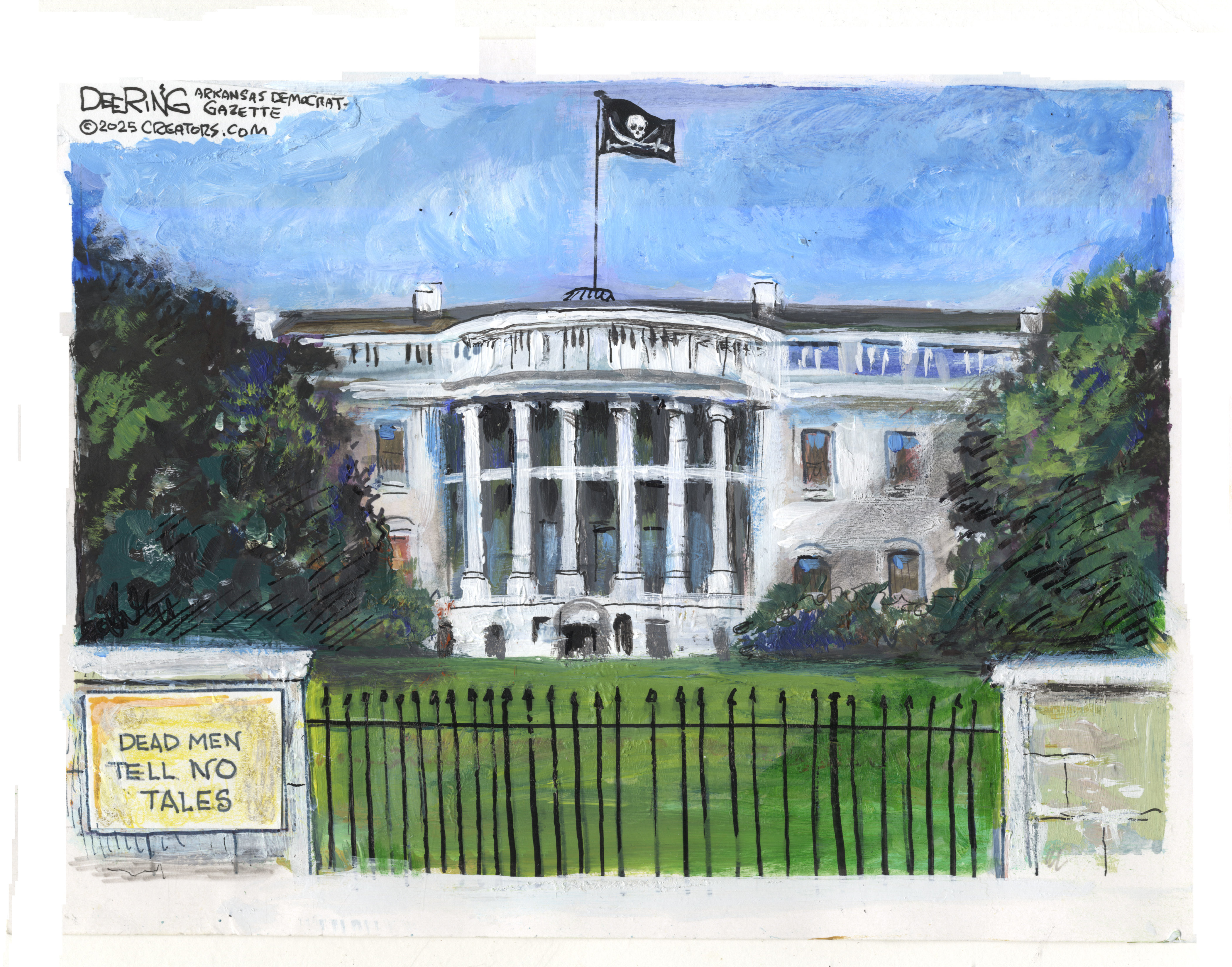

Political cartoons for December 14

Political cartoons for December 14Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a new White House flag, Venezuela negotiations, and more

-

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of Canada

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of CanadaThe Week Recommends ‘Mind-bending’ outpost for spotting animals – and the northern lights

-

Facial recognition: a revolution in policing

Facial recognition: a revolution in policingTalking Point All 43 police forces in England and Wales are set to be granted access, with those against calling for increasing safeguards on the technology